Nasa’s Juno spacecraft has gathered data on Jupiter revealing details never seen before, including a range of powerful cyclones.

While extensive studies have been made regarding its surface, scientists knew very little about the inner structure of the largest planet in the solar system.

A team of international researchers analysed the Juno data and the results have been published in a four-article collection in the journal Nature.

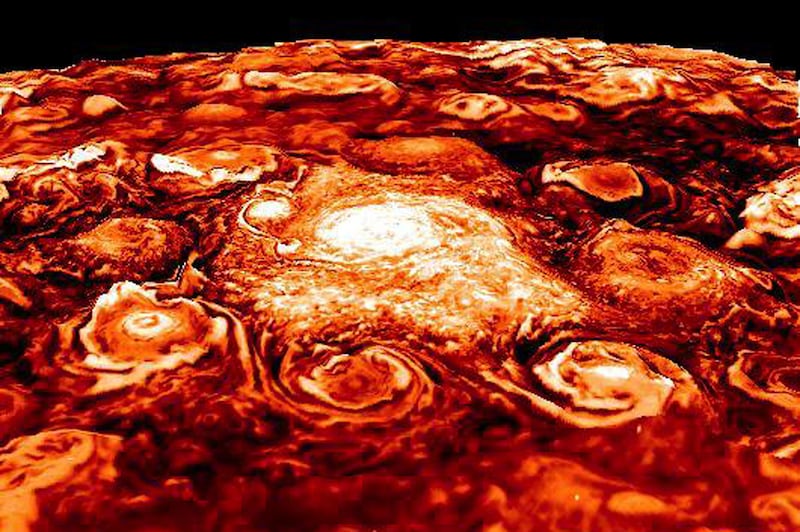

The new findings show that Jupiter’s famous striped bands extend to a depth of about 1,900 miles (3,000km) below the surface.

These bands are caused by powerful jet streams five times as strong as the most intense hurricanes on Earth, reaching 220mph (350kph).

The researchers uncovered a constellation of nine cyclones over Jupiter’s north pole and six over the south pole.

According to the scientists, these powerful air currents are capable of distorting the planet’s gravitational field, causing asymetries.

Luciano Iess, Juno co-investigator from Sapienza University of Rome and and lead author on a Nature paper on Jupiter’s gravity field, said: “Juno’s measurement of Jupiter’s gravity field indicates a north-south asymmetry, similar to the asymmetry observed in its zones and belts.”

According to Nasa, the more dense and powerful the jets, the greater impact they are likely to have on Jupiter’s field of gravity.

Yohai Kaspi, Juno co-investigator from the Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot in Israel, and lead author of a Nature paper on Jupiter’s deep weather layer, said: “Until now, we only had a superficial understanding of them [the striped bands of Jupiter] and have been able to relate these stripes to cloud features along Jupiter’s jets.

“Now, following the Juno gravity measurements, we know how deep the jets extend and what their structure is beneath the visible clouds.”

The findings also suggest that beneath these intense raging storms, the planet rotates as a solid body.

Tristan Guillot, a Juno co-investigator from the Universite Cote d’Azur in Nice, France and lead author of the paper on Jupiter’s deep interior, said: “This is really an amazing result, and future measurements by Juno will help us understand how the transition works between the weather layer and the rigid body below.”

Jonathan Fortney of the University of California, Santa Cruz, who was not involved in the research, called the findings “extremely robust” and told the Associated Press that they show “high-precision measurements of a planet’s gravitational field can be used to answer questions of deep planetary dynamics”.

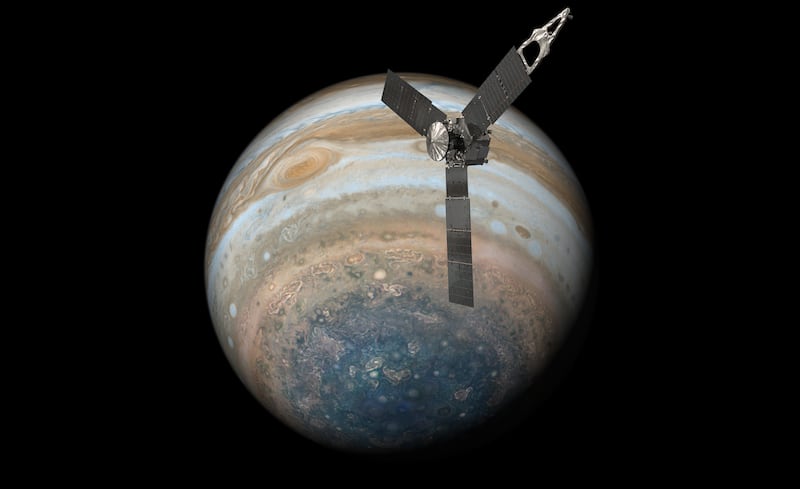

Launched in 2011, Juno has been orbiting Jupiter since 2016 and sending back high-resolution images of the planet.

It is the second spacecraft to circle the planet, following the footsteps of Galileo which monitored Jupiter from 1995 to 2003.