BENNY Tierney was forced to change the habits of a lifetime or run the risk of losing his place in the Armagh team.

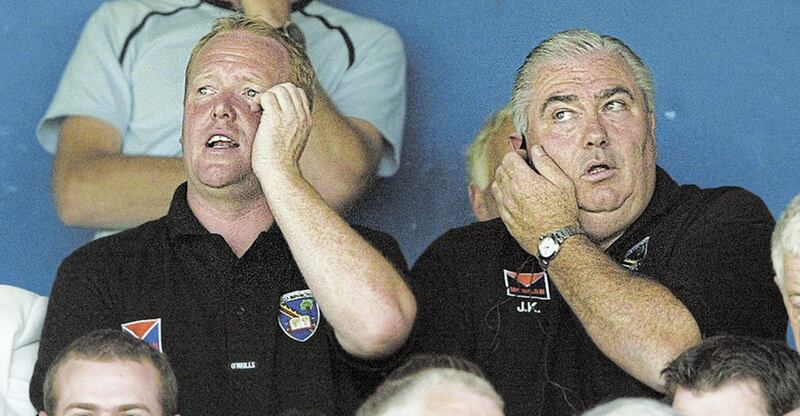

Behind Joe Kernan’s jocular nature, some things were non-negotiable.

His instructions to Tierney were crystal clear.

“I remember Joe said to me that he didn’t want me to be fisting the ball to the McNultys because he felt I’d good feet,” Tierney explains.

“He thought when I got the ball I should be giving 30 or 40-yard passes to Aidan O’Rourke or Andy McCann, who were exceptional half-backs with good feet.

“Our plan was to get the ball as quickly as possible to Marsden and McConville and the boys, which was a great idea because we didn’t want a slow fist-passing game. So he told me: ‘This is what I want you to do...’

“I immediately thought: ‘Jesus.’ For 20-odd years I’d catch the ball under the bar and give a fist pass to my corner-back or full-back.”

In his first game under Armagh’s new management team, Tierney caught the first three balls and fist passed two of them to his corner-backs.

“I said to Joe afterwards: ‘Joe, I f****** forgot to kick it.’ And Joe said: ‘Don’t worry Benny, if it doesn’t happen the next day or the next day after that, sure we’ll just put [Paul] Hearty in.’

“He smiled and I smiled. Message delivered.”

From that point on, Tierney kicked the ball to the flanks. The tactic turned out to be pivotal in beating Kerry in the 2002 All-Ireland final.

With the game on a knife-edge at 1-11 to 0-14, Tierney gained possession.

He aimed for O’Rourke’s flank. Barry ‘Bumpy’ O’Hagan gathered Tierney’s slightly wayward pass and put it into O’Rourke’s path.

Stevie McDonnell darted from his central position, collected O’Rourke’s precise delivery, and fired over Kerry’s bar with his left foot that proved the difference between the sides.

It was typical Armagh. Typical Stevie McDonnell.

After knocking on the door and suffering the pain of the three previous summers, Armagh had reached the Holy Grail.

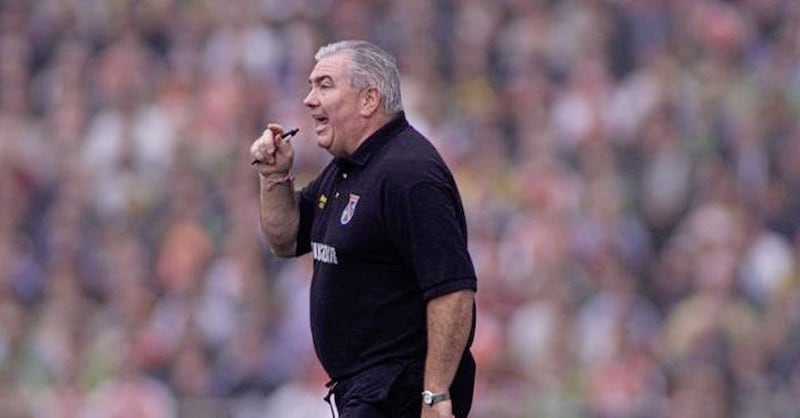

“The intensity of that last 12 minutes at Croke Park was incredible,” says Kernan. “Other Armagh teams would have folded and they didn’t.

