The sun is losing mass and weakening its grip on the solar system, scientists have found, after analysing Mercury’s orbit.

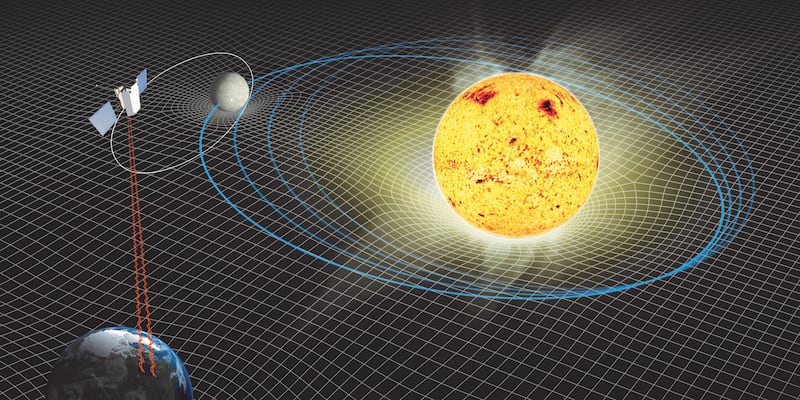

Researchers from Nasa and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) measured the rate at which the solar mass is being lost by studying changes in the orbit of Mercury, the planet closest to the sun.

They said the actual rate of solar mass loss, based on observations over seven years, was only slightly lower than what was predicted by previous models.

Scientists previously predicted that the sun would lose mass by one tenth of a percent over 10 billion years.

According to Nasa, the loss is “enough to reduce the star’s gravitational pull and allow the orbits of the planets to spread by about half an inch (1.5cm) per year per AU (an AU, or astronomical unit, is the distance between Earth and the sun: about 93 million miles)”.

The new value is slightly lower than earlier predictions but has less uncertainty, the US space agency added.

The calculations take into account Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity, which was theorised more than a century ago and proven in 2015.

Einstein said that massive objects, such as the sun, have the effect of distorting the space-time continuum around them, with Mercury showing this effect most clearly because it is closest to the star.

Study leader Antonio Genova, of MIT, said: “Mercury is the perfect test object for these experiments because it is so sensitive to the gravitational effect and activity of the sun.”

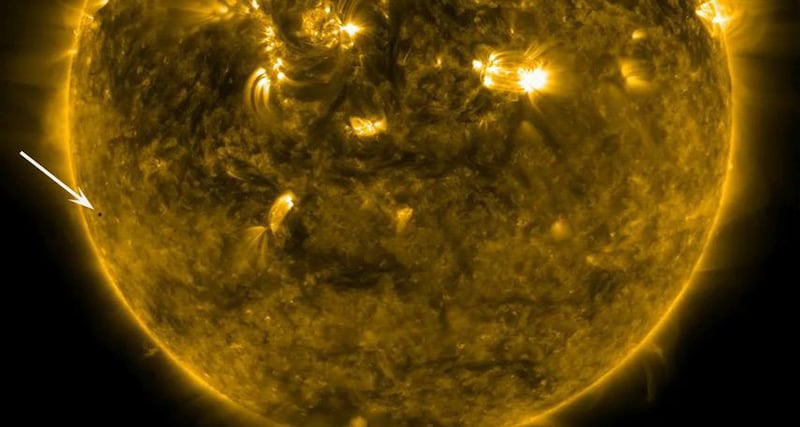

The researchers looked at data from Nasa’s MESSENGER spacecraft, which made three fly-bys in 2008 and 2009 and orbited the planet from March 2011 through April 2015 before crashing into it.

They analysed the subtle changes in Mercury’s motion from radio tracking data to learn about the sun and how its physical parameters influence the planet’s orbit.

They used the data to improve Mercury’s charted ephemeris – the road map of the planet’s position in the sky over time – and determine the changes in its perihelion, the closest point to the sun during its orbit.

The researchers also took into account how the sun’s interior structure – called oblateness (a measure of how much it bulges at the middle) – affects Mercury’s perihelion.

Study co-author Maria Zuber, vice president for research at MIT, said: “The study demonstrates how making measurements of planetary orbit changes throughout the solar system opens the possibility of future discoveries about the nature of the sun and planets, and indeed, about the basic workings of the universe.”

The study is published in Nature Communications.