WHEN David Brady arrived at Molly Fulton’s restaurant a mile outside Sligo, he had never met Mickey Moran before.

2005 had been a frustrating year for the Mayo midfielder-cum-full-back. He and John Maughan didn’t get on and, troubled by a back injury, the pin was ripped out mid-season.

As far as he was concerned, his days chasing Sam Maguire were over.

“The first 25 minutes, we didn’t talk about football,” Brady says, recalling the meeting that winter.

“I had enough done in my mind and body and soul.

“But he was talking about me and life and work. He knew where I worked, he knew about me.

“It was ‘how is the injury and the back?’ It was ‘how are you?’ It wasn’t how are you fixed or do you want to come, it was more ‘do you mind if we talk again?’”

That was Mickey Moran, the players’ man. That strand of his coaching DNA runs right through a sideline career that began at the tender age of 17 with Glen in his native Maghera.

It’s never been more evident than in his relationship with Slaughtneil’s hurling manager Michael McShane as they embarked through a terrain that was hugely rewarding but incredibly tricky to manage.

His relationship with his own club has always been uneasy. He began his coaching career at Watty Graham Park but they hold him to never having managed a club team outright.

Not many would give him credit for any small part in their recently successful underage structures, but if you look hard enough you’ll find them.

For instance, he was responsible for organising a trip up for former Kerry coach Pat O’Shea - who'll be plotting Moran and Slaughtneil's downfall as Dr Crokes' manager ahead of Friday's AIB All-Ireland final - who spent a weekend at the club and whose ideas were lapped up and implemented.

No-one is a prophet in their own land.

Some 47 years on, on the other side of a ragged, argumentative parish border, he enjoys the reverence of a God.

Looking back now it seems remarkable that Slaughtneil had turned him down for the 2013 season as he made a return to football.

A routine check-up had uncovered a triple by-pass in 2011, forcing him to step down from the Leitrim job, where the players had voted overwhelmingly to keep him on for a fourth year.

Recuperated after a complete break, he went for the vacant Slaughtneil job in the hope of lifting them after another county final defeat by Ballinderry, but it was given to Kildress native Cathal Corey.

He could so easily have been the one that got away.

To many observers, he and Slaughtneil were an unlikely partnership.

A mild-mannered, softly-spoken student of the game meets a club that always had the raw hunger to succeed, but at times let it be too raw, and lacked the level-headedness they needed to complement it.

One man in particular saw the merits, though. The late Bernard Kearney had convinced the club to take on John Brennan in 2004, and it paid dividends in the form of their first ever Derry senior football title.

Ten years on, he was one of the primary advocates for hiring Moran.

Since Gerald Bradley flicked home the winning goal in stoppage time at the end of the 2014 county final win over Ballinderry, they’ve won three Derry titles, two Ulsters and now face Dr Crokes in their second All-Ireland final.

Every word that falls from his tongue on the bottom pitch at Emmet Park now is taken as gospel. His presence is manna for a generation that wants so desperately to win, always and everywhere.

He didn’t put the ability in Slaughtneil, but he’s coached the coolness into them.

The patient hand-passing style you see now was characteristic of neither Slaughtneil nor Mickey Moran prior to 2014.

His earlier teams were much more direct.

