AGAINST a backdrop of technicolor graffiti that adorns the shutters in Garfield Street towards the bottom of Royal Avenue, Hugh gets to work.

“Can you look off up that direction please?”

“Just cross your arms this time and look at me”

“Stop closing your eyes”

It’s July 2016 and Wayne McCullough is back in Belfast for the first time in a while. It is a reuniting of old friends and, in between bursts of the camera, the ‘Pocket Rocket’ and pugilist turned photographer Hugh Russell share stories about Olympic days of yore.

The Rio Games are only a matter of weeks away; little did we know there would be no medals coming back from Brazil to add to the collection bolstered by Russell’s 1980 bronze and McCullough’s Barcelona silver 12 years later.

As the final pictures are set up and shot, a couple of likely lads stagger into view from nearby North Street.

“Possssssser,” comes a half-hearted shout in the direction of the former world champion, whose back is to the shutters,

McCullough’s eyes narrow, just for a second. And then.

“…houl on, is that yer man?”

The pair briefly look at each other then back towards the shutters.

“It f**kin’ is too…”

“Wayne McCullough!”

“Alright mate? Whataboutyeeee?”

Within seconds, arms are around shoulders, warm handshakes are being exchanged and selfies taken. A fleeting moment of tension replaced by recognition for one of the city’s most famous fighting sons.

They looked just about old enough to remember McCullough in his mid-90s pomp, if perhaps a few years too young to have seen the fella carrying the camera in action on the other side of the lens.

His time would come though.

Walking back towards the office, we stand at the junction where Donegall Street and Royal Avenue meet. Traffic has stopped to the left but is still coming straight ahead.

Parked in front of the red light, bound for York Street, the engine of a Translink bus rumbles impatiently as the driver window begins to roll down.

“I remember going to see you in the Ulster Hall. I was at all your fights.”

Russell nods back, an embarrassed smile creeping across his reddening face. All of a sudden the camera bag on his back looks bigger than him.

But the man at the wheel isn’t done yet.

“I was at the King’s Hall for the second Larmour fight as well,” he hollers, raising his voice another octave to make himself heard above the midday din.

Red turns to amber as the window winds up, until Russell can hold his tongue no longer.

“Did you say the second Larmour fight?” he shouts back across the lanes, half-giggling as the bus brakes hiss before take-off, “the first one was better.”

***********************************

MARCH 1, 2018. Tomorrow marks 35 years to the day since the second of those two almighty wars that reignited boxing in Belfast during the fallow period before Barry McGuigan’s ascent to super-stardom.

Inside the Irish News offices Larmour-Russell III is about to take place, only this time the gloves are off. And instead of hordes of fans lustily roaring them on, there’s only me, Paddy Maguire - Larmour’s old trainer - and a dictaphone for company.

It is a privileged audience.

Russell is still involved with the sport through his day job and work with the British Boxing Board of Control while Larmour helps out clubs across the city.

Both men are grandparents now. Larmour, at 68, is retired and, along with Maguire, regularly travels the length and breadth of Ireland to meet old friends and former foes.

It seems like a lifetime since they were being posed for photographs with forebears Freddie Gilroy and John Caldwell outside the King’s Hall, standing on the shoulders of giants before the long-awaited return to the home of big-time boxing.

Twenty years earlier, that spiteful rivalry captured the imagination of local fight fans like no other, and now the baton was being passed. The new kids on the block didn’t disappoint.

Russell and Larmour have met at various functions through the years, chatting and exchanging pleasantries at welcome home celebrations for men like McCullough and Carl Frampton, the latest carriers of the flame.

But they have never sat down together to relive the two fights that would come to define them. Blood-soaked brawls that are talked about to this day; battles that still prompt bus drivers to roll down windows and bellow across traffic.

Thirty five years on, what better time than now?

“I don’t think you’d have got Gilroy and Caldwell together in a room like this,” chuckles Larmour.

And he’s right. Only two years separated Gilroy and Caldwell so, right the way through from amateur to pro, they grew up in each other’s pockets. One could not escape the spectre of the other – it was only natural that acrimony developed.

There is 10 years between Russell and Larmour. So when Russell was just a small, skinny kid learning his trade, Larmour was sweeping up Ulster senior titles and mining Commonwealth medals in far off shores.

“I grew up all my days watching Davy Larmour fighting Neil McLaughlin. You’d have been going to the fights and watching these guys,” says Russell.

