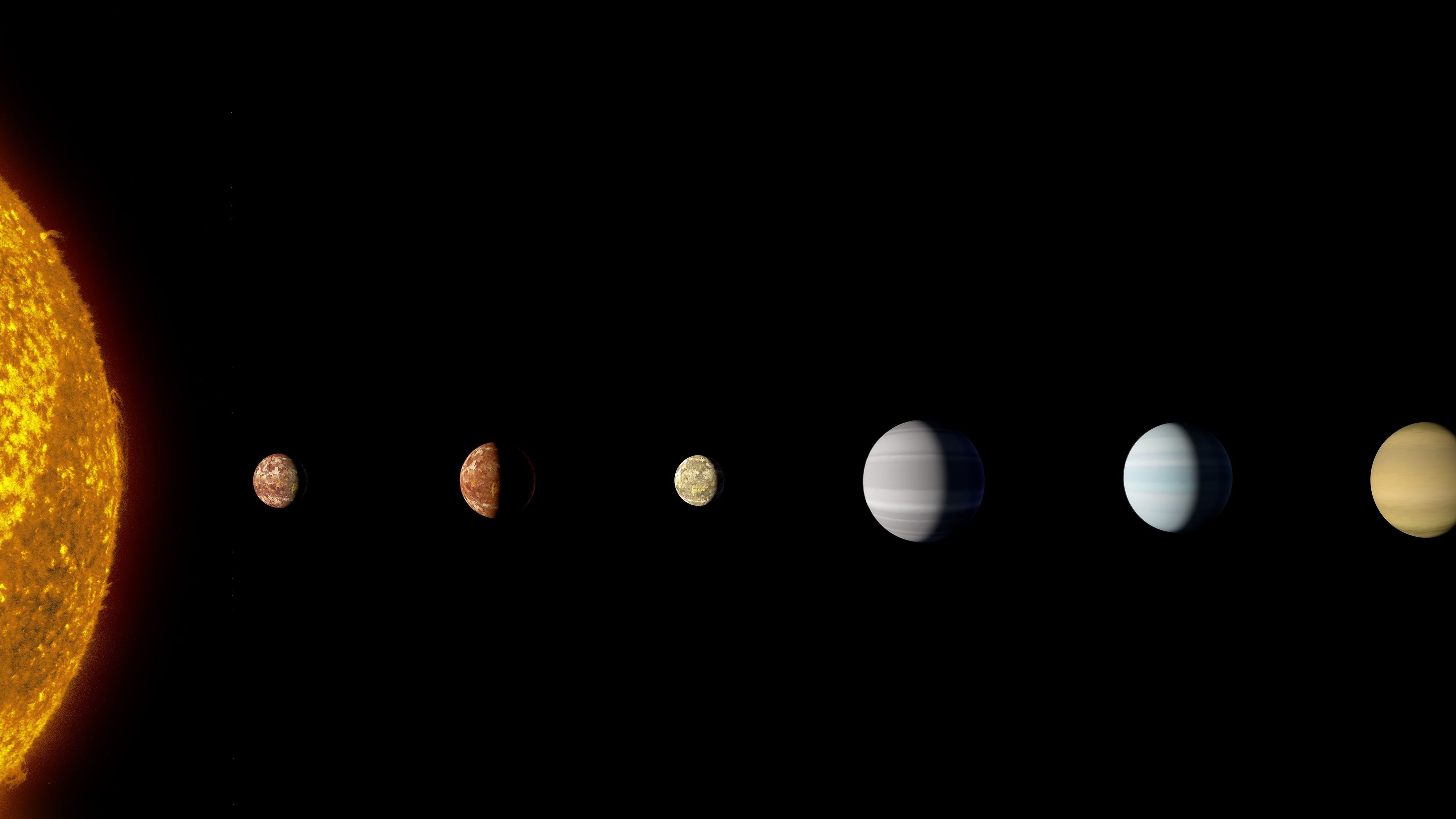

A solar system with as many planets as our own has been discovered, making us tied for the most planets revolving around a single star known so far.

Nasa made the discovery using data from its Kepler Space Telescope combined with machine learning from Google.

“Just as we expected, there are exciting discoveries lurking in our archived Kepler data, waiting for the right tool or technology to unearth them,” Nasa’s astrophysics director Paul Hertz said.

Kepler 90-i lives 2,545 light-years from Earth and, like the rest of the planets in its solar system, is closer to its sun than Earth is.

It means that life as we know it has no chance of existing, with the planet’s average surface temperature believed to exceed 800F (426C). Its outermost planet, Kepler-90h, orbits its planet at a similar distance to Earth.

It was discovered using machine learning technology from Google, which spots patterns in data sets, to sift through old Kepler data.

The Kepler telescope finds planets by observing the miniscule change in brightness that happens when a planet passes a star. Researchers Christopher Shallue and Andrew Vanderburg trained a computer to learn how to identify planets using that Kepler data.

“The Kepler-90 star system is like a mini version of our solar system. You have small planets inside and big planets outside, but everything is scrunched in much closer,” said Vanderburg.

Shallue, a senior researcher with Google AI, became excited about the prospects for machine learning in space exploration when he realised just how much data Kepler had gathered over the past four years.

“Machine learning really shines in situations where there is so much data that humans can’t search it for themselves,” he said.

Automated tests, and sometimes human eyes, have previously been used to look through the most promising planetary signals from Kepler’s dataset of 35,000 potential planets. Until now the weaker signals have traditionally been missed using that method.

But after training the neural network to identify transiting exoplanets from Kepler’s 15,000 strong pre-vetted exoplanet list, which it did correctly 96% of the time, the researchers set the network on to searching for weaker signals in star systems that already had multiple planets confirmed.

“We got lots of false positives of planets, but also potentially more real planets,” said Vanderburg.

“It’s like sifting through rocks to find jewels. If you have a finer sieve then you will catch more rocks but you might catch more jewels, as well.”

The strategy has already paid off, with a sixth, Earth-sized, planet being discovered in the Kepler-80 system.

Vanderburg said that despite the AI having “clear areas” where it struggles, they have ideas on how to improve it.

“We hope that eventually we’ll be able to use this to search the entire Kepler dataset,” he said.