MERCEDES-BENZ confirmed last week that it had sold one if its most revered cars for €135 million - a sum that not only obliterates all previous records but which also puts it among the 10 most valuable items ever auctioned, writes William Scholes.

The car that persuaded someone to part with van Gogh money was one of just two 300 SLR Uhlenhaut Coupe models in existence.

Built in 1955 and named after Rudolf Uhlenhaut, the genius British-German engineer who masterminded some of the marque's most notable cars, the car was sold at an auction held in the Mercedes-Benz museum in Stuttgart on May 5.

The bidders were handpicked for sharing the "corporate values of Mercedes-Benz" - as well as pockets deeper than the Mariana Trench, presumably - and the proceeds of the sale (that €135m is roughly £115m or $142m) are being used to set-up a global 'Mercedes-Benz Fund' that will provide young people with educational and research scholarships "in the areas of environmental science and decarbonisation".

It is thought that auctioneers RM Sotheby's presented Mercedes with fewer than 10 potential buyers; the successful bidder is rumoured to be a British collector. A condition of the sale is that the new owner will allow their 300 SLR Uhlenhaut Coupe to "remain accessible for public display on special occasions" and that they will maintain it to the same standard as Mercedes - no mean feat.

Any enthusiast will be familiar with the Mercedes 300 SL 'gullwing' but despite looking similar and sporting an almost identical name, it should not be confused with the record-breaking 300 SLR.

The SL was originally a racing car devised by Uhlenhaut in the early 1950s when Mercedes decided to dip its tyres back into motorsport. The gullwing door arrangement was arrived at because the construction of the car's high-sided chassis frame meant conventional doors couldn't be fitted.

It proved highly successful, and Mercedes-Benz's US importer persuaded the company to build a road-going version, complete with a state-of-the-art 3.0-litre fuel-injected six-cylinder engine and four-speed manual gearbox, for his customers. That car was the 300 SL, a landmark car in its own right and highly sought-after today (Former Northern Ireland prime minister Terence O'Neill owned one; his example sold for $1.375m in 2015).

Appetite whetted by the (racing) 300 SL's success, Mercedes wanted more, and gave the green light for a proper return to Formula 1. It also wanted to consolidate its successes in sports car racing.

A plan to debut two new racers for the 1954 season was hatched. The Formula 1 car - dubbed the W196 - took priority and the road racing version - the 300 SLR - wasn't ready to compete until 1955.

The two cars essentially shared a chassis and the same awesome eight-cylinder fuel-injected engine, five-speed gearbox and suspension. Because of different regulations in Formula 1 and sports car racing, the W196 had a 2.5-litre engine, with the 300 SLR bored out to 3.0 litres. The W196 was a single-seater 'monoposto', with the 300 SLR modified to accommodate two-abreast.

The W196 was an outstanding racing car - Juan Manuel Fangio won the Formula 1 drivers' championships in 1954 and 1955 in it - but the 300 SLR was exceptional.

It raced only in the 1955 season, debuting at the Mille Miglia where Stirling Moss wrote both his own name and that of the SLR into motorsport mythology, with a drive many regard as the greatest ever. Moss averaged nearly 100mph over the race's 990 miles on twisty Italian roads...