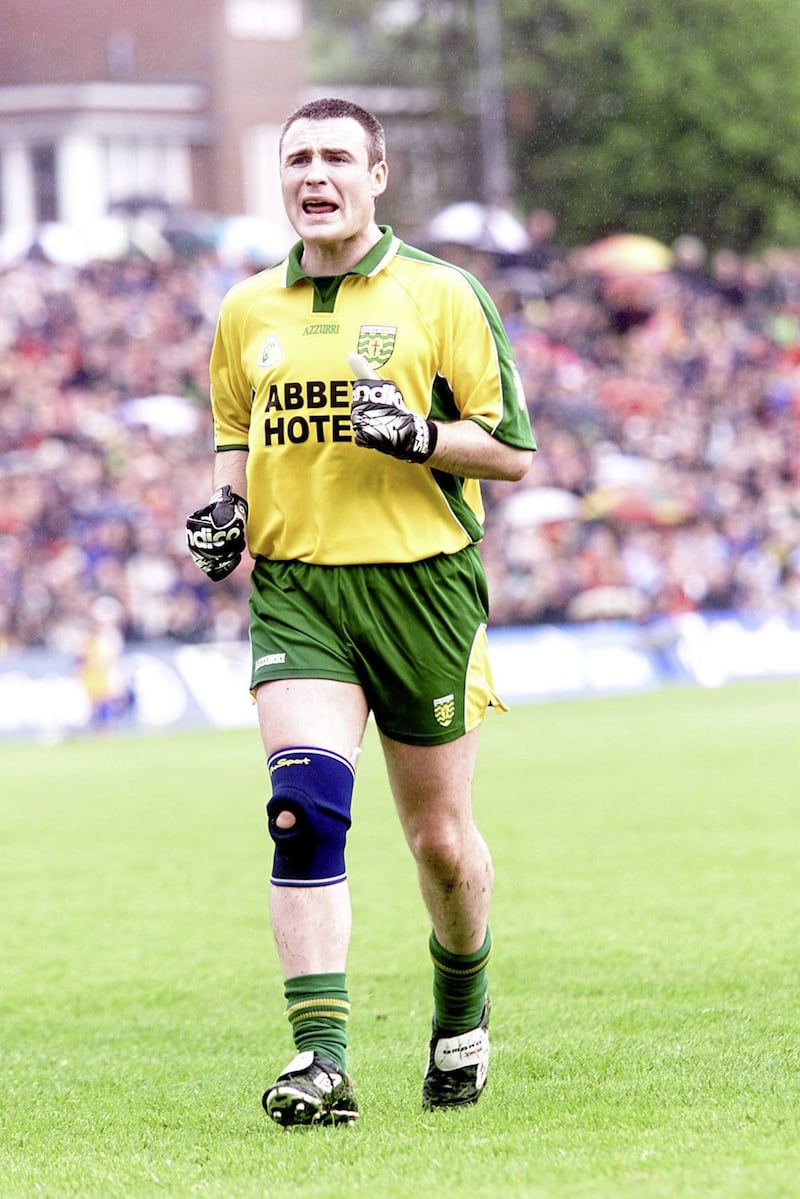

He took Donegal to an All-Ireland quarter-final in 2002 averaging just a point less than the Armagh side that edged them in the Ulster final and went on to lift Sam Maguire.

“A lot of Donegal teams would have been considered good on the ball and comfortable on the ball, but maybe lacked the little bit of directness,” recalls former Tír Chonaill midfielder John Gildea.

“He introduced that directness. He was about keeping the ball to a certain point but then getting it to where you could hurt teams.”

Adrian Sweeney tormented Dublin on a bright Bank Holiday afternoon, but Ray Cosgrove kept the Leinster champions alive, salvaging a replay.

The whole adventure fell apart within hours. Indiscipline was rife among the squad and it reared its head after the game.

Up to half the players didn’t return home on the team bus.

Some made their own way back but the capital’s social scene played host to a sizeable contingent of Donegal footballers for the night.

It had a profound effect on their mental state ahead of the replay. Dublin wiped the floor with them 12 days later.

That was enough for Moran. Many of the players, including Gildea who had returned on the bus, tried to persuade him to reconsider his decision to resign. The Maghera man took two weeks to think about it, and decided he just couldn’t go back.

“He was very disappointed, and he expressed that.

“But given that there were more players that didn’t come back on the bus than those that did, what could he really do?

“It wasn’t like he could drop everyone that didn’t come back on the bus, because we wouldn’t have been able to show up the next day at all, even though to an extent we didn’t show up anyway. He was in a bad position.

“I think that was the moment when he made his mind up, and that was the end of the road for him. He was so disappointed that he took it personally. As a group of players, we let him down and we probably let Donegal down as well.”

As good managers do, though, Mickey Moran learnt the lesson.

Slaughtneil had just cruised through their All-Ireland quarter-final in London back in December when the players got togged in and headed to the rammed clubhouse in Greenford.

With half a squad of tee-totallers it wouldn’t exactly be classed as a problem in Slaughtneil, but the drink was flowing and the craic was good.

