IT is just over three months since the first person in Northern Ireland - and on the island - tested positive for coronavirus.

A woman travelling from northern Italy with her child flew to Dublin airport and got on the Enterprise train to Belfast.

Information on the virus and where suspected cases were being tested was practically non-existent up until that point, with health service press offices citing "patient confidentiality".

In an age of social media, this lack of disclosure sent the rumour mill into overdrive as reports of 'deep cleans' in hospitals along with grainy pictures of staff in white hazmat suits introduced a fear factor.

Chief Medical Officer (CMO) Dr Michael McBride made the announcement about that first case in late February - but secrecy around the woman's precise travel details (much of which was on public transport) continued, sparking concerns a time when the death rate in the Chinese city of Wuhan, the epicentre of the global pandemic, was rocketing.

Public health experts north and south issued assurances that they had worked together to track down all those potentially at risk.

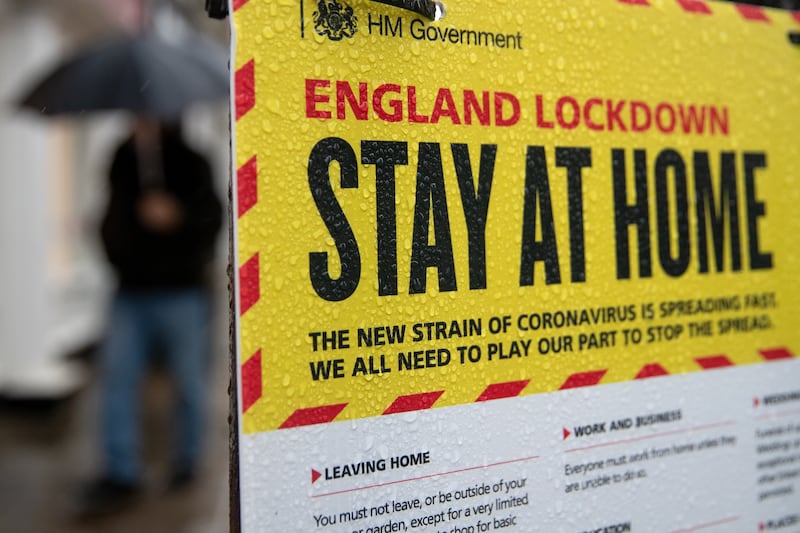

As the north begins to ease itself out of lockdown restrictions imposed 11 weeks ago, reflecting on those early stages and the point we're now at when more than 700 people have lost their lives raises many questions about the system's planning and communication strategies.

Saturation coverage has been given to concerns about testing, contact tracing, PPE shortages and protection of care homes.

There has also been repeated criticism around transparency, with the Department of Health called out by a UK government watchdog over appalling "gaps" in its published data - and a 'dashboard' on the outbreak only operating at full tilt in recent weeks.

Figures released last Friday by Nisra - which comes under the Department of Finance and collates Covid-19 fatalities differently - revealed that more than half of the north's deaths relate to vulnerable care home residents.

Health chiefs have been accused of putting hospital 'surge' planning ahead of care homes - a claim strenuously denied by health minister Robin Swann, who insists that work was constantly "going on behind the scenes" for months.

From the outset, the difficulties for top NHS officials making decisions about suppressing an invisible virus in a population that normally moves so freely - while trying not to create alarm - cannot be overstated.

"Don't panic" was the phrase frequently used by Mr McBride and other Public Health Agency (PHA) doctors in early media briefings alongside repeated messaging on hand-washing.

Prior to March 13, testing of people with symptoms in the community was taking place alongside extensive tracing of those who came into contact with positive cases.

Successful pilots such as a drive-through testing facility at Antrim Area Hospital were welcomed, while the importance of self-isolation for those who had travelled from "hotspot" countries was hammered home.

Some pupils returning from ski trips in Italy were among those quarantined, while a Mid Ulster league soccer match involving a player who tested positive saw efforts made by authorities to track down all those on and off the pitch he was in contact with.

Belfast was chosen as one of 12 regional testing facilities in the NHS with a laboratory based at the Royal Victoria Hospital site - but it was clear even at an early stage that capacity was severely limited, with only 40 tests per day carried out in early March.

Throughout this period, the public was told that decisions were being "guided by the science". However, a Downing Street briefing heard earlier this month that UK "capacity" and resources were an issue and led to what is now considered a catastrophic decision to abandon widespread testing and contact tracing in mid-March. A u-turn has since been performed.

In Northern Ireland a decision was taken in March to follow the lead of Prime Minister Boris Johnson's scientific advisers, at a time when World Health Organisation (WHO) experts stressed the way to beat coronavirus was to "test, test, test".

Tightened criteria meant that swabbing was limited to patients who were admitted to hospitals or had serious underlying medical conditions. Health workers were also eligible, but the first two groups had priority. Contact tracing was finished.

Meanwhile, the Republic followed a reverse strategy and dramatically increased its testing and tracking.

Frontline workers in the north expressed their alarm at the move, with a paramedic who tested positive revealing to The Irish News that he treated 50 patients in the two weeks before he was ill when he had no symptoms - yet no efforts were made to alert them or test even his paramedic colleagues "as per UK revised guidelines".

The case of former Cliftonville football coach Harry Fay, who begged to be tested in an A&E department and was only swabbed after he collapsed on a hospital floor - he was positive and gravely ill - also exposed major flaws in the system.

Meanwhile, severe shortages in appropriate PPE masks and kits for hospital and social care staff - a crisis mirrored across the world - led to one senior medic describing the "burning anxiety" for frontline NHS workers before the projected surge had even begun.

Such was the level of fear among some nurses about lack of protective clothing that they sought advice about making wills.

Unlike in England, a feared death toll of many thousands did not materialise and a specialist 'Nightingale' facility at Belfast City Hospital for coronavirus patients has now been stood down.

Testing has been significantly ramped up again - with more than 50,000 people in the north now swabbed and over 4,700 confirmed cases - while a new enhanced contract tracing programme began a fortnight ago, the first to do so in the UK.

Throughout the epidemic, public health experts have led calls for an all-island approach to tackling the crisis, saying it is the only way to come out of lockdown with the same level of testing north and south of the border, particularly at ports and airports.

With the focus now firmly on tackling the virus in care homes as universal testing is rolled out as well as deployment of NHS staff, attention has also turned to a feared second surge and how it will impact the most vulnerable.

In the absence of a vaccine, the extraordinarily steep learning curve of the past three months should help guide health chiefs in preparing for an autumn spike.

Hospital waiting lists, already the worst in Europe before the pandemic, must also be tackled while funding and support for GP and community services is crucial.

The signatories of a 'Memorandum of Understanding' on April 7 between the health departments north and south must also stick to their pledge of "strong co-operation" to stay out of lockdown, with their agreement acknowledging the "Covid-19 pandemic does not respect borders".

The task will not be an easy one.