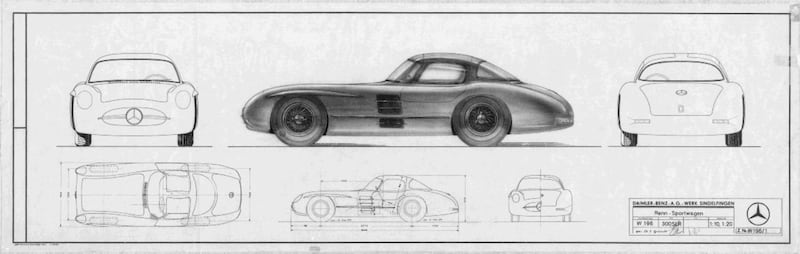

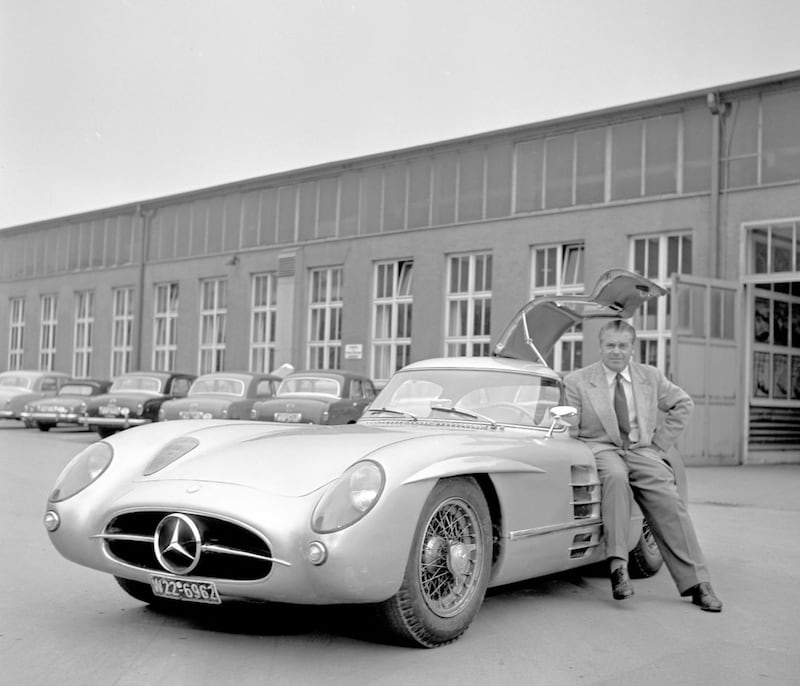

Meanwhile, as a further refinement of the 300 SLR concept, Uhlenhaut - who was in charge of the development programme - wondered if a closed-roof Coupe would be even faster... thus, two of the nine chassis were set aside to be built as an SLR with bodywork inspired by the 300 SL. The finished car became known as the 300 SLR Uhlenhaut Coupe.

Which brings us to the silver car on these pages; but what is it about it that has persuaded someone to part with a sum so extraordinary even Croesus would hesitate?

Rarity, provenance, the link to the 'Silver Arrows' racing cars of the 1950s - an era when Fangio, Moss and other legends drove these cars - and the direct connection with Uhlenhaut are obvious factors.

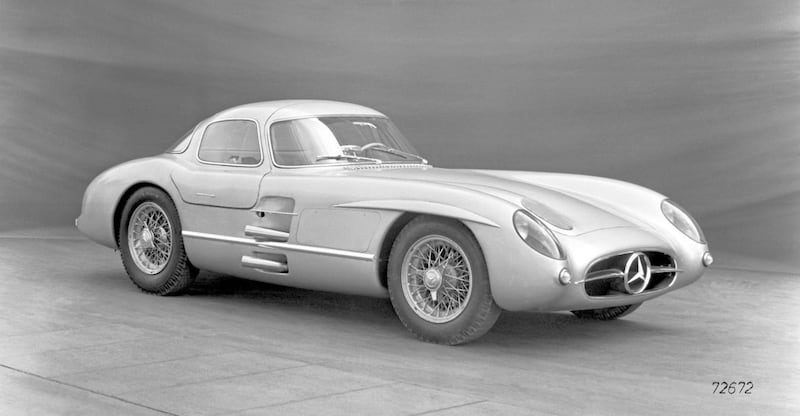

So too is the jewel-like engineering and the sheer beauty of the car, a symphony of sleek magnesium bodywork, gullwing doors and an exhaust note that sounds like the straight-eight-cylinder racing engine has ingested Wagner's Ring Cycle.