It was the first time since August they’d had a clear break without a major Championship game within the next 14 days.

But he brought order and discipline to the situation, entering the bar to whisk the team quickly back to the bus and for the meal, without a flicker of dissent.

Man management, see.

**

NOTHING in his world is done without the ball in hand.

That has been more evident in the last three years than at any time in his coaching career, but the philosophy has been consistent in that regard.

During the days where Morrison was by his side, the trainings varied and were interesting, but the same currant of improving players’ ability on the ball flowed through every single thing their teams did.

“It’s called Gaelic football, not Gaelic running-up-and-down-a-pitch or Gaelic climbing-a-mountain,” reflects Gildea.

“Mickey revolved it all around the skills of the game and how to play it. It was unusual, even in that era.

“What he did was manage to marry the physical intensity that you needed with the skillset you needed to play football. He took the pain out of it to an extent, even though you were working hard. That’s why it was so enjoyable.”

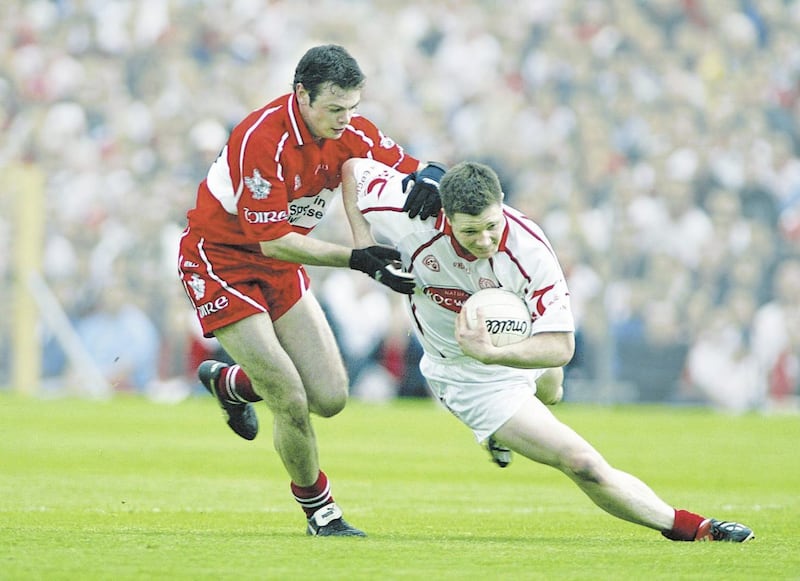

In 2004, Derry unexpectedly reached an All-Ireland semi-final against Kerry by putting Enda Muldoon and Paddy Bradley on the edge of the square and launching everything that reached the halfway line at them.

Excluding the disappointing Ulster Championship defeat to Tyrone, Derry averaged 1-15 a game as they made their way through the back door and disposed of Paidí Ó Sé’s newly crowned Leinster champions Westmeath in the quarter-final.

Moran refereed in-house games and any player that didn’t make a supporting run after he had played the ball was penalised with a free against. The emphasis was very much on attacking.

“Certain managers would have told me my first job was to defend and not to go forward too much,” says Paul McFlynn, who played under Moran during his third spell in charge of Derry from 2003 until 2005.

“Mickey’s big thing was give-and-go. That was getting us into the mindset of attack, attack, attack. We were very offensive.”

And in the manner that his current charges play, that remains evident.

Slaughtneil are exceptionally wise to the art of defending, but they do not play with a sweeper. If the opposition want to play man for man, that’s fine with them.

They like to call their small-sided training games ‘Murderball’.

The aim has changed from the directness of those full-sided games Paul McFlynn loved on the summer evenings of 2004 to emphasising the benefits of keeping possession under severe pressure.

“As a coach and a manager, he’s adapted. He was very clued in to playing to a team’s strengths,” says McFlynn.

“Whatever he had at his disposal, he was a good man for maximising that and making the most out of it. You can see he’s doing that with Slaughtneil at the minute.”

**

“They call it coaching but it is teaching. You do not just tell them…you show them the reasons.”

Vince Lombardi

WHEN he retired as Head of PE in St Mary’s Limavady in 2005 after more than three decades at the school, Moran was freed to build on his love affair with the west coast.

