WE’RE right in the middle of storm season, and hurricane Jim has just left the building. Two hours and 20 minutes after arriving at the Balmoral Hotel, he’s away, exiting in a blur of wide smiles and handshakes.

Earlier that day, he had attended a meeting at IFA headquarters. There is another commitment later in the afternoon, then on to Ulster University’s Jordanstown campus that evening to speak at a seminar on sport psychology and mental health.

When he gets back in the door, it’s after 10pm.

All I’ve really done, in contrast, is interview Jim Magilton. Yet it’s me considering trying to cut a deal with the Balmoral to take a room. Just for a couple of hours, until my head stops spinning.

In his playing pomp, Magilton ruled the roost with calm and poise, elegantly dictating the terms of engagement from the comfort of the centre circle.

But off the pitch, the west Belfast man is a force of nature. The restless energy that saw him effortlessly juggle Gaelic football, hurling and soccer commitments throughout his school days still fizzes from him, the buzz of being on the pitch replaced with whatever life throws his way.

Right now, it’s his role as elite performance director with the IFA but, as the top dogs at Windsor Park plan for life after Michael O’Neill - possibly from next month on - Magilton has thrown his hat into the ring.

He was never inhibited when learning his craft at St Oliver Plunkett or when plucking balls from the sky on the top pitch at St Mary’s CBS; the nothing ventured, nothing gained spirit of the brash teenager lives on.

And while the work Magilton has done nurturing the emerging talent at the Northern Ireland academy over the past six years must stand him in good stead when weighing up who best to carry on O’Neill’s magnificent work, so too should a lifetime of sporting experience.

The loss of dad Jimmy almost three years ago was a devastating reminder of how swiftly the rug can be whipped from beneath our feet, and how important it is to grasp every opportunity with both hands.

Time, he was always told, is your best friend. Not just on the pitch, but also in life.

Jimmy’s son is determined that he won’t waste a second.

***************

DREAMS of Liverpool were born in Glencolin Park and lived out in the shadow of the Shankly gates. Dalglish, Souness, Ray Kennedy - Jim Magilton wasn’t short of heroes to try and emulate when he ran out to join friends on the cramped streets around the estate.

The brilliance of those great sides of the late 1970s/early ’80s held a generation in thrall. Magilton was no different. On the freezing cold days in Mallusk wearing the black and white of St Oliver Plunkett, or at Ballyskeagh with Distillery later on, he would imagine it was Anfield he was gracing.

Yet it was another stretch of sacred sod, this one just 100 miles away, that first captured the imagination, his head still stocked with memories of September Sundays spent on brutal roads, and at border checkpoints, en route to Croke Park.

“I was fanatical about GAA.

“You went to any big game you could but the first real big game experience I can remember was the 1982 All-Ireland final when Offaly beat Kerry. Seamus Darby scored that famous goal. It was incredible.”

Soccer and GAA co-existed peacefully in those early days, the seeds of his future career brought to bloom by Jim Denvir and Paddy Lavery at St Oliver Plunkett Primary School before Magilton joined Jackie Maxwell’s revolution at St Oliver Plunkett FC.

“Plunkett had a huge community feel; you were making friends who are still friends now.

“Obviously the Troubles were going on around you, but I just remember being loaded into a green Volvo and heading here, there and everywhere…

“Jackie was a big Liverpool man too so it was pass and move, freedom, never any talk about tactics. Just go and play. As time goes on, you don’t really remember the games, but the laughter never leaves you – and winning. We didn’t lose many games.”

While the majority of his friends and team-mates continued their education at De La Salle, Maureen and Jimmy Magilton decided St Mary’s CBGS – where a ban on entering soccer competitions wasn’t lifted until 2002 - was best for their boy.

“Every day it was either Gaelic or hurling, then I played football whenever I could as well outside of that.

“Eddie McToal was the PE teacher and, right from first year up to sixth, he had a huge influence on me. I’d been at Sarsfield’s from I was a kid with Eddie too so he knew what I was about.

“McToal had built a winning mentality at that school too; we’d had disappointments, lost Corn na nOgs, but it was coming. You could feel it.

“Physically, the GAA brought me on a lot. I played one or two years up - he actually toyed with the idea of having me on the bench for the MacRory Cup final in ’84 when we were beaten by a St Pat’s, Maghera side that had Dermot McNicholl and boys like that.

“The year after that we lost in the semi-final, and the year after was my year.”

Named at full-forward but with license to roam, a 16-year-old Magilton proved the star turn as St Mary’s moved menacingly into the1986 knockout rounds.