It was emphatically and definitively the fastest road car of its era too, capable of topping 180mph at a time when a contemporary Volkswagen Beetle or Morris Minor would have called it quits before 60mph. Famously, Uhlenhaut is on one occasion reputed to have made the 140-mile trip from Munich to Stuttgart in just over an hour...

But what probably really supercharged the Uhlenhaut's value is the fact that the very idea that Mercedes would ever sell either of the cars was supposedly unthinkable. In getting their hands on one of the 300 SLR Uhlenhaut Coupes, the buyer has in effect secured the unobtainable.

Cars of this sort are often referred to by their chassis number. The car Mercedes has parted with is chassis number 8 and it is sobering to think that number 7, which it retains, would likely be even more valuable (making Moss's Mille Miglia-winning 300 SL perhaps the most valuable car of all?).

Number 7 was used extensively in late summer 1955 as a sort of test and reconnaissance car, with Uhlenhaut using it to drive from Mercedes HQ at Stuttgart to attend Grands Prix at Kristenstad in Sweden and Monza in Italy. At both venues, the car completed hundreds of miles on track, performing with faultless reliability for the race drivers, before Uhlenhaut hopped in and drove it back home.

At the time, one of the most prestigious road races in Europe - along with events like the Mille Miglia and Targa Florio in Italy - was the RAC Tourist Trophy race, then hosted at the Dundrod circuit in Co Antrim.

Herein lies the 300 SLR Coupe's connection with Northern Ireland. To help the Mercedes team's effort ahead of the 1955 TT race, number 7 was dispatched from Germany to Dundrod, a 2,456-mile round trip.

Once at the circuit, Fangio, Moss, Karl Kling and the ubiquitous Uhlenhaut completed 222 practice miles as they familiarised themselves with the idiosyncrasies of the 7.4-mile route.

Moss and his partner John Fitch won the race, with the two sister Mercedes 300 SLR - the open-cabin racers, as opposed to the Coupe - cars of Fangio/Kling and Wolfgang von Trips/Andre Simon coming second and third respectively.

To help the Mercedes effort ahead of the 1955 RAC Tourist Trophy race, a 300 SLR Coupe was dispatched from Germany to Dundrod, a 2,456-mile round trip. Once at the Co Antrim circuit, Juan Manuel Fangio and Stirling Moss piled on the practice miles as they familiarised themselves with the idiosyncrasies of the 7.4-mile route.

Three competitors died in the race, spelling the end of car racing at Dundrod. But it was only the latest tragic chapter in a summer that had already been shattered by what remains the most deadly crash in motorsport - the Le Mans catastrophe which killed French driver Pierre Levegh and 83 spectators, with 180 injured.

Levegh was driving a 300 SLR when the accident happened and the disaster prompted much soul-searching at Mercedes, which decided to pull out of motorsport at the end of the season. It didn't officially return to competition until 1989.

Thus the Uhlenhaut Coupe never got a chance to enter the races it had been designed to dominate. Instead, at the end of the 1955, number 7 was adopted by Uhlenhaut as his road car and a second Coupe built on chassis number 8.

Aside from the hard miles clocked up by number 7 going to and from Europe's race circuits, the only differences between the two Coupes were their interiors; number 7 has an interior trimmed with blue leather, whereas number 8 is finished in red.

Both are utterly stunning and captivating. But the Uhlenhaut comes with a health warning: it is incredibly and inescapably noisy. The car could be heard, it was said at the time, from 5km away. Uhlenhaut always wore earplugs when he drove the car; nonetheless in later life he suffered hearing loss, which was blamed on the din of the engine.

Where the noise could dissipate in the open-air Formula 1 and 300 SLR cars, it was trapped within the cabin of the Coupe. Similarly, excess heat from the engine flooded the cabin.

Perhaps Uhlenhaut drove everywhere so quickly because he was trying to escape the torture meted out from within the car that bore his name - but what a car...