ONE hundred years ago, on November 1 1920, enrolment began for a new auxiliary police force, the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC), for the six-county area that would make up the new jurisdiction of Northern Ireland.

Northern Ireland came into being six months later, in May 1921. The Specials were created due to the escalating violence occurring throughout Ireland, particularly in Ulster, in 1920.

Ulster unionists had genuine fears that the state of lawlessness they saw in the south and west of Ireland was infiltrating their northern citadel. They had little fate in the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), a mainly Catholic police force, to protect them from IRA incursions.

Loyalists believed that in Ulster, as was happening throughout Ireland, the RIC responded to attacks by abandoning small barracks, concentrating on protecting larger ones which were shut and bolted from dusk to dawn, allowing the IRA free rein each night.

The unionist-leaning newspaper the Impartial Reporter described the RIC as "a broken reed".

Thus, unionists looked to take responsibility for the enforcement of public order for the province. Although the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) had been inactive in Ireland between 1914 and 1919, its members still retained their weapons. As the unrest spread to Ulster, many started to organise into vigilante groups. One, ‘Fermanagh Vigilance’, was organised by Sir Basil Brooke, future prime minister of Northern Ireland, who "felt that the hotheads on the Ulstermen’s side might take the matter into their own hands, if not organised".

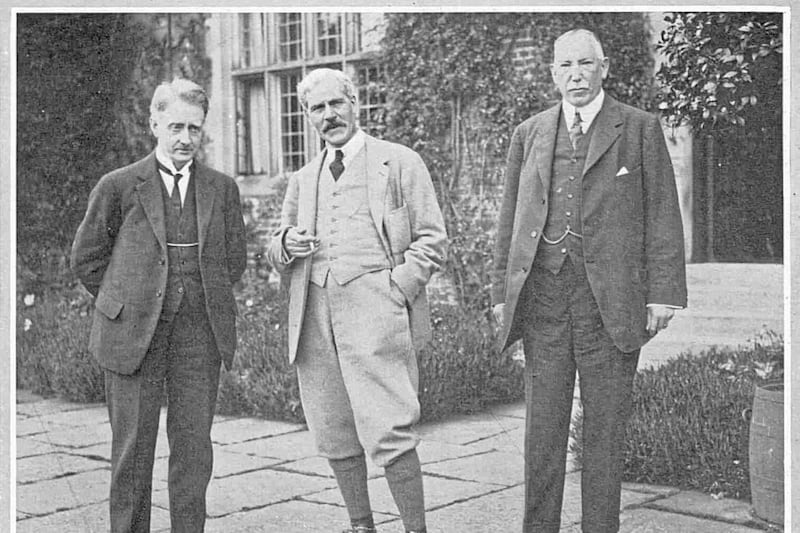

He urged Dublin Castle to form an official special constabulary in June, which was rejected. Instead he was offered caps and whistles to summon the RIC. Worried lest loyalists at the local level should pass beyond the Ulster Unionist Council (UUC)’s own control, Sir James Craig, who replaced Sir Edward Carson as leader of the UUC in February 1921, assigned Colonel WB Spender the task of resurrecting the UVF in order to harness loyalists’ "militant energies". The UVF was revived in the summer of 1920.

Although tacitly approved by the British government, the UVF still was an unofficial illegal force whose members received no pay nor indemnity if they were killed or injured. The unionist leadership sought official recognition of a loyalist police force from, and to be financed by, the British government.

Craig attended a ministerial conference in London on September 2 1920 where he used the pretext of looking to keep the extreme loyalist elements in harness, to demand an Ulster special constabulary. Craig was ultimately looking for the nucleus of the UVF to form an armed special constabulary for the six counties.

