Ohhhhhhh say can you see

By the dawn's early light

What so prouuuuuudly we hailed

At the twilight's last gleaming…

JUNE 1, 1991. Thirteen years earlier Brian Quinn had been lining out for O’Donovan Rossa’s senior hurlers. His late father Seamus ‘Nipper’ Quinn was involved in Antrim’s famous run to the 1943 All-Ireland final, and a fair chunk of his childhood was spent with hurl in hand.

June 1, 1991. Twelve years earlier Brian Quinn was part of the Larne side that lost out to Cliftonville for an Irish Cup final spot.

A few months later he was packing his bags for Merseyside, turning his back on teacher training college following an offer from Everton that he simply couldn’t refuse.

June 1, 1991. Ten years earlier - on the move again. Everton was great but he didn’t get a look in. One day the phone rings. It’s Brian Halliday, his old mentor at Larne, with a proposition that would turn his world upside down.

“How do you fancy coming out to Los Angeles and playing here?”

Only 21, his career was just opening out. Plenty before had gone back to the drawing board and come again. There was no shortage of English clubs interested in securing his services.

Glentoran boss Ronnie McFall wanted to take him back to Belfast. That would have been the easy option.

But he trusted Halliday implicitly.

“Where do I sign?”

June 1, 1991 – Foxboro Stadium, Boston.

Brian Quinn stands, arm across his chest, hand on heart, looking up at the stars and stripes. Yards away the familiar green, white and gold of the Irish tricolour catches the gentle evening breeze as over 51,000 people rise for the anthems.

Mick McCarthy stands at the head of a line of men in green shirts. Pat Bonner, Ray Houghton, Paul McGrath – Paul McGrath – Tony Cascarino. Legends all for their exploits beneath Italian skies just a summer ago.

On the other side, wearing the red, white and blue of the United States for the first time, stands 31-year-old Brian Quinn - the boy raised in Ballymurphy, the boy who still spoke with a broad Belfast accent.

The boy who left the city just as the Troubles strengthened its grip on the streets he called home.

IIIIIIIIIIIOOOOOIIIIIIIIIII

NEWSPAPERS lie scattered on the table in the front room of his mother-in-law’s house in Finaghy. Brian Quinn looks fresh after a morning in town, showing off his California tan in a pair of shorts that are at odds with the mizzly weather outside.

Now 58, he remains whippet thin, thanks largely to his role as San Diego soccer club’s director of coaching which sees him out on the field all day every day, directing operations.

Indeed, the night before we meet he organised a session for a group of kids at Aquinas Grammar School and the youngsters, while not exactly sure who had just been putting them through their paces, clearly sensed something different about their coach.

“Is he famous?” one asked our photographer.

“Does he play for Man United?” wondered another.

“Is he a millionaire?” queried a third.

“Sadly not,” says Quinn, laughing at the suggestion.

He and wife Sharon try to get home once a year to catch up with friends and family.

But there is one event coinciding with their return this time around that has taken Quinn right back to his earliest days.

“All the stuff I’m reading since I’ve been back about the Ballymurphy massacre,” he says, lifting that day’s copy of The Irish News which sheds new light on the awful events of August 1971, “that really comes back to me clearly because I do remember what I was doing that day…”

What were you doing that day?

“Throwing stones!” he says with a wry smile.

“I was at the Henry Taggart [the British Army base]. It’s probably the only day I remember where I didn’t get home that night.

“It was fun and games – you know, you’re 10-11 years old. You’re throwing stones, that was the thing to do and then I remember shots rang out and everyone just ran.

“This lady ended up putting six or eight people in her back room and all of us stayed there. The shooting went on through the night and she walked me home – the Henry Taggart was on the Springfield Road, I lived at the top of the Whiterock.

“When I went home, I remember my mother had a mattress across the front window, just in case. The youngest in our house were twins and she put them in the bath that night to sleep.

“It’s really vivid when you read back now…”

The escalation of the Troubles couldn’t have come at a worse time for the Quinn household, which was still coming to terms with the loss of husband and father Seamus the year before at just 46.

“I was almost 10 and, looking back now, it was more tragic than I really understood at the time because I was one of 10. I’m in the middle. My two older brothers were gone, my father had sent them to be Christian Brothers in Dublin, so after dad died my eldest brother came home straight away to go to work.