Like every great man, there was a better woman behind him. His wife Rita not only taught for years in St Mary’s Magherafelt, but masterminded the school’s camogie teams, enjoying regular success at Ulster and All-Ireland level.

While Tyrone brought the idea of hunting in packs to the forefront of the national conscience in 2003, Rita Moran had the Convent doing it in the mid-90s.

Her teams tackled in threes and fours and overwhelmed many a more illustrious opposition through sheer workrate.

No surprise, then, that their son Antoin is now part of the backroom team at Emmet Park, having coached alongside his father in Kilrea.

“Rita would tell you she knows more about football and Gaelic games than he does. She’s the brains,” chuckles Gildea, recalling many a phone conversation with Mrs Moran in the days before mobiles.

Having first taken the Derry job in 1980 at the age of 28, Mr Moran was still teaching while he was in charge of Sligo (1996-2000), Donegal (2001-02) and Derry (2003-05).

When he was recommended by a five-man sub-committee to become the first man since Jack O’Shea in 1994 to take Mayo, it came as a surprise.

He and Morrison, a fellow retiree from the classroom, famously trekked to Ballina and back twice and three times a week before taking Sligo the following year and then Leitrim between 2008 and 2011.

Mayo had redefined the boundaries of what was physically possible over the decade previous to his arrival but when Moran came in to replace John Maughan, it was a step in a different direction.

“You’re asking a question of a man here that probably could have competed in the Atlanta Olympics in 1996,” says David Brady.

“What Mickey brought to the table was a whole new world.

“You hear these stories about the Arsene Wengers of the world bringing in new methodology, but we had ball players, we had footballers.

“You probably rarely saw it during the games but you knew in the outcome that it was a vital part of our preparation, that we were so comfortable.”

They took the Connacht title back off Galway in the summer of 2006 but by the time the All-Ireland quarter-final came around against Laois, relations between manager and county board were so strained that the players had to act as intermediaries.

The whole relationship was destined to end quickly, but it briefly threatened to end on the most magical of terms.

Ciarán McDonald’s left foot was a stake through Dublin’s angered hearts in an All-Ireland semi-final best remembered for ‘Hillgate’, when Mayo brazenly warmed up in their hosts’ traditional cocoon.

Moran tried to call the march off.

“He was absolutely incensed,” recalls the former Mayo skipper.

“He was asking ‘who the hell decided this? What do ye think you’re doing? You’ve made your point, let’s go’.

“We were saying the point still had to be made and we weren’t going. Flustered, he was all over the shop! We were saying it was grand. The poor man was perplexed to the highest degree.”

When it passed, the afternoon went down as arguably Moran’s greatest. Seven down to the Dubs with the writing on the wall, his side doubled down to seal a remarkable victory and their place in the All-Ireland final.

He wisely parked his anger at the pre-match shenanigans. The incident was never mentioned to the players again. What sense to make an issue when it worked?

Mayo’s House of Pain was at its most excruciating on the third Sunday in September though, a team completely overwhelmed by occasion and opponent. Kerry strolled to Sam and when it was over, Moran didn’t even get a chance to say goodbye.

“Mickey knew what it took, he knew he needed to express himself and he probably felt restricted. His passion and process got to win out and it was a case of all picture, no sound between the county board and Mickey for weeks and weeks.

“There’s always going to be only one winner in those situations, and it was always that Mickey wasn’t going to be coming back.”

The players knew he was on his way out but the changing room was too dejected for words, and the social scene wasn’t his.

By the time the players finished drowning their sorrows in midweek, the opportunity had passed. Brady hasn’t laid eyes on the man that brought him out of retirement since the third September Sunday of 2006.

But it surprises him very little to see Mickey Moran as successful back on the club circuit as he was when he took Omagh to a Tyrone title back in 1988.

“It resonated so much with Mickey – where we came from was the most important stamp we’d ever have in our lives. Who we represented, the club, was the reason we were in the dressing room with Mayo.

“Going back to All-Ireland final day, going back to our roots and where we were from, each of us was asked individually where we were from, our club.

“We trained and warmed up in our club jerseys because he was adamant that we had a sense of belonging.”