ONE hundred years ago this month, the Ulster Unionist leader Edward Carson used his Twelfth of July speech to 25,000 Orangemen at a field in Finaghy to deliver an incendiary message: "We must proclaim today clearly that come what will and be the consequences what they may, we in Ulster will tolerate no Sinn Féin – no Sinn Féin organisation, no Sinn Féin methods… And these are not mere words. I hate words without action."

By 1920, the war in the south and the west of Ireland had started to reach Ulster.

On top of sectarian violence in Derry, where nearly 40 people were killed in two months, there were many IRA attacks on RIC barracks in Monaghan, Cavan, Armagh, Tyrone and Down. Ambushes on railways in Ulster were becoming almost daily occurrences.

During Easter 1920, the IRA Belfast Brigade took part in a countrywide campaign of arson attacks on tax offices to mark the anniversary of the 1916 Rising. The increased activity in Ulster led to Carson's claims of a Sinn Féin "invasion of Ulster".

Whilst unionist fears of Sinn Féin were genuine, the IRA was far weaker both in membership and arms numbers in the north-east than anywhere else on the island. Although the Ulster Volunteer Force had not been active between 1914 and 1919, its members still retained their weapons, substantially more than the IRA had at hand.

Days after Carson's Twelfth of July speech, the RIC divisional commissioner of Munster, Gerard Smyth, a native of Banbridge in Co Down, was killed by the IRA in Cork. His death and funeral were the catalysts for the violence that spread to Belfast in late July 1920.

After his burial in Banbridge, local Catholics and their property were viciously attacked as well as in nearby Dromore and Lisburn, with many Catholics chased from their jobs with their homes burned. The violence then spread to Belfast.

Returning from the Twelfth of July holiday on July 21, shipyard workers were greeted to notices calling for a meeting of 'all Unionist and Protestant workers' during the lunch-hour outside Workman Clark's yard that day. The meeting called for the expulsion of all 'non-loyal' workers from the shipyards.

Straight afterwards, a mob went on a rampage looking for potential victims. Some workers, fearing the worst, left before lunchtime. Some, more unfortunate workers, were stripped to their undergarments in a search for Catholic emblems such as rosary beads.

Many were severely beaten. Others, whilst swimming to safety across the Musgrave Channel were struck by 'shipyard confetti' of iron nuts, bolts, ship rivets and pieces of sharp steel.

Catholics were soon expelled from many other employers in the city. According to the Catholic Protection Committee, a total of 10,000 men and 1,000 women workers were expelled, about 10 per cent of the nationalist population of Belfast. Protestant socialists ('rotten prods') were also expelled from their jobs. During the two years of the intense sectarian violence in Belfast from 1920 to 1922, over 1,000 Protestants were forced out of their homes too.

The unrest travelled from the workplace to the streets of Belfast, resulting in nineteen dead and many more wounded or homeless within five days. Retaliation from the Catholic community was not long in coming, provoking yet more retribution from the loyalists.

Another wave of violence started after the death of RIC District Inspector Oswald Swanzy in Lisburn in August. Swanzy was believed to have been involved in the killing of Cork Lord Mayor, Thomas MacCurtain in March 1920, making him a prime target of the IRA. He was shot dead on August 22 as he left a church service in Lisburn. The loyalist reaction led to the expulsion of almost the entire Lisburn Catholic population from their homes. 300 homes were destroyed.

Catholic families fleeing Lisburn took trains to Belfast or Newry. Many had to walk to Belfast, crossing the Divis Mountain en route. The rioting spread to Belfast, where 22 people were killed in just five days. On August 30, the military authorities brought in a curfew from 10.30pm to 5am for the Belfast area. It was to last, with variations in the times, until 1924.

The sectarian violence that started in July 1920 engulfed the six counties in waves for the next two years. It is estimated that over 550 people were killed violently in the six counties during this period. Approximately 300 of the dead were Catholics, over 170 were Protestants and over 80 were members of the security forces. Belfast accounted for the vast bulk of the deaths with just under 460, as well as over 1,100 people wounded. Catholics, with one quarter of the population of Belfast, suffered over 70 per cent of the deaths in the city.

Catholic relief organisations estimated that in Belfast between 8,700 and 11,000 Catholics were driven out of their jobs, 23,000 Catholics were forced out of their homes and that about 500 Catholic-owned businesses were destroyed. Those forced from their homes had to seek refuge elsewhere, in places such as Dundalk, Dublin and Glasgow.