“My mum was a widow who didn’t work with twins who were three. I don’t know how she survived but, likely everyone else in those days, you get through.”

But neither his father’s passing nor the Troubles had anything to do with Quinn’s desire to seek pastures new.

He played Gaelic football and hurling for Rossa right the way up through the age grades, but only started taking soccer seriously in his early teens.

By 15 Quinn had already been over to Middlesbrough for a trial. The professionalism, the intensity and the competitiveness was a shock to the system. In his mind, that was that.

With plans to attend teacher training college and plenty to satisfy his sporting needs, Quinn was happy enough with his lot. But after starring for Larne in the Irish League, it wasn’t long before cross-water interest resurfaced.

He impressed at a pre-season tournament in Le Havre, performing so well against an Everton side including the likes of Kevin Radcliffe and Steve McMahon that the Toffees asked him over for a trial.

Within weeks he had signed a two-year contract but, given the competition to get into Gordon Lee’s starting 11, Quinn never got a start and wasn’t going to be re-signed.

At the end of the 1980/81 season, therefore, some tough decisions had to be made.

Coming home was under serious consideration.

“I loved Everton, loved Liverpool – I’d have stayed there forever if I had’ve been a little bit better.

“I was thinking about coming back but then I spoke to Mike Lyons, who was the captain of Everton at the time, and he said ‘don’t go back to Belfast son’.

“He told me I had a future.”

Brian Quinn had a future alright. He just had no idea it was over 5,000 miles away.

IIIIIIIIIIIOOOOOIIIIIIIIIII

“I didn’t even have a passport, that was my first thought, but Brian painted this picture where I didn’t question his motives”

BRIAN Halliday had always kept an ear to the ground. He was Brian Quinn’s number one fan and, having settled on America’s west coast himself, convinced his protégé – along with Sharon and baby daughter Nicola – to swap Liverpool for Los Angeles, Everton for the Aztecs.

“When I got off the plane it was maybe 90 degrees, heat I’d never felt before, but they liked me. There was a Brazilian coach, Claudio Coutinho, and the way I played was a good adjunct to what he had players-wise.

“He had Brazilians, a couple of Argentineans, a guy from Yugoslavia, American players, one or two Mexicans, good players. I fitted in because I was a busy midfield player who was going to get the ball and give it to somebody else.”

There might not have been the huge crowds and bear-pit atmospheres of the grounds back in England, but Quinn never looked back. He was enjoying the football and by the end of his first season in LA had shared a pitch with childhood hero George Best.

On the football front at least, life was good.

However, Sharon had found it harder to settle and when the Aztecs folded just a year after their arrival, the Quinns jumped at the chance of a move to Montreal, with Brian again rubbing shoulders with some greats of the game.

“We played against the Cosmos four times and ended up beating them in New York 4-2 in a play-off and I scored two. They had some amazing players, the likes of [Giorgio] Chinaglia, Franz Beckenbauer, [Johan] Neeskens, and these two smashing Paraguayans called Julio Cesar Romero and Roberto Cabanas.”

But when the North American Soccer League (NASL) was wrapped up at the end of the 1984 season, Quinn was once more left to consider his options.

