I GOT a new phone a few weeks back and, in the process of changing over, decided it was time for a bit of a declutter.

Apps that hadn’t been opened in a decade were removed once and for all. Old voice memos - usually barely audible interviews conducted on the side of a windswept pitch, or a few grunts from a frustrated manager in the tunnel after - take up more space than you’d think.

Then came the photos. Christ, the photos.

It was an arduous process, but one which also uncovered a rare gem lost in the mists of time.

Let me take you back to June 7, 2014. The first round of Chris Eubank jr’s 16th fight has just ended and, as he takes a seat on the stool, a familiar figure steps nonchalantly through the ropes.

Wearing a black waistcoat over a sleeveless white shirt, black slacks and a pair of black Chelsea boots whose shine – like his bald pate – have picked up the lights overhead, there is no mistaking Christopher Livingstone Eubank.

While veteran corner man Ronnie Davies busily mops junior’s brow, Eubank sr takes two deliberate paces backwards before stopping, leaning back a fraction and fixing his son with an almost contemptuous glare. This moment lasts for 25 excruciating seconds.

With round two about to get under way, he slips quietly to the side and out of the ring. No words spoken, no instructions given. It is one of the most brilliantly bizarre moments, embellished by Eubank sr’s response when later asked what it was all about.

“Ah,” he said, eyes widening as a smirk hung upon his lips, “there can be no talking while the exam is in progress.”

That image, no matter when or where it crops up, always raises a smile. And while thousands were deleted, including a right few of the kids, family gatherings etc, that one easily made the cut.

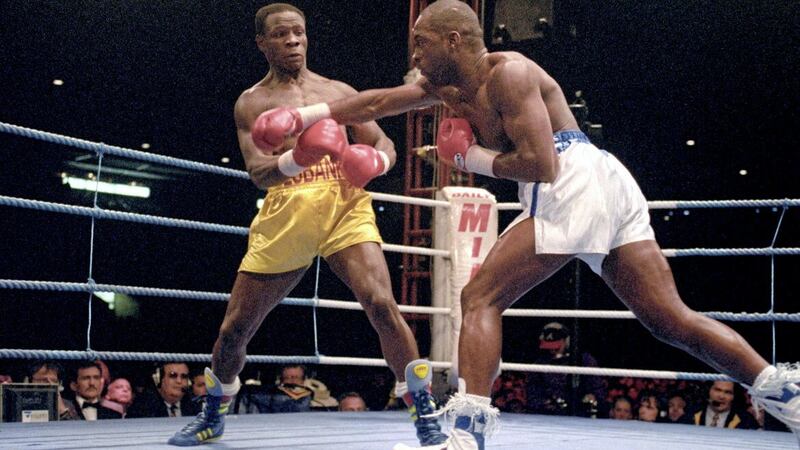

Chris Eubank has always commanded attention. For many who watched his star soar in the 1990s, when Eubank was a staple of terrestrial television’s Saturday night offering, his eccentricity was a turn off.

There was the posturing and preening, the haughty manner, the monocle, the riding crop or the cane, depending on the mood that took him on a given day.

Yet, regardless of what side of the fence you stood, Eubank was box office. And, unlike so many modern day fighters, there was substance to the swagger.

“The old man could fight,” was the matter-of-fact appraisal of Ronnie Davies, Eubank’s long-time trainer, when we spoke a few years ago.

“He came up hard. You couldn’t hurt him… he would walk through anything. He was one hard bastard.”

The showman was the perfect foil to the fighter, but for all the appearances on Gogglebox and Blankety Blank – as well as the playing up to his carefully-crafted image - Eubank has never been anybody’s fool.

After a summer spent trying to pin him down back in 2018, the search finally ended when we spoke about his two fights against Belfast man Ray Close. John Wischusen, Barry Hearn’s right hand man during that era and a close confidante of Eubank’s, did all the leg work.

“Monday, call him at 1pm,” came an instruction that was warily received after weeks of false starts. When he answered, the first question posed elicited a six second silence that felt like six years. This was going to be hard work.

