ACTRESS Sally Field has taken a long time to write her life story – seven years of soul-searching, delving into her deepest, darkest memories of the people, places and events that have framed the person she is now.

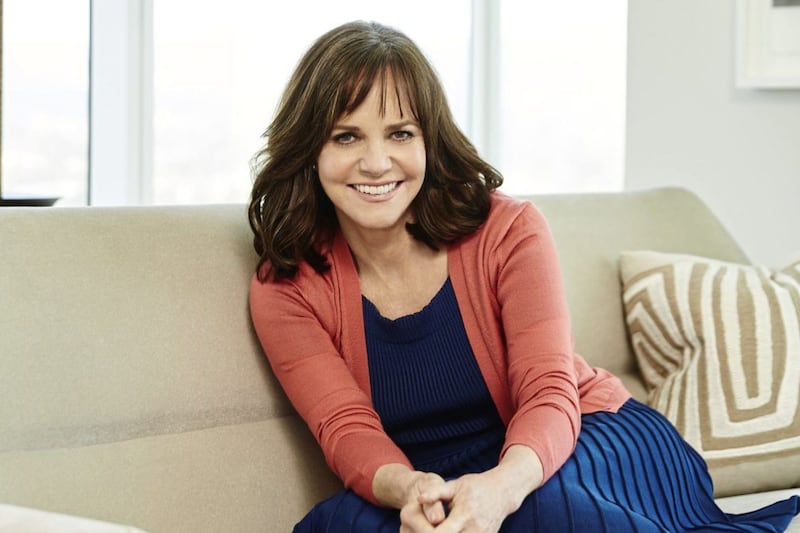

Meeting her today, at 71, she still has the same familiar elfin looks, petite physique and warm smile that have served her well over the years – from her early days of American TV starring in the bizarre series The Flying Nun, to her Oscar-winning performance in 1979's Norma Rae (about a factory worker-turned-union activist), and portrayal of Mary Todd Lincoln opposite Daniel Day-Lewis in 2012's Lincoln.

In Pieces is no celebrity memoir, however. Her box-office successes in films including Mrs Doubtfire, Forrest Gump and Steel Magnolias are skimmed over in a few lines, while her three-year relationship with Burt Reynolds – whom she paints as a controlling force – makes barely three chapters.

She met him in 1976, when he requested she starred with him in Smokey And The Bandit, by which time the weight of his stardom had become a way for him to control everyone around him, she reflects.

"We were a perfect match of flaws," she writes. "Blindly I fell into a rut that had long ago formed in my road."

But the anchor in the book is her complex, loving and troubled relationship with her mother Margaret, whom she called Baa, an actress who divorced her father Dick when Sally was three and then married a stuntman, Jocko Mahoney, who sexually abused Sally from the age of seven to 14.

"My whole book is about my trying to understand and unweave the survival mechanisms that I set in place as a child and how sometimes they disallowed me from seeing what was really present," she says now.

Acting helped her find her voice, but there were many struggles along the way – an abortion at 17, depression, loneliness, self-doubt in her career, as well as two failed marriages and the therapy she needed to talk frankly to her terminally ill mother about her stepfather before she died.

She started the memoir after her mother's death seven years ago, on Field's 65th birthday; November 6 2011.

"After she was gone, I felt deeply disquieted. It wasn't just grief, there was something missing. I felt like I had a malignancy, something gangrenous growing on me and I didn't know why I felt this way.

"I had to find a way to dig out all the pieces that I had hidden away both in my mind and in boxes of memorabilia that I'd never been willing to look at, that I didn't want to see."

When her mother left her father, she took Field and her older brother Ricky to live with their grandmother Joy, born of a generation of women who were expected to put their own needs second to the desires of the men around them.

Many of the men Field writes about, both professionally and personally, are controlling.

Margaret married Mahoney in 1952 – and had Sally's half-sister Princess six months later – and when the abuse started, her survival mechanisms kicked in further as she withdrew. The abuse undoubtedly affected her relationships with men as she grew older.

"My survival mechanisms affected every part of my life and certainly affected my ability to see men. I was used to being treated a certain way by my stepfather and so when those patterns would repeat themselves, they were like pre-formed ruts in my road.

"There were times in my life when I could have said, 'I don't like this behaviour, I'm gone, goodbye', but systems were already set into place. I didn't have a choice, I didn't see a choice.

"My stepfather was adoring me, he held me all the time, yet I was terrified," she continues. "For the rest of my life, it meant that to feel really loved you also have to feel terrified. It's very hard to detangle that."

Margaret later divorced Jocko but so much had been left unsaid that the disconnection between mother and daughter continued, even though Margaret was there for Field whenever she needed her, looking after her three children when she was on location filming, supporting her both emotionally and professionally.

Field, who now lives alone in the Pacific Palisades, an up-market neighbourhood on the Los Angeles coast, began her book long before the #MeToo campaign was even thought of, yet had herself been the subject of unwanted advances.

She claims that one director asked her to remove her top so he could see her breasts as there was a nude scene in the film. She complied. When she had put her top back on, he said the part was hers if she kissed him. She complied. "I had won the role, yes. But I had lost something important, something I was also fighting for: My dignity," she writes.

"I had some episodes that were egregious," she says now. "The only reason I wrote about them was because they affected me and imprinted on my life."

Does she think the movie industry has moved on?

"It's not just the movie industry, it's every single industry in the world, where men and women work together, it's just the movie industry is more visible. This is the way society has been acting always and in some cultures, it's a hell of a lot worse.

"But if the motion picture industry is more visible, and it's used in that visible way to make the outrage more palpable, then that's a good thing.

"But on the other side of the outrage – which I completely applaud and for which I'm grateful – there has to be something else. We have to work out how we move society forward, not only so that women feel they have choices and men don't behave in criminal ways or are just jerks.

"One of the great things is that women are running for office. Things will be different if women are in the front office of every single industry."

The book reaches an emotional conclusion when mother and daughter finally find a way to talk about the parts of their lives which had remained unsaid, and created barriers in their relationship. This happened when Margaret was dying of cancer, and Field had found a therapist who could open those long-closed avenues of communication.

"My mother was dying, I felt like I was dying, we were living in the same house yet I didn't want to run into her, at the same time Lincoln was brewing and the part of my brain was saying I wasn't going to get to do it. The therapist was instrumental during this time."

It turned out that her mother knew of a singular act of abuse which Jocko confessed to her and which, ultimately, contributed to their divorce. She was shocked to hear that the abuse had actually continued through her daughter's adolescence, but assured her that she wouldn't be alone any longer in her pain.

"She was my devoted, perfectly imperfect mother. I loved her profoundly and I will miss her every day of my life," Field concludes.

:: In Pieces by Sally Field is published by Simon & Schuster, priced £20.