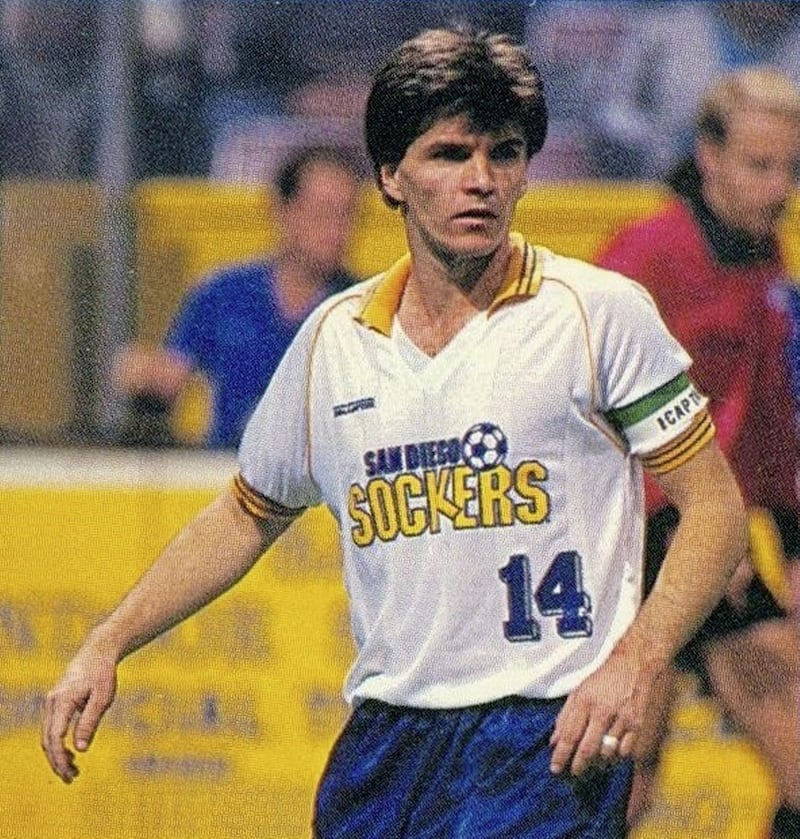

Still only 24, he was sounded out by English clubs but the pull just wasn’t there. And when the Major Indoor Soccer League was recruiting for the 1984-85 season, the San Diego Sockers came calling.

“All the guys who had played in the NASL either left and went home or stayed and played indoor. It became the top level of football in America, and I was in a really good team [the Sockers were the most successful franchise].”

Having only ever played 11 v 11, however, the indoor league was a whole new world.

“Basically it was like a hockey rink and you had a goalkeeper and five outfield players. It was way different from what we were used to but it was a good level, lots of one v ones, good technical players.

“It was like five-a-side on steroids.”

In 1979 Quinn had played a B international for Northern Ireland against New Zealand at The Oval. Twelve years on, and having only played indoor for the guts of the past seven years, any rekindling of international ambitions couldn’t have been further from the radar.

Even when he was granted US citizenship in April 1991, the priority had been his family, not football.

“It was a personal decision made for two main reasons. I wanted to stay in America, number one, and secondly one of my children was born in Belfast, the other in Montreal, our three other children were born in America, so we wanted to make sure that if anything ever happened, the kids had American citizenship.

“I hadn’t any thoughts about playing for the US. None whatsoever.”

But when the United States soccer federation recruited well-travelled coach Bora Milutinovic in the wake of a disappointing 1990 World Cup, suddenly everything changed.

“Bora was this kind of soccer pioneer - he was Serbian but he played in France, Mexico, travelled all around and was a fantastic coach. He was full of life, a big personality, and his mantra was ‘bring me everybody’.

“His assistant was a Polish guy called John Kowalski who had been around American soccer for 15-20 years, and I guess my name came up…”

IIIIIIIIIIIOOOOOIIIIIIIIIII

BRIAN Quinn reckons it was maybe five or 10 minutes into the first of 48 international appearances in the stars and stripes. Eager to impress after only a week’s training with his new team-mates, he was covering every blade of grass at Foxboro, giving orders and encouragement in equal measure.

Then Andy Townsend, trotting up the field a few yards ahead, turned around and fixed his eyes on Quinn.

“Oiiii,” he smiled in that familiar Cockney brogue, “you’re not American.”

The irony was not lost on the Belfast man.

“Yeah?” said Quinn, walking towards the Norwich City midfielder, “well you’re not Irish!”

The pair shared a laugh and went on about their business, the spoils eventually shared in a 1-1 draw, Eric Wynalda equalising Tony Cascarino’s opener.

That was the first of three times Quinn would play against Jack Charlton’s side, and he was captain when the US travelled to Lansdowne Road for a 1992 friendly.

The fact mum Kathleen, who had also attended the Northern Ireland B international in 1979, travelled from Belfast to Dublin to cheer on her boy made it all the more special.

“When you look back, it was fantastic.

“A lot of the other guys were maybe starting or in the early stages of their careers and I was coming towards the end, so I had a deep appreciation of the position I was in.

“I got to play Ireland three times, I played against Brazil in Brazil the night Roberto Carlos made his debut. There were so many great experiences.”

But Quinn wasn’t just tagging along for the ride.

