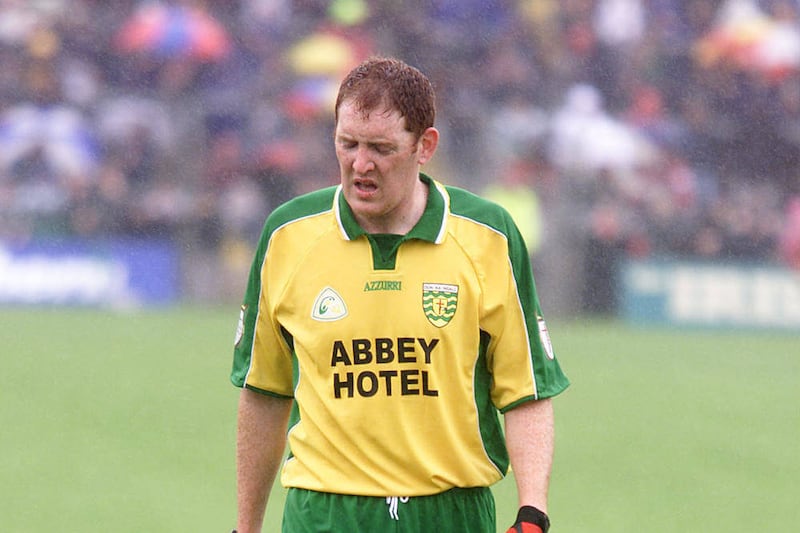

JOHN HARAN might have been born and raised in Donegal, but the former county midfielder received his football education in Galway.

A boarder at St Jarlath’s College, Tuam, Haran was on the 1994 Hogan Cup winning team. And that was no ordinary side. Haran holds the distinction of playing on a team which was essentially the `Galacticos’ of All-Ireland colleges football.

“In my first year team you had John Colcannon, Pádraic Joyce, John Divilly, Tomás Meehan, and Declan Meehan. Michael Donnellan was a year younger. Tommy Joyce was a year older. They were all on that Hogan team in ’94,” said Haran.

Interestingly, the first player listed by Haran was John ‘Scan’ Colcannon, an underage sensation who often eclipsed players who would later become household names. It’s scary to think what might have happened if Colcannon had made the leap to senior county level.

Recalling the exploits of his peers, Haran said: “I think Pádraic Joyce (GPA footballer of the Year in 2001), Michael Donnellan (Texaco Footballer of the Year in 1998) and Declan Meehan (GAA Footballer of the Year in 2001) all won the Player of the Year awards. For three players from a Hogan Cup team to win a Player of the Year award is phenomenal.”

But how did a boy from Letterkenny end up boarding in St Jarlath’s? The answer lies with Haran’s father, a native of Sligo, a Garda, and a football fanatic.

“My brother Eamon went down the year before me, then I went down in September ’89 as a first year boarder.

“The story my father gave was that if there was any football in these boys then they would get it out of them down in Jarlath’s. That was it.

“Lesley McGettigan would have gone down before us. He was a friend of the family. He won a Hogan Cup medal in ‘84.”

It was the scoring power of Pádraic Joyce and the mercurial brilliance of Michael Donnellan which underpinned Galway’s All-Ireland victories in 1998 and 2001. Joyce and Donnellan continued Galway’s tradition of producing fearsome forwards. After Galway’s victories over Armagh and Derry en route to Sunday’s qualifier clash against his native county, Haran believes Donegal need to be on their guard.

“When Galway have forwards they always seem to be a wee bit cocky. They always play with their heads up and their chests out. That is the nature of them. They don’t lack confidence. A Galway team with good forwards is always dangerous. Forwards win games so Galway are dangerous.”

Having fallen into an abyss, it seems new manager Kevin Walsh is guiding his county back to better times.

It could be argued that the Tribesmen have struggled to recover from the blow which was delivered when St Jarlath’s ceased to be a boarding school. With 12 Hogan titles, the Tuam institution is the most successful football school in the country. But for Galway, it was more than a school. St Jarlath’s served as an underage development academy.

“St Jarlath’s used to do all that work for Galway. It attracted good footballers. If you were a good footballer and you were from a club 25 miles away, your parents might have made the sacrifice for you to go their as a day boy or a boarder. Now Galway have to stand on their own two feet,” said Haran.

As a former boarder, Haran is well placed to comment on how the school rose to being the most decorated college in the Hogan Cup.

The American management consultant Peter Drucker coined that phrase that `culture eats strategy for breakfast’. Listening to Haran recount his days at St Jarlath’s, it’s difficult to disagree with Drucker’s theory.

With football training that consisted of playing matches, Haran maintained: “The whole thing was tradition.”

To illustrate his point, Haran pointed to the daily ritual of `going out on the stump’.

“School finished at four o’clock and you got a cup of tea after school. You then lined up and the priests would take your name and give out the footballs. There could be 30 footballs. You would just have lines of boys from leaving cert down to first year waiting to get a ball. You would have your crowd of mates and away you went. It was called `going out on the stump’. I don’t know what it meant. You just went out on the stump. You went out and kicked ball and had the craic. That went on day in and day out, kicking about and having the craic”.

What about the boys who didn’t like football? They also became subsumed in the school’s obsession with the game.

“There was a video club and a photography club for the boys who didn’t play football. These boys would go round making previews for the match. They’d interview players and teachers and first years and then it would be shown on the night before a Championship game. Everything was centred around the football.”

In an era when verbal provocation, play-acting and cynicism have become the norm, Haran said a very different philosophy prevailed at St Jarlath’s.

“They’d nearly take you off if you got a yellow card. It was frowned upon, especially by the priests and the principal, Father Maloney. They would have been disgusted with you. To be sent off, no-one ever got sent off. If you got sent off, you might as well pack your bags. There was no such thing as chatting back to the referee or making a bad foul. It was all sportsmanship and everything was done the right way.”

Given the culture which permeated St Jarlath’s, it’s little wonder Galway have struggled to adapt to the harsh realities of modern football. Blanket defences. Sledging. Diving. Cynical fouling.

It’s now how John Haran was schooled.