And, long before being thrust into the lion’s den, the pair shared the ring for the first time in the humble surroundings of the Holy Family gym.

“I was sparring Jimmy Carson’s father and you came in to warm me up before it. I reckon you were only nine or 10 years old... you were only up to there,” recalls Larmour, holding his hand up around his midriff, “chasing me around”.

“Hitting you on the belly,” smiles Russell.

The young man would soon start to make waves of his own though, winning a first Ulster senior title in 1978 before returning home with a flyweight bronze from that summer’s Commonwealth Games in Edmonton.

McGuigan, who topped the podium in Canada, had long been seen as a pro star in the making but it was Russell who returned from the 1980 Olympics with Ireland’s sole boxing medal.

The man who would go on to be dubbed ‘the Clones Cyclone’ turned over not long after falling short in Moscow, and Russell wasn’t far behind, following McGuigan to Barney Eastwood’s growing gym and making his debut in late 1981 – a week before his 22nd birthday.

Larmour managed himself but would have trained regularly at Eastwood’s. Yet even when Russell’s familiar face became a permanent fixture, the prospect of the pair meeting down the line still failed to register.

“I never envisaged fighting Hugh,” admits Larmour.

“He had just turned pro and my focus was on the British title... Hugh was only new to it, he wasn’t in the picture at that time.”

“It never really crossed my mind either because I turned pro as a flyweight,” adds Russell. “I was competing at flyweight at the Olympics and the Commonwealths... I saw myself as a flyweight.

“But to get fights in the pro game I had to move up to bantamweight, and I was lucky enough to put together a clatter of wins that got me rated.”

Within 10 months they were on a collision course and, while Larmour and Russell may not have seen it coming, one man most certainly did.

***********************************

EVEN taking Russell’s rich amateur pedigree into consideration, pitching an eight-fight pro into a 12-round bout for an Irish title, and a British title eliminator, against a grizzled veteran was a dangerous move.

But it was a calculated risk Barney Eastwood felt he had to take at a time when professional boxing in Belfast had yet to waken from its post Gilroy-Caldwell slumber.

And besides, he was confident that, despite Russell’s relative inexperience without a vest (the furthest he had been was eight rounds, and that distance was completed only once), his man had the tools to take care of Larmour and earn a crack at John Feeney’s Lonsdale belt.

“Something was needed to lift the boxing at that time,” says Eastwood. “I suppose it was a risk, but I always fancied that Russell would outbox him.”

The date was set for October 5, 1982 - a Tuesday night at the Ulster Hall.

Two Belfast boys, two decorated amateurs. The young pretender versus the old dog seeking one last shot at the big time. The narrative had already written itself – it was the easiest sell of Eastwood’s career.

That Russell was from the nationalist New Lodge while Larmour was a son of the Shankill didn’t even come into it, despite the backdrop of the Troubles raging on the streets.

This was the fight the boxing public had been crying out for and the hype machine, unsurprisingly, swept into overdrive.

“I just remember my father saying ‘you’ve got to go to this fight’, and he got us two tickets,” recalls Eamon Loughran, the former welterweight world champion who travelled from Ballymena to Belfast for the big night.

“The buzz was about straight away, and the feeling was that if you could get tickets, or if you could get in at all, you were lucky.”

“In my view, that was my first real pro fight,” says Russell.

“That was a big step up. I was very young into the game, less than a year, and you’re fighting somebody you had watched train and looked up to all your life as ‘the man’.”

Punters turned up early to get their spot. The Ulster Hall’s capacity for a boxing match was 700 but, by the time the main event was about to begin, numbers had swelled far beyond the official limit.

“There were 1,250 paying customers in the hall – we broke all rules and regulations,” laughs Eastwood.

“They were packed in up on the balconies at the windows, but even the aisles between the seats were completely filled with people sitting on their hunkers. The fighters could hardly get into the ring or out of the ring.

“You couldn’t move.”

By the time English referee Mike Jacobs waved them together, electricity filled the smoke-thick air.