“Not one player stepped down in that 12 minutes. That was unbelievable. It seemed like an hour but it proved to me that the boys had made it and deserved it.”

The CityWest Hotel buzzed deep into small hours of Monday morning. Amid all the hugging and back slapping, Tierney vividly remembers Kernan nudging him.

‘I told you,’ said Joe.

‘Told me what?’ asked Tierney.

‘About kicking the ball,’ Joe replied.

“I only caught the ball two or three times in the final and the last time I got it all I could think about was: ‘Don’t fist pass it, don’t fist pass it.’

“I hit a very ropey pass out to Aidan O’Rourke’s wing but it was under Joe’s instructions. It wasn’t a good ball, and you have to remember it was a draw at this stage.

“Joe’s message was simple and I didn’t realise that I’d done it but that was Joe’s plan.

“I see management teams who were defenders and their tactics are defensive with a lot of short hand passing. But Joe and Paul [Grimley] were forwards. I think it was the most forward-thinking, talented Armagh team ever.”

There have been various claims to the genesis of Armagh’s winning template.

The conversation over rightful copyright would include men like Dessie Ryan of Queen’s, while Kernan’s all-conquering

Crossmaglen side were noted for their kicking style.

But a few light brush strokes would also uncover some Meath fingerprints.

But what made it successful in Armagh was the absolute clarity that Kernan and Paul Grimley gave it.

More often than not, O’Rourke and Kieran McGeeney would drop diagonals either side of McDonnell, Marsden, Ronan Clarke or McConville.

Sometimes they would drop it on top of McDonnell and Clarke and their sublime telepathy would do the rest.

“It wasn’t my template,” Kernan insists. “It was what suited our team best. I looked at we had.

“With ‘Cross, I always played a kicking game and I didn’t see any reason to change that.

"But the diagonal ball – that was a Meath thing. Colm O’Rourke and Sean Boylan, they proved that the diagonal ball was the most dangerous ball... but you have to get your players into the positions and you’ve got to know when to do it...

“To me, Aidan’s ball into Stevie was the pass of the Championship. It’s satisfying when those things come off, but you have to have the skill and the confidence to carry it out.”

As with all successful Ulster teams, Armagh assumed the panto villain tag when they headed south over the next four summers.

The entire country was fascinated by the latest, fearsome invention coming out of Ulster.

Everyone wanted a piece of Armagh and they were never off the back pages.

The Irish News kicked up a storm when they got hold of Armagh’s secret red book. The story goes that it was left behind in the changing room and it found its way into the grateful arms of former Irish News journalist Paddy Heaney.

The book of secrets spilled all over the sports pages. The media had a field day.

Sitting in a quiet corner of the Canal Court Hotel in Newry, Joe laughs at the red book ‘scandal’.

“It was much ado about nothing,” he says. “I had to let on I was annoyed at the time. There were no secrets in it. It was just our schedule. I said to Paddy: ‘That’s an old book. You should see the new one we’ve got now!’”

Tyrone, now under new manager Mickey Harte, were sitting on Armagh’s shoulder – but Kernan still had the Orchard County ahead of the chasing pack.

On many levels, Kieran McGeeney’s stoic resistance epitomised Armagh of the early ‘Noughties’.

You ask whether Armagh could have won the All-Ireland without ‘Geezer’, Kernan immediately turns wistful, and pauses.

“Probably not,” he answers.

“‘Geezer’ was your leader. He drove people on. He was the most driven man I ever met, and the boys followed. Every team needs somebody that they’re going to look up to. 'Geezer' was going to put his head on the line, not once, not twice, but every time…”

Many opposition managers would certainly testify to how Armagh’s muscular, no-nonsense approach intimidated them and, in some cases, were already beaten before the start.