The formidable men from Maghera stood in their way once more, eyes fixed on a remarkable fifth MacRory crown in-a-row. But St Mary’s weren’t to be denied - a feat made all the more impressive considering they had to finish the job without their talisman.

By now spending his Saturdays in the white of Distillery, Magilton’s impressive form had earned him a call up for the Northern Ireland schoolboy select; a shop window for top talent to strut their stuff.

One by one, he watched as team-mates were snaffled by scouts from across the water.

Ironically, two of those made to wait a little longer were Magilton and a curly-haired whippet from Ballymena called Michael O’Neill. And when the call did come, it signalled a premature end to his MacRory ambitions.

“I played every minute of every schoolboy game, scored goals, but no-one fancied me. So I stayed and did my O-Levels. From then on MacRory Cup and playing for the Whites, that was everything.

“Eventually a friend of the late, great Jimmy McAlinden came over, a guy called Geoff Twentyman. He’d managed Ballymena in the ’50s and was now chief scout at Liverpool.

“He’d brought the likes of Ian Rush and Alan Hansen in. Thankfully he saw something in me.”

After impressing during a three day trial, Magilton got the call from Liverpool on January 3, 1986.

On New Year’s Day he had played for Sarsfield’s in the final of the Ulster Minor Football Tournament at St Paul’s. Within a week he was cleaning a dressing room filled with men whose faces adorned his bedroom wall.

McToal, though, hadn’t given up on his prized asset just yet.

“He rang Kenny Dalglish, asking could I play in the MacRory final.

“I remember Kenny saying to me ‘there’s some guy McToal’s been ringing me’ and I’m like ‘please no, this guy’s like Liam Neeson in Taken; I will find you, I have a particular set of skills’.”

Magilton rocks back in his seat, sniggering at the memory.

Dalglish, despite McToal’s pleas, didn’t permit the teenage prodigy to play. Twenty-five years later, he eventually received his MacRory medal on a special evening up at St Mary’s. It takes pride of place among all the other accolades collected along the way.

His GAA days now behind him, however, Magilton was setting off to live out those boyhood dreams.

********************

THE first time he had ever left Ireland. The first time he had ever been on a plane. The first time living in digs, away from his family back home.

This is an experience Jim Magilton talks about regularly to the kids at the IFA academy who long to follow in his footsteps. In the late ’80s, there were no mobile phones, there was no FaceTime. No Google Maps.

When you found yourself plunged into deep water you could sink, or you could swim. There was no third option.

“Nothing ever prepares you for it.

“But, for me, so much of the groundwork had been laid in Belfast. I mean, physically I could handle it. Mentally, I was ready for anything. So when I went over to Liverpool, it was just… bring it on.

“At the start I lived on Anfield Road, three doors up from the Shankly gates… you were fending for yourself. You had to get two buses out to Melwood [the club’s training ground], you were in a city you didn’t know.

“But Liverpool couldn’t have been a better fit for me because the people are just so genuine, and they remind you of home. It didn’t take long until I knew the place like the back of my hand, made friends.

“Once they see you can actually play, that gives you a bit of credibility. Life becomes easier then.”

After inking a two-year professional deal the following summer, the club brought Magilton on a tour of Scandinavia, culminating in a friendly against German giants Bayern Munich at the Olympic Stadium. Soon, he was part of Phil Thompson’s reserve team.

And that’s where, for the first time in his sporting career, the shit started to hit the fan.

“For the next year-and-a-half, I was just in a cloud. I got dog’s abuse - ‘you’re a big-time Charlie’, people looking at me. I was in the reserves but I was getting dropped. I was doubting myself.

“Michael O’Neill had just gone to Newcastle and his star was on the rise; I went to watch him at Everton and he was playing with Mirandinha, Peter Beardsley, Gazza. I was thinking I was going to go home and be a plumber like my da, but he wouldn’t hear of it. He kept telling me to stick at it, stick at it, and I turned it around.

“One day Phil Thompson pulled me aside and told me he was making me captain. That was a light-switch moment. You only get recognition at Liverpool if you’re consistent, and I remember walking past Roy Evans in the corridor and him saying ‘you’re doing well’. That meant the world to me.”

With likes of Jan Molby, Steve McMahon and Ronnie Whelan ahead of him in the pecking order, though, it began to feel as though his break would never come – until, at the start of the 1990-91 season, there was a sign that he was getting close.

Dalglish drafted him into the first team squad for the Charity Shield clash with Manchester United. He didn’t get off the bench, but the omens were good.

Or so he thought.

“After the Charity Shield, I saw that as recognition for how I was playing; it felt like a major step. Then one day Kenny came in and I’m thinking, ‘yes, this is it - I’m going to get picked for the first team’. All of a sudden it’s like, how do I get hold of my ma and da to get them over for the game?

