RALPH Erskine was a renowned historian of cryptology who lifted the veil on the secret world of codebreaking long before it was popularised by Hollywood.

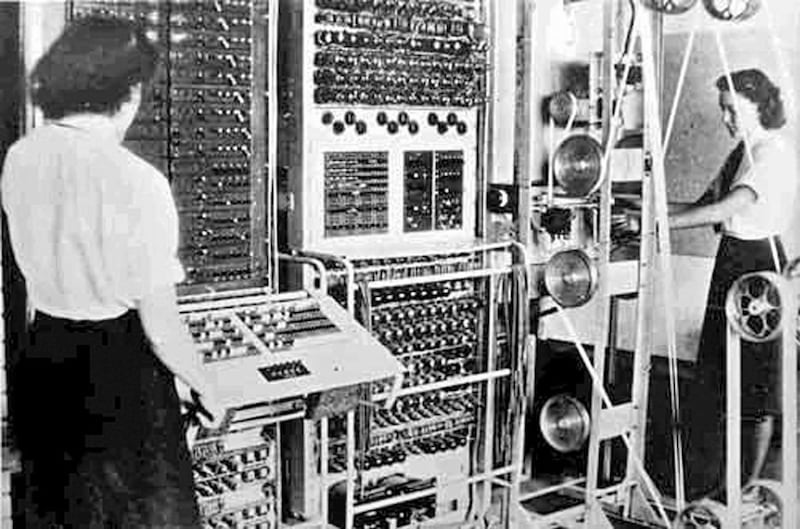

He was the world's foremost authority on Bletchley Park, where efforts to decipher the German Enigma machine are credited with saving millions of lives in the Second World War.

However, much of this scholarship was done in retirement, after a career in which he had made his own important but also largely secretive contribution to the pursuit of peace in Northern Ireland.

As permanent secretary of the Northern Ireland Office at the height of the Troubles, he took the lead in drafting all legislation for the region during two decades of direct rule.

"Everything he did was for the people of Ireland and Northern Ireland," his son Paul said.

"So many lives were lost in the Troubles and he really wanted to help bring people together.

"Hardly anyone outside the civil service would have known his name but he dedicated himself to helping society."

Thomas Ralph Erskine was born in Belfast in 1933, the second of four children to baker Robert Erskine and his wife Mary.

He was a talented pupil at Portora Royal School in Enniskillen and Campbell College, Belfast, although his education was interrupted when he contracted TB and spent 18 months in hospital.

Having studied law at Queen’s University Belfast, he finished first in the UK Bar finals but never practised in the courts.

Instead, following the call of John F Kennedy for the best and brightest to contribute to public service, he joined the Northern Ireland civil service and applied his considerable intellect to the forensic task of drafting legislation.

After the imposition of direct rule in 1972 he was seconded to Whitehall, although he returned home after a year when the air quality caused his son to suffer asthma attacks.

A decade later he was involved in preparing legislation for the Anglo-Irish Agreement, hated by unionists for giving the Irish government a say in Northern Ireland affairs.

It was also around this time that police descended one evening on his Hawthornden Road home near Stormont to warn him it was being staked out as part of an IRA plot to assassinate him.

"He was targeted because of his legal work," Paul said.

"I came home from college to find heavily-armed RUC men at the house and we had to move out that night."

The family moved to Comber and adopted their mother's maiden name, Palmer. Ralph's role at the NIO was thereafter described as 'first legislative counsel'.

However, he always remained unfailingly modest about his work and the risks involved.

And despite wanting to continue working beyond the official retirement age, he stepped down more than five years early to free up opportunities for others.

In retirement he could devote more time to his passion for cryptology, pouring over documents in the National Archives at Kew and contributing to many academic journals and conferences.

He was also a visiting research scholar at the Bletchley Park Trust and co-editor with Michael Smith of Action This Day (2001), an acclaimed series of essays on subjects ranging from the breaking of the Enigma to the birth of modern computing.

Historians, film-makers and authors often sought out his expertise. Military historian Max Hastings said: “Every historian of the Second World War and student of cryptology owes him a debt for his extraordinary contribution to the scholarship.”

Ralph was also a keen skier and yachtsman and in later years took up gliding, a sport he introduced to disabled people.

He died aged 87 on April 9 and is survived by his wife Joan and children Diane and Paul.