“We took in an image consultant. He talked about the way you walked, the way you’d shake somebody’s hand. And those [tight-fitting] jerseys,” Joe smiles.

“They didn’t make us any bigger or stronger. They were made in the V-shape. We weren’t faster or stronger but we looked it. So they were all wee messages.”

With the All-Ireland Qualifier system still in its infancy, it conspired to pit Armagh and Ulster champions Tyrone against one another in the 2003 All-Ireland final.

The all-Ulster clash was undoubtedly the most talked-about final in the history of Gaelic football.

It was impossible to escape the hype.

The Irish News’ annual Ulster Allstars bash at the Armagh City Hotel couldn’t have fallen at a more inconvenient time for the Tyrone and Armagh nominees – just 17 days out from the final.

On the night, the Tyrone players mingled easily - the Armagh contingent not so much.

Kernan and Armagh’s award winners Kieran McGeeney, Aidan O’Rourke, Paul McGrane and Stevie McDonnell (John McEntee was unable to attend) arrived late, sat in the corner of the sprawling function room, picked up their awards and were gone before the night had started.

“In that room that night, we came across badly,” says Kernan, clearly wincing at the memory.

“Sometimes you’ve got to bluff. I thought we made the wrong decision – going in and hiding over in the corner and not mixing.

“I knew what was happening in the room. I thought we lost ground. You’ve got to play the game.

“You’re not going to go over and start hugging [Tyrone] boys that you were going to do battle with a couple of weeks later. They wouldn’t want it and we didn’t want it.

“The bottom line was we were being honoured and we had to respect the people who were there. It was desperate. I didn’t enjoy that night at all.”

Seventeen days later, Tyrone were crowned All-Ireland champions, 0-12 to 0-9.

“Kevin Hughes destroyed us that day,” laments Kernan.

There was no love lost between Armagh and Tyrone.

When the sides met in a National League game in Omagh in March 2003, Tyrone didn’t give the reigning All-Ireland champions a guard of honour.

“I was very disappointed with that,” remembers Kernan.

When it was Armagh’s turn to afford new champions Tyrone the same courtesy – in a 2006 Dr McKenna Cup semi-final at Casement Park - there was initial resistance in the Orchard ranks.

“The reason we did it was because we knew it was the right thing to do,” Kernan says.

“And, do you know what, we gained a lot of respect from Tyrone people.”

The 2005 trilogy with the Red Hands was the ultimate adrenaline rush and will probably never be eclipsed for intensity and sheer drama.

“People don’t give enough credit to those two teams. I remember thinking: ‘Do we have to go through this again?’ But you really wanted to go through it again...

“These were the two greatest teams in their era going head-to-head. Nobody could touch them. There wasn’t a ball won or lost that nobody nearly gave blood for. The whole country was enthralled.”

Did Armagh and Tyrone hate each other?

Kernan replies: “I’d say there was hate there but we had respect for them. Fair play to them, they went on to do something that we didn’t do, and we’ve got to look at ourselves and say why. Was there much between us? A piece of thread.”

Kernan maintains Armagh should have at least won another All-Ireland, maybe two.

“We took our eye off the ball in 2004 against Fermanagh. I heard after the match players were asking were there club matches on the following Sunday, and that wouldn’t have happened a year before or two year before. And we’ll all take the blame…”

Tony McEntee has a different take on one of the most engrossing periods for Ulster football.

“My opinion is that we did well,” McEntee says.

“We won an All-Ireland. We could have got more. If you are talking to Enda McNulty he would say we underachieved. We could have won in ’03, we messed up badly in ’04 and it became a wee bit harder after that.

“In the early days we were much better than Tyrone. In 2003, it could have gone either way. After that, the Armagh team was beginning to age and move on. The Tyrone team was coming strong.

“We competed really well at the top level against good teams over a number of years.”

