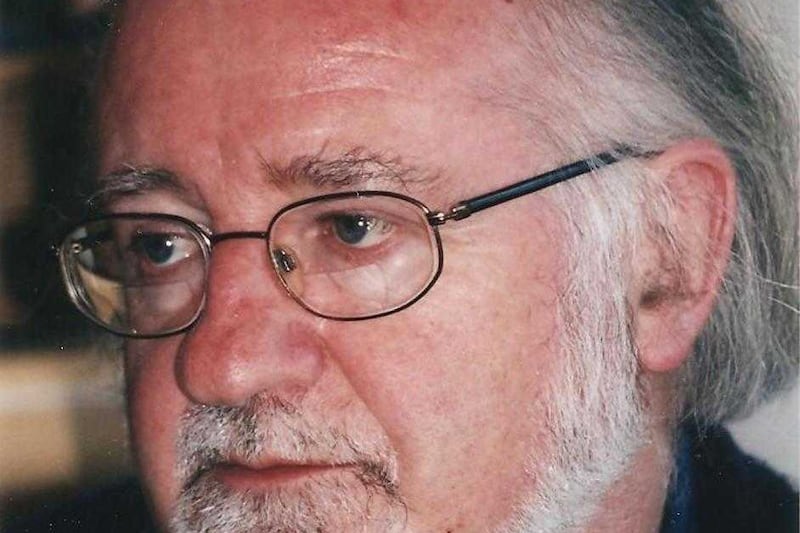

JOHN F Deane grew up on the incredibly picturesque Achill Island on the west coast of Ireland, so it’s hardly a surprise that he felt moved to start writing poetry.

Not only did he go on to become a renowned poet, but Deane founded the Poetry Ireland organisation in 1978 and its journal The Poetry Ireland Review.

The Mayo man's current book, Give Dust a Tongue, features plenty of his poetry but it is essentially a memoir, taking us back to his birth in Castlebar in 1943, his schooldays in Bunnacurry on Achill to the present day and taking in the untimely death of his brother Declan, a Jesuit priest, almost five years ago.

Raised in a strictly Catholic upbringing on Achill, Deane doesn't identify as a Catholic now but as a Christian. In Give Dust a Tongue, he writes that, “It irritates me that ‘atheists’ are basically encouraged to announce their atheism with a certain panache, but to be a ‘Christian’ writer, or to mention God or Jesus in a poem, draws some opprobrium.”

He felt so strongly about a negative newspaper review of his book that he devoted his lecture at the John Hewitt Summer School in Armagh in July to the critic.

“The book has the subtitle A Faith and Poetry Memoir and it covers how I came to the faith that I’m working towards and how I joined faith and poetry together,” he explains.

“In the review the reviewer complained that I was 'too Christian for my own good’ and that – as deeply involved in poetry as I am – I didn’t point out any secrets and I wasn’t indiscreet in any way. I couldn’t let that go, so that became the subject for my talk: 'Too Christian for his own good’.”

He says he wanted both in his book and in his lecture to clarify what he means by 'faith' and to distinguish it from church, dogmas and doctrine.

“I was brought up in a very traditional Roman Catholic environment. Over the years I’ve been trying to figure out what that [the Catholic faith] was all about and if there was anything of value in it that I could retain.

“I find that the way that I discover the world most clearly is through poetry – my own and other people’s. In my talk I mention some of the great poets of our time who are Christian poets and then I take Seamus Heaney, who declared himself an agnostic at the end of his life, and [Dublin poet] Thomas Kinsella, who more or less has the same view.

“I try to point out that there is a basis of Christian faith in all of these writers. I quote both Heaney and Kinsella to show that, although on the surface they reject religion, deep down there is a faith and a holding on to something.

“Seamus came out and said he hadn’t a belief in anything. But there’s a way that you can go beyond belief into your own inner sanctum. I think both Seamus's and Thomas’s poems have that.”

Deane even got Heaney to write a poem for an edition of the Poetry Ireland Review a couple of years ago.

“I came up with the idea of asking poets to write a personal response to the person of Jesus Christ. I spoke to Seamus and his reply was, 'I will certainly keep it in mind and have a go’. He was unwell at the time and he said he hadn’t written a poem in a long time. I met him later at a party and he said, 'I have something for you’. He sent it to me and I thought it was absolutely beautiful.

“So I published it and I quote that poem in my talk. He told me that the poem got him writing again.”

If Deane already had some issues with the ways of the Catholic Church as he grew up, he agrees that the countless scandals that have rocked the Church in the past couple of decades have done huge damage to its reputation – despite the emergence of refreshing reformer Pope Francis.

“When the whole Catholic thing lost a lot of its hold and its meaning over the past few decades, it stopped developing and it didn’t keep up with its people,” he says.

“Now the new Pope has become an ecologist and everything else, but all of that should have been happening decades ago. So many things in the Catholic Church have been so negative.

“There are so many beautiful things in Christianity, but sticking rigidly to a set of rules and regulations as you go along means that the world passes you by.”

He says he attends the Redemptorists’ church in Dublin. The religious congregation of brothers – mostly Catholic – was formed in Italy in 1732.

“I relish the sermons that you get and there’s a great sense of community too,” he says. “I find them quite progressive. And then they have the wonderful Clonard Monastery in Belfast.

“So I would call myself a Christian. To me, if there’s any belief at all and if there is a God, there’s only one God. We approach it in different ways but we shouldn’t say 'My way is better than your way’. We’re all searching for the same thing.”

:: Give Dust a Tongue is out now, published by Columba Press.