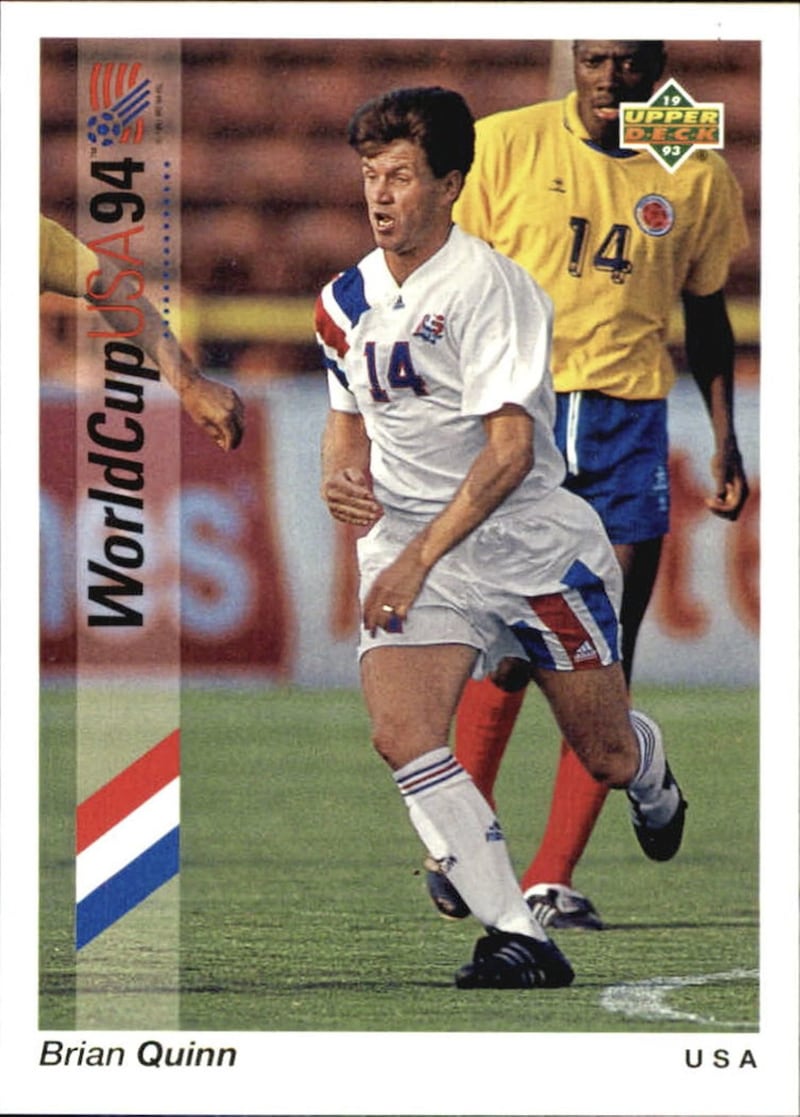

The countdown was on to the 1994 World Cup, the first ever to be held in the States, and a succession of training camps and friendly games were Milutinovic’s only way of arriving at his eventual selection.

In the end, it came down to 28 guys competing for 23 spots when the final call was made. For some, the dream of being part of the greatest show on earth was within touching distance.

For others it was over - including Quinn.

Yet while team-mate Jeff Agoos famously burned his jersey after being told he hadn’t made it, Quinn accepted the decision with good grace.

“The guys I was competing with for two midfield slots were Thomas Dooley, who was our best midfielder, and then Mike Sorber and Mike Burns.

“It’s so emotional at the time when you miss out. I remember having the conversation with Bora and he was in tears but, to be fair, when I look back the starting group was Sorber and Dooley.

“I don’t know if Sorber was any better a player than myself or Mike Burns, but he was a better fit for Dooley. I really believe that.

“I wasn’t bitter. I didn’t want to take anyone else’s dream away. That may sound like an easy thing to say, but that was my thought process within probably five or six hours of finding out.”

After the final friendly against Iceland in April 1994, Quinn didn’t play again.

But he went to every US game at the World Cup, standing proudly for the Star Spangled Banner as they made it out of the group stages before exiting to eventual champions Brazil on Independence Day.

“I loved it – loved every bit of it,” he says.

“The results in 1994 justified everything Bora had done. That team left a footprint in American soccer and I was just happy to have played a small part in that.

“Those are great memories – memories I couldn’t have expected to have, and memories I wouldn’t trade for anything.”