McEntee adds: “In the early days, with a bit more confidence – and if Joe had been over us earlier – we could have beaten Kerry [in 2000] and won an All-Ireland and we could have beaten Galway [2001] and won that All-Ireland. We did win our

All-Ireland in 2002. It was a toss of a coin between ourselves in Tyrone in ’03.”

“We opened the door for Tyrone,” says Tierney. “I don’t think they would have won an All-Ireland if we hadn’t won one the year before. I went on the Allstars trip and Chris Lawn and [Peter] Canavan were running on a beach because there were five Armagh boys having a Jolly Boys outing. They tried to hide it but I knew what they were at.”

As the summers ticked by, Armagh continued to rage against the dying light.

They were still pocketing Ulster medals but the All-Ireland stage was becoming increasingly difficult to conquer.

Joe wanted to step down after the side’s 2006 All-Ireland quarter-final defeat to Kerry and Grimley was of the same mind.

But, rather than leave a void, he stayed on for one more season before calling it quits.

“It’s harder to manage success than no success,” says Kernan.

“Before you win the All-Ireland nobody seems to be sure and after you win the All-Ireland the whole country knows how to win the All-Ireland. I sort of knew things would change.”

Given the high amount of strong personalities who shared the same space for so long, cracks began to appear in the Armagh changing room.

Compounding their woes was the freakish brilliance of Mickey Harte’s Tyrone side and the painful realisation that a second All-Ireland title was probably beyond them.

“We’d a group of boys that would have done anything for each other but sometimes winning is harder than losing,” Kernan reflects.

“We laughed together, we cried together, we celebrated together, we did all those things. It’s just disappointing we’re not as close. But that happens to teams.”

“In 2002 and 2003, it was great,” says McEntee.

“But after that it wasn’t as straightforward. After ’05 people started re-assessing things: was it Joe or was it the two Brians?

“Some weren’t sure if it was Joe’s success or the two Brians. And, to me, that was absolutely nuts. After all that we’d been through and everything else, it was clear that Joe Kernan got this group across the line.

“When we had our 10-year anniversary we couldn’t all, hand on heart, meet up and agree – and I think that’s a poor reflection on everybody on how it all ended up in Armagh.

“We couldn’t get in a room together and say: ‘Well done everybody – didn’t we have great times?’

“That completely saddens me.”

Kernan encored with the Galway footballers – the birthplace of his late mother – in 2010. He’d planned to give them three years but couldn’t countenance his backroom team being stripped back in his second and third years and so he departed.

“The only problem was Paraic Joyce wasn’t 25 when I took over. He was a genius,” Kernan says.

Eleven years on from leaving the Armagh post Kernan is still motoring along.

His days of patrolling the sidelines are firmly behind him. Nowadays, everything revolves around family, his six grandchildren and the club.

“Patricia and me couldn’t be more proud of our five sons, what they've achieved and how they’ve carried themselves.

“I look back with a lot of fondness on my days with Crossmaglen, Armagh and Ireland," he says.

"With Armagh, the good times certainly outweigh the bad. As manager you have to try to get your backroom team right as well as the squad. I never took in anybody in unless they could improve the team.

“When we won in 2002 everyone did the job they were supposed to do and we all shared in that success.”

The All-Ireland semi-final win over Dublin in ’02 still has a special place in big Joe’s heart.

"Everything froze for those few days after the win over Dublin, and Patricia always said that it was the best day we had because we'd reached the final.

“But when Tony 'Mac' passed the ball to ‘Geezer’ and John Bannon blew the whistle [in the final], no-one can take away my admiration, respect and delight seeing my players fulfilling their potential on one of the greatest days of their lives.”

The Canal Court Hotel is in the middle of its lunch-hour rush. Carvery lunch is on Joe.

Time moves on at a merciless pace. What's known is that the early 'Noughties' were invincible, untouchable days.

Croke Park never felt more alive.

Joe Kernan won all that he could win in the game and his rich legacy will outlive us all.

There was no theatre without Armagh. And no theatre without Joe Kernan.