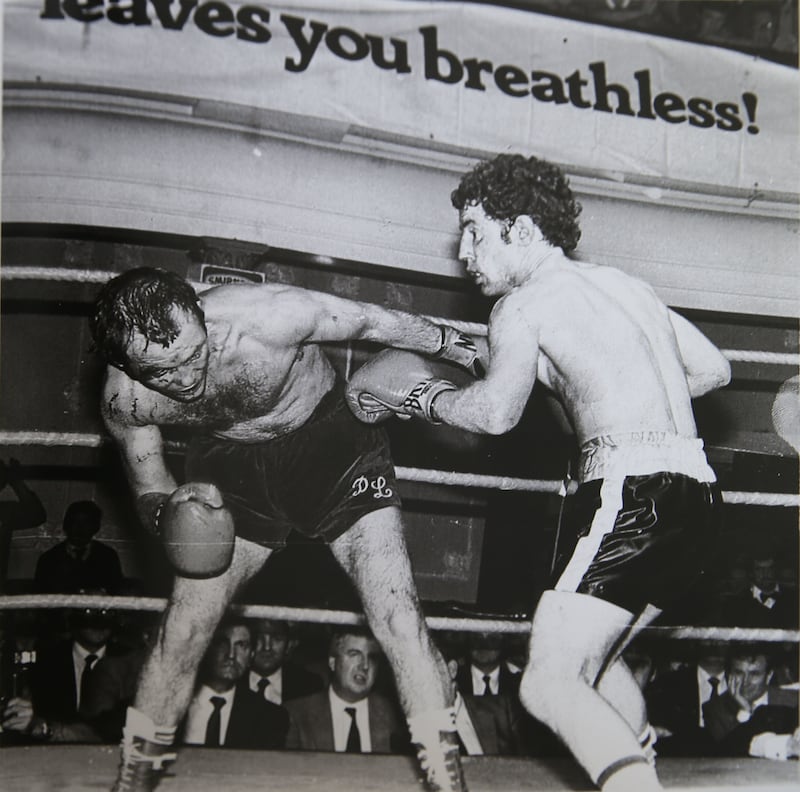

An intriguing battle unfolded as the bigger Larmour set about walking down his flame-haired opponent, who was using his slick southpaw skills and clever footwork to steer clear of danger.

Larmour’s right hand was still finding a home, however, and as the fight headed into the ‘championship rounds’ - 10, 11, 12 - the outcome hung in the balance.

The canvas more closely resembled a butcher’s apron by now, the faces of both men a mask of blood – something which, 35 years on, took Larmour by surprise as they swapped stories about their respective war wounds.

“Naw... I don’t think you were cut?” he said before a few seconds of stunned silence.

“Oh I was badly cut,” barked Russell.

“In the first fight?”

"Oh aye, I was badly cut... I’m glad you couldn’t see because somebody was hitting me!”

“The two of you were cut,” confirms Maguire, acting as referee before Russell comes back swinging again.

“Don’t I know it,” he says, eyes widening: "I didn’t think I’d hit you as hard as that...”

Inside the ring, each blow that landed was met with raucous approval, especially as the final bell neared. And, despite his relative inexperience, it was Russell who dug deep and found something extra when it mattered to take a narrow 117.5 to 116.5 decision.

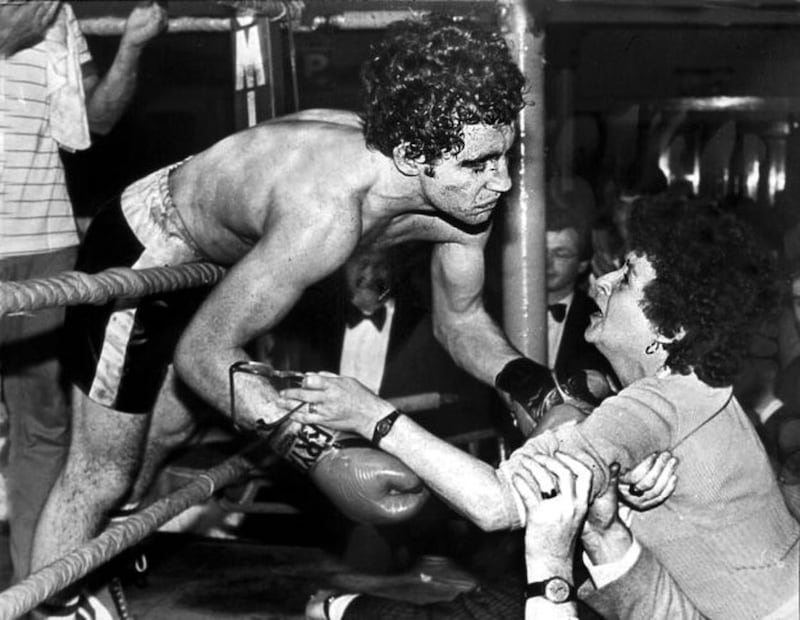

Brendan Murphy’s front page photograph of a battered and bloodied Russell leaning out through the ropes to kiss mother Eileen - horror and relief etched across her face - perfectly encapsulated the gory drama.

