IT WAS the dead kid scratching at the bedroom window that did it for me. There were plenty of other moments of shorts-soiling potential in Salem’s Lot, of course. There’s that Nosferatu-channelling vampire at the story's core, for a start – that bald pate, blazing neon eyeballs and bloody fangs can do strange things to an impressionable youth.

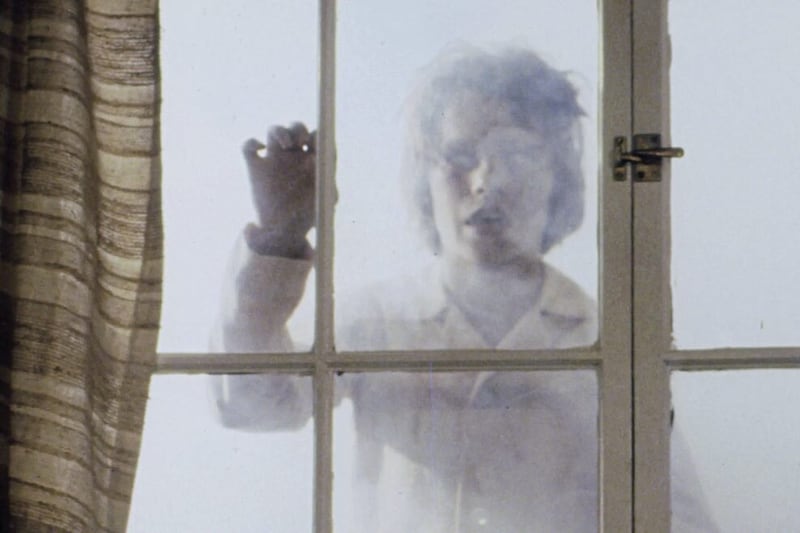

But it was that image of the little boy with the fixed grin floating malevolently at the window in a cloud of billowing smoke, tapping repeatedly at the glass in the hope that his living friend might just let him in that left me well and truly traumatised when I first saw it in 1979.

I couldn’t rest at night until I’d checked the bedroom window several times.

Such is the power of director Tobe Hooper’s made-for-telly adaptation of Stephen King’s 1975 novel I can still recall entire sequences almost shot for shot. Hooper, who passed away this week at the age of 74, just knew intrinsically how to push the buttons for horror-hungry youngsters, I suppose.

His films were a huge part of my early film-loving life. From his 1974 calling card The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, a film that genuinely changed the face (and torso) of modern horror, to his 1982 supernatural thriller Poltergeist and that classic TV serial take on Salem’s Lot, he could do no wrong in my book.

He was a storyteller who understood that kids want to be scared and that being creative with the gore and peppering proceedings with a dash of dark humour was what it was all about.

A proud Texan, he knew his film history better than most and you can see and feel his real love for the genre in those formative productions. It’s a shame then that he’ll likely be best remembered for the controversy that arose from his goriest on-screen moments.

Take the outrage and ill-informed anger that surrounded his most famous creation, for example. What the Mary Whitehouse brigade who lambasted Texas Chainsaw Massacre failed to grasp was the classic structure at the core of that simple tale of inbred cannibals who feast upon the unfortunate city folk passing through their patch.

It was cheap and cheerful, for sure, but it was a traditional scary story that played out as predictably as any old gothic folk tale and in the central character of Leatherface, the chainsaw-wielding weirdo providing for his family’s unusual needs, it gave us one of the true great icons of horror cinema.

That passion for visceral thrills and traditional B-movie plotting is also there in the bigger-budget, more mainstream success of Poltergeist and even in less appreciated offerings like The Funhouse or Lifeforce.

Although Hooper continued to make movies until 2013, like many a cult king, it’s his earliest efforts that he’ll be remembered for.

Rewatch Leatherface fire up that chainsaw or wait for those jumps in Salem’s Lot and shiver along with all those 70s teenagers whose lives were changed forever when they first saw them.

Which reminds me – isn’t it about time I checked those window locks?