“You’re not going to play for the reserves any more,” said Dalglish.

“Okay…”

Here we go, happy days

“We’ve just sold you to Oxford United for £100,000.”

“Wha? Where’s Oxford?”

“Son, you should not be earning £220 a week – you’re 21, this is a living for you,” continued Dalglish.

“You need to start thinking about that. You want to get married, have kids. This is your job - go and get paid for it.”

The shock took a few days to dissipate. Some of his team-mates from the reserves – Nicky Tanner, Mike Marsh, Steve Harkness – would go on to play in front of the Kop, while Magilton was leaving Liverpool with all his worldly belongings chucked into binbags and a piece of paper bearing Dalglish’s scrawl, detailing directions to Oxford.

“I was just praying my car would make it!

“I was there through Hillsborough, I had that identity with the club, I was a Liverpool fan; Liverpool was everything to me. Then to be told you were leaving was devastating.

“The laugh of it is Kenny packed it in about six months later – nice one Kenny, you might’ve given me a heads up!

“Graeme Souness was my manager at Southampton for a year. He came in after Kenny and told me I’d definitely have played in his Liverpool team. Right… thanks for that.”

It seemed as though the walls were closing in around him, but three days after arriving at Oxford – then in the old Second Division - Magilton realised Dalglish couldn’t have been more right.

“I drove up on the Sunday and I played at Upton Park on Tuesday night, under the lights. It was just… I want all of this, again and again.

“This is what people talk about. I left a boys’ club, now it was boom,” he says, slapping the table, “real world.”

Within a year he was captain and top scorer at the Manor Ground, paving the way for a spot at the heart of Billy Bingham’s Northern Ireland team. With friends from the same west Belfast streets already in the fold, running out at Windsor Park didn’t cost Magilton a second’s thought.

“I didn’t have any reservations.

“Mal Donaghy’s mum lived at the bottom of my estate. Anton Rogan lived across the road. They were already playing, and I wanted to do what they were doing. I played alongside Mal in midfield and that was a huge honour.

“Coming up, the natural progression for me was to play schoolboys and then senior for Northern Ireland. There was no other pathway.”

His form for Oxford, and for Northern Ireland, soon started to attract the attention of suitors higher up the league ladder too.

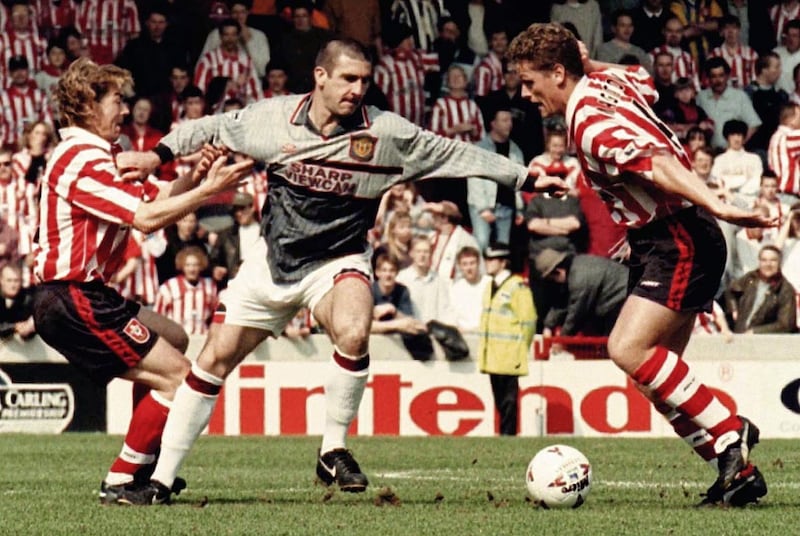

In February 1994 Alan Ball swooped to bring Magilton to Southampton, his Premier League debut - as fate would have it – coming against friends from another time.

“Liverpool at home, Monday night. Matt Le Tissier scores a hat-trick, we won 4-2, and the snow’s coming down in a blizzard.

“The game was a haze, but the thing that stays with me is Ronnie Moran and Roy Evans waiting for me at the bottom of the steps at the end of the game, saying ‘we’re so pleased for you’.

“Even though they’d lost, and losing was never accepted at Liverpool, they took the time to wait for me. That shows the humility of the people, and the club.”

A players’ captain when handed the armband at Saints and then Ipswich Town, Magilton’s next move was already signed and sealed by the time he hung up his boots at 37.

Throughout his career he had kept a journal of things he liked, and didn’t like, about the methods of different managers and coaches. Now a new journey was beginning. And the buck stopped with him.