And yet what unfolded over the course of an hour-long call was an insight into the curiosities of a unique character. The plummy accent that accompanied his soft voice and famous lisp was derived from the Seventies TV drama Upstairs, Downstairs, while its lavish costumes influenced his flamboyant style.

The slow, provocative walk to the ring, those long looks to the camera, nostrils flared, the pause on the ring apron, the dramatic hopping of the ropes - Eubank the showman came straight from a movie set.

“The Three Musketeers,” he said, “in this particular one Michael York played D’Artagnan. If you think of that character, if you think of Charles Bronson’s character in the movie Once upon a time in the West.

“These movies depicted an individual going into hostile environments so let me tell you, going to Belfast, it was beautiful. The Irish love a character, and who doesn’t adore defiance?

“So even if I hadn’t won a round on punches, I’d win it on foot movement and posturing, showing defiance to the crowd. I’d be a showman. If I didn’t win physically, by theatrics I would win.”

Around that time, Eubank was being linked with a potential trilogy match against Nigel Benn. Although it had been years since both men retired, the market for such carnival freak-show attractions was in its infancy. There was money to be made if they wanted it.

Benn was mad keen, Eubank less so. Listening to him explain why was a window into what lies behind that confident façade.

“Boxing is a way of life; you can’t do it part-time.

“After fights I’d be back in the gym on the Monday. I didn’t club. I was ashamed to go into night-clubs, to wine bars, because I thought people would think ‘oh this guy’s a fake because real fighters don’t come into these places’.

“And you know, now looking back, nobody thinks like that. No-one. It’s a normal thing but it was so prevalent in my mind and this is the reason why - it may sound funny, it may sound nonsensical. But the reason I was back in the gym on the Monday is because I knew I wasn’t that good.

“That’s the reason I kept on winning… because I knew I wasn’t that good.”

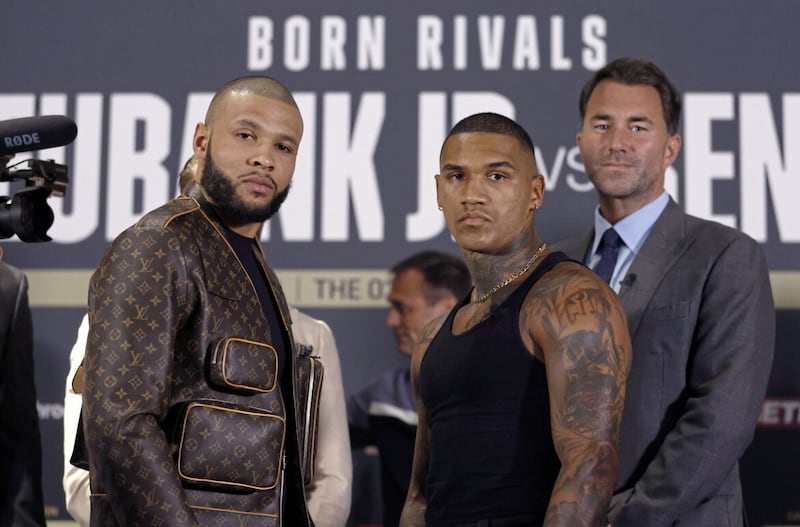

In eight days’ time, Eubank and Benn will clash once more – this time it is their offspring rekindling the rivalry.

Since the match was made, a brilliant clip of their fathers alongside Nick Owen on ITV Midweek Sport Special has resurfaced. Although placed beside each other, Eubank keeps his back to a smarting Benn throughout. As he speaks, Benn constantly interjects.

Eubank keeps going, until there is one interruption too many.

“You’ve had your time,” he snaps “let’s have some parliamentary procedure, alright?”

Benn’s eye-roll summed up his animosity towards his adversary. Thirty years on, Conor Benn brings all the lip-curling angst and attitude of the old man, that chip on the shoulder passed straight down the line.

Eubank jr has been around much longer and, despite never quite becoming a genuine world class contender, that toughness wasn’t licked from the stones. Occasionally he will indulge in a bit of braggadocio too, or let a solemn look linger into the camera, but it all feels a bit forced and fake. That’s not his fault.

After all, while the son may bear his name, there could only ever be one Chris Eubank.