People with limited mobility or paralysis could be able to use their hands again thanks to a robotic exoskeleton which can be controlled by brainwaves.

The lightweight and portable devices are being developed in the Geneva lab of Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne (EPFL) and can restore functional grasps for those with physical impairments.

It is hoped that refined versions of the kit will allow people to complete meaningful daily tasks.

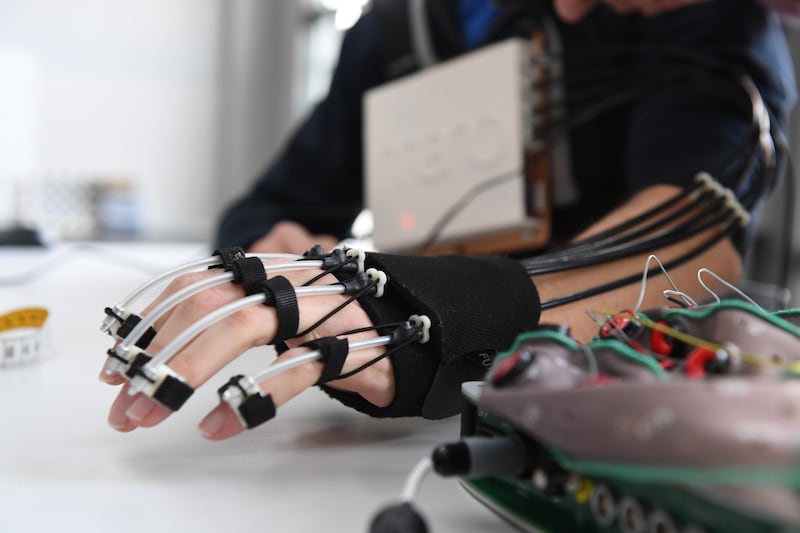

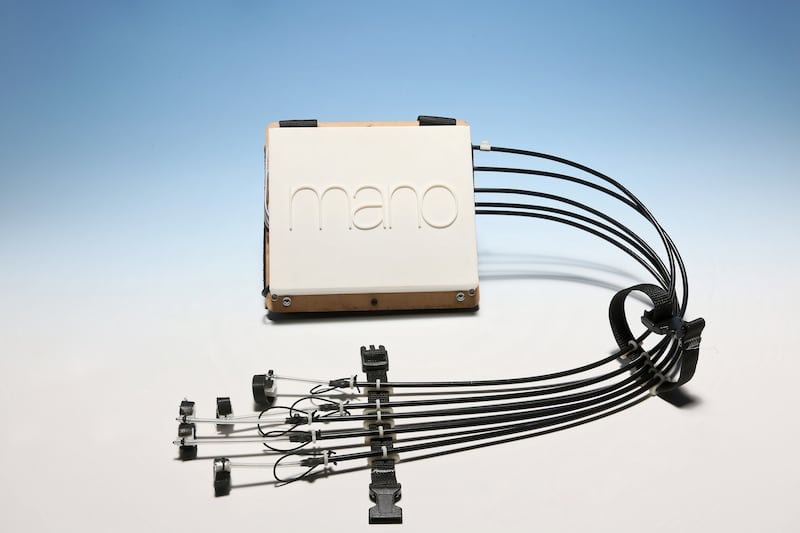

The device sits on the back of the hand with metal cables acting as tendons running down the fingers and thumb. They connect to a pack worn on the chest which contains the motors and power source.

It is attached to the hand via a Velcro cuff and Velcro loops on the fingers.

It is also linked to an EEG headset which measures users’ brainwaves but can also be operated via voice commands directed to a smartphone or eye-movement monitoring, depending on the wearer’s needs.

EPFL scientist Luca Randazzo is developing the exoskeleton with the Defitech chair in Brain-Machine Interface Jose del R Millan. Details have been published in the January edition of IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters.

The open design of the exoskeleton means the inside of the hand – the palm and fingertips – remains uncovered to allow a user to be able to grasp and work with objects and maximise sensations.

The chest-pack contains motors which can push and pull on the different cables, flexing the fingers when the cables are pushed and extending them when pulled.

“During testing, they found that the hand motions induced by the device elicit brain patterns typical of healthy hand motions,” said a spokesman for EPFL.

“But they also discovered that exoskeleton-induced hand motions combined with a user-driven brain machine interface lead to peculiar brain patterns that could actually facilitate control of the device.”

“This enhanced control of the hand-exoskeleton with brainwave activity is most likely due to higher engagement of subjects facilitated by rich sensory feedback provided by the nature of our exoskeleton,” explains Millan.

“Feedback is provided by the user’s perception of position and movement of the hand, and this proprioception is essential.”

The hand-exoskeleton has been tested with patients with disabilities due to strokes and spinal cord injuries. The next steps involve improving the system both for assistive purposes, for performing tasks at home, or even as a tool for rehabilitation.

“The hope is that by combining seamless human-machine interfaces and portable devices, these kinds of systems could enable and promote functional use in meaningful daily tasks,” added Randazzo.