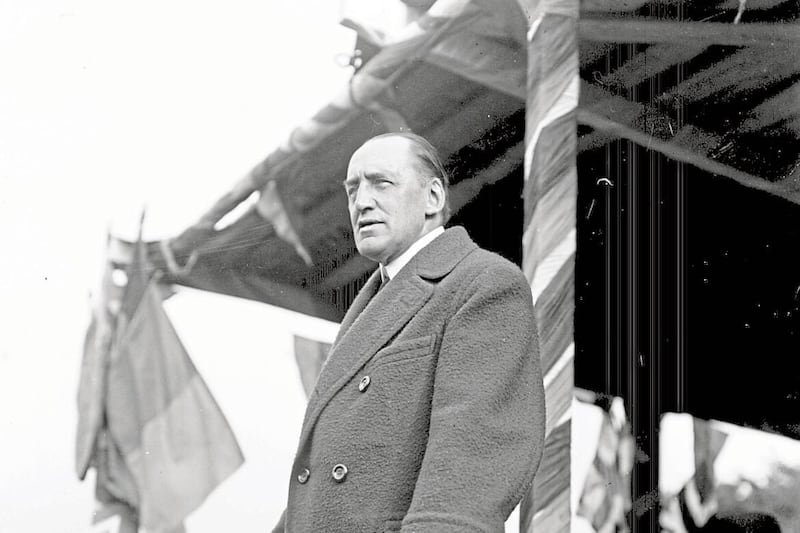

Secretary of State for War Winston Churchill had suggested that July of arming the "Protestants of the six counties" to maintain "law and order and policing".

The Conservative Party leader, Andrew Bonar Law was initially unsure and pointed out that, "if we armed Ulster, public opinions in this country would say the government was taking sides and ceasing to govern impartially".

The British military commander-in-chief in Ireland, Nevil Macready, and the leading civil servant in Dublin Castle, Under-Secretary John Anderson, were vehemently opposed. They believed it was a folly to recognise one of the parties in a faction fight and expect it to deal with disorder impartially, believing the decision would ultimately lead to a civil war.

However, with the British government prepared to ignore and even permit counter-killings and reprisals in Ireland this argument did not hold sway. The arming of loyalists would free up crown forces to crush the rebellion in the south and west of Ireland. Craig was granted his special constabulary.

The USC came into existence publicly on October 22 1920 with enrolment starting in Belfast on November 1. Although nominally under the command of the RIC Divisional Commissioner for Ulster Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Wickham, the USC had its own command structure with a full-time county commandant in charge of all Specials in each county.

Its members were organised into three classes. The ‘A’ class were full-time uniformed police auxiliaries, the ‘B’ class, which became the most notorious of the classes, were employed on a part-time basis and allowed to keep their weapons at home, whilst the ‘C’ class were only to be called out for emergencies such as invasions.

Officially Catholics were allowed to join the force; however, few did or were actively encouraged to do so. West Belfast Nationalist MP Joe Devlin declared: "If I had the power I would organise special constables to fight your special constables. The chief secretary is going to arm pogromists to murder the Catholics.

"The Protestants are to be armed, for we would not touch your special constabulary with a 40-foot pole. Their pogrom is to be made less difficult."

The USC was effectively a Protestant force from the very beginning. It did not augur well for the relations between the Catholic minority and the new regime.

It was unusual for the British government to grant a devolved region control over a paramilitary police force, strikingly so in 1920, as the entity of Northern Ireland had not even come into existence. The Government of Ireland Bill had not even been enacted at this stage. And, although Ulster unionists controlled the USC, the British government financed it with vast sums of money.

By the end of 1920, 1,417 men had enrolled in the ‘A’ Specials, 2,993 in the ‘B’ Specials and just 32 in the ‘C’ Specials. The USC subsequently mushroomed in size, reaching a membership of 35,000 by June 1922. Then, one in six of all Protestant males in the north were members.

The USC was effective in helping to diminish the IRA threat. RIC barracks reopened and there was a significant increase in raids for arms and wanted persons. Although the USC suffered heavy casualties at the hands of the IRA, many loyalists believed the overall casualties would have been considerably higher but for the USC.

Northern Sinn Féin and IRA members claimed in early 1922 that life under the Specials was ‘hell’. It is important to note that while an IRA threat existed in the north east from 1920 to 1922, given the vastly superior number of armed loyalists compared to armed nationalists it was nowhere near as apocalyptic as some unionists believed.

Many were caught up in anti-Bolshevik hysteria, fearing their homes and lands were under threat. As late as August 1924, Craig claimed to a journalist that he thought the Irish Free State would shortly break up, to be taken over by a Soviet republic established in Cork.

While one community felt more secure with the presence of the Specials, the other community felt the opposite. For the nationalist minority, the USC, particularly the ‘B’ Specials which was retained until 1970, was a notorious force whose members were the instigators of crimes against their community, including lootings and burnings of property, and reprisal killings of many Catholic civilians.

Harassed and humiliated by the Specials, the nationalist community felt the USC was a potent weapon deployed by the northern government, along with the draconian Civil Authorities (Special Powers) Act 1922, to subjugate Catholics under Protestant rule enforced by Protestant security forces.

Cormac Moore is author of Birth of the Border: The Impact of Partition in Ireland (Merrion Press).