The nationalist community considered the period as the 'Belfast pogrom', where Orange mobs and regular and auxiliary members of the police force carried out this campaign of terror. Unionists saw it differently. They saw the threat posed by the IRA, the disorder it had caused in the south and west of Ireland, and were determined to prevent the contagion spreading to the north. They were deeply distrustful of Dublin Castle and of the mainly Catholic police force, the RIC. They took matters into their own hands and armed themselves.

They also were successful in lobbying the British government to establish their own police force, the Ulster Special Constabulary in late 1920. By early 1922, one in six Protestant males of Northern Ireland were members of the Specials.

So many people were impacted deeply by the sectarian violence that came with the birth of Northern Ireland, from both communities. That the Catholic community suffered more, there can be no doubt. Judging by the scale of deaths, wounded, evictions and homes and businesses burned, the Catholic community bore the brunt of the violence.

Although a stability of sorts was achieved in the north by 1923, it was done so in what remained a deeply bitter and divided society.

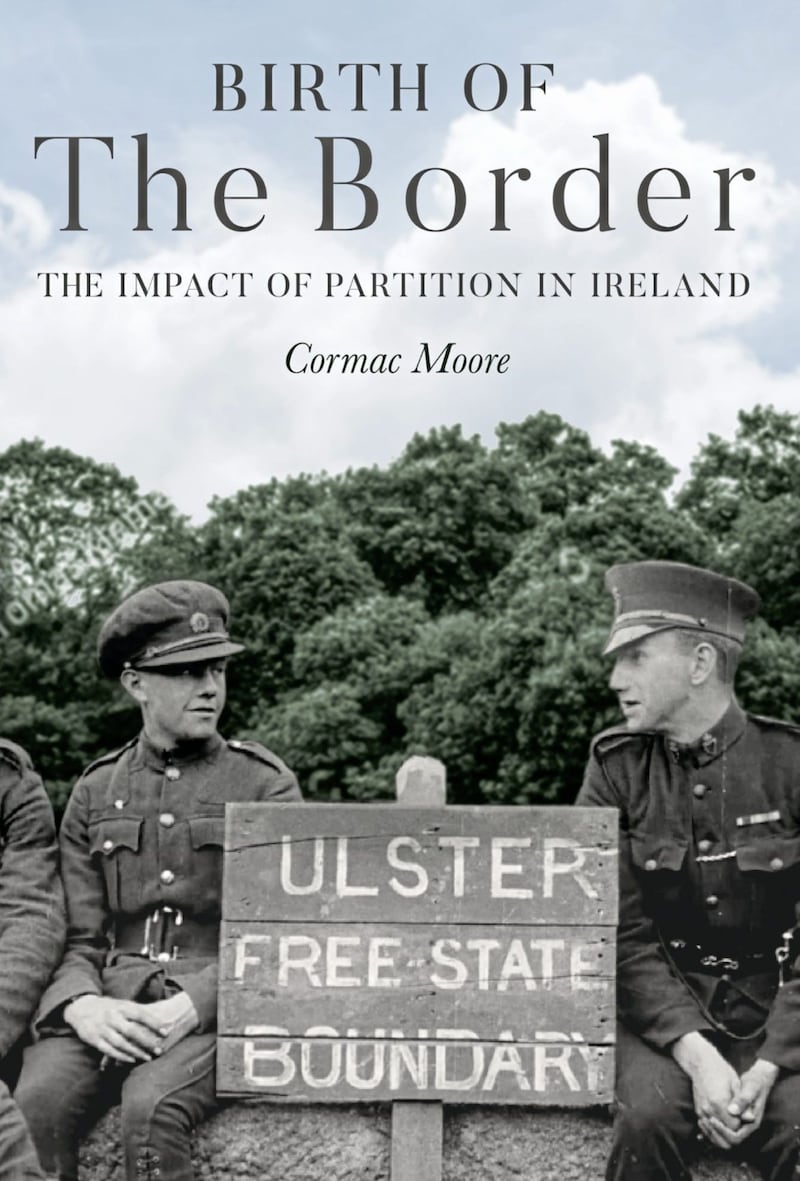

:: Cormac Moore is the author of Birth of the Border: The Impact of Partition in Ireland, published by Merrion Press.