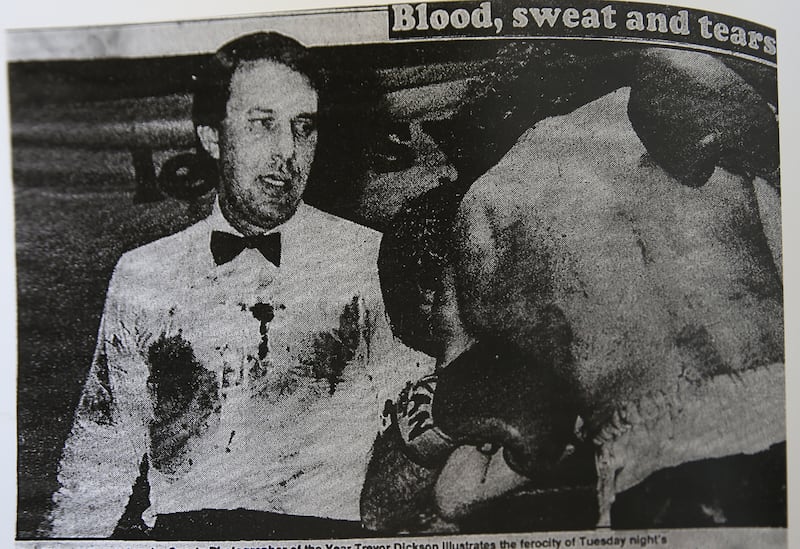

Indeed, when referee Jacobs went to pick up his shirt from a London dry-cleaners in the days after he was handed a letter asking that he report to the local police station, where he was subsequently grilled by CID.

A telephone call to the head of the British Boxing Board of Control was required to convince officers that the crimson-stained garment hadn't been left in such a state as a result of shadier endeavours during his time across the Irish Sea.

***********************************

THE thousand-plus punters filed slowly out into the night air, still bobbing and weaving, throwing uppercuts, squeezing the last drop out of the previous hour’s adrenaline surge. Behind the scenes though, it was a different story.

In the dressing rooms, cuts were still being tended, eyes examined, blood stemmed. Pain was starting to settle in and make itself known. Yet, unexpectedly for the two gladiators, they had not seen the last of each other.

Larmour takes up the tale.

“We were in the dressing room, and I was saying about needing to go up to the Mater to get stitched up.

“Somebody came in, I don’t know who it was, and said ‘Davy, how are you getting up to the hospital?’ ‘I’m driving up’, I says...”

Then the voice came again.

“You wouldn’t take Hugh up? He has no way of getting to the hospital.”

“Aye, tell him to come ahead,” was Larmour’s instant response, paving the way for what must surely have been the most awkward of journeys.

“So Hugh got in the back of the car,” continues Larmour before turning to his former foe, “I’ve always wondered how you felt getting in?”

“Sore,” replies Russell with a smile, “but not as sore as you.”

Was there much said?

“No, I don’t think so,” says Russell casting his mind back, “but it would have been a happier back seat than the front seat.”

“The funny thing about it was,” recalls Larmour, “I’m lying on a little bed [in the hospital] and there’s screens around me. The doctor comes in and he’s looking at me, sayin' ‘you’ve a couple of good cuts there, who did that on you?’

“I pulled the curtain back and said ‘he did!’”

They laughed at the time, and they laugh about it now.

However, it wouldn’t be long before they were pitched back into the trenches once more.

Barney Eastwood had made a promise that, should his man beat Feeney and land the British title, the first defence would be a return against Larmour.

He proved to be good to his word.

IN TOMORROW’S IRISH NEWS

“What I was getting now was a bonus. I was at my peak in the ‘70s, my sell-by date was passed and there was nobody more aware of that than me”

Davy Larmour sensed the end was near but couldn’t resist one last crack at securing the Lonsdale belt, on a night when he evened up the score