WITH the passing of the Government of Ireland Act in December 1920, talk soon turned to who would become Northern Ireland’s first prime minister. Only two candidates stood out as options, Edward Carson and James Craig, the two towering figures in Ulster unionism’s opposition to Home Rule and the two men most responsible for the establishment of Northern Ireland.

Although Carson was officially asked to remain as Ulster Unionist leader, thus becoming the presumptive prime minister, it was always likely he would decline, which he did, claiming he was doing so because of his age and energy and that he would not be able to "work from morning till night, all day and every day", which was required of the new prime minster.

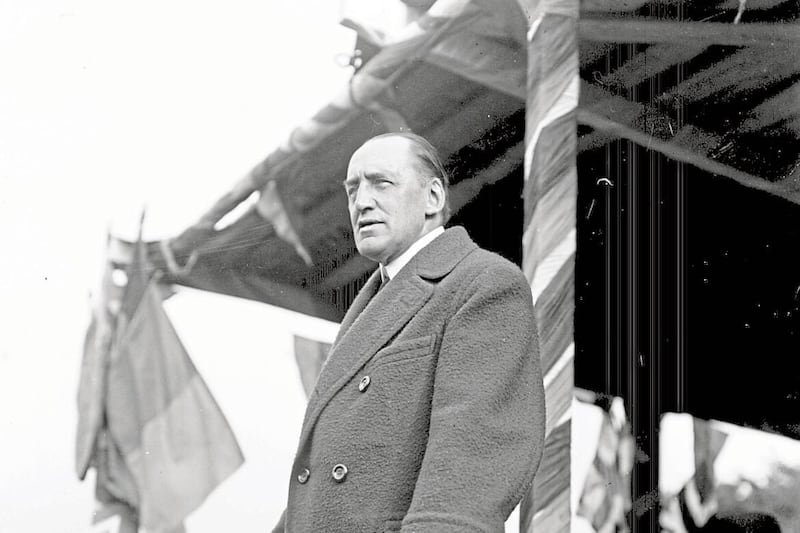

Carson’s resignation paved the way for the coronation of Craig as leader of the Ulster Unionist Council on 4 February 1921. While Carson presented the public face, it was Craig who masterminded the Ulster unionist campaign against the third Home Rule Bill.

Craig did not create the Ulster unionist movement nor did he bring ideas or ideology to it but his input on a practical level was immense. His greatest asset of organisation skills resulted in a disciplined and united Ulster unionist front that ultimately succeeded in the exclusion of most Ulster unionists from a Dublin parliament.

His pragmatic and administrative skills complemented Carson’s charisma and power of oratory, qualities he lacked. Craig’s biographer St John Ervine claimed, "effective apart, they were irresistible together".

Carson himself admitted: "It was James Craig who did most of the work, and I got most of the credit."

Craig, the Down-born unionist, also had none of the doubts surrounding partition that the Dublin-born Carson had. He had certainty of purpose.

After the First World War, Craig was in a unique position to influence British policy towards Ireland, serving in the British government from 1919 until 1921. In his last role as Financial Secretary to the Admiralty, he was in effect the First Lord, as the office holder, Walter Long, was too ill to carry out his duties.

Craig was the main Irish person consulted on the Government of Ireland Bill, which allowed him to influence it in the interests of Ulster unionism. He was instrumental in ensuring that Northern Ireland consisted of six instead of the nine counties of Ulster, even suggesting the establishment of a Boundary Commission to avoid a nine-county parliament.

The British government also agreed to Craig’s demands for a special reserve police force for loyalists, the Ulster Special Constabulary, and the appointment of an assistant under-secretary, Ernest Clark, just for the area that would make up Northern Ireland.

On becoming Ulster Unionist leader, Craig appeared to be mindful of governing for the nationalist minority as well as for the unionist majority of Northern Ireland. On the month he became leader, February 1921, he spoke of his "hope not only for a brilliant prospect for Ulster, but a brilliant future for Ireland". That same month he stated, "The rights of the minority must be sacred to the majority… it will only be by broad views, tolerant ideas and a real desire for liberty of conscience that we can make an ideal of the Parliament and the executive".

As 1921 progressed, Craig’s openness dissipated though, and he resorted to a combative position solely catering for Ulster unionist needs.

In his first extremely difficult years as prime minister, Craig was successful for Ulster unionists in securing Northern Ireland’s status intact, his slogan ‘Not an Inch’ being his steadfast position on the border. He overcame considerable threats from within and without to do so, utilising his relationships within the British government to prevent Northern Ireland from being answerable to a Dublin parliament instead of Westminster, and in the British government assisting, mainly through financing, the security apparatus that Northern Ireland deployed to combat threats.

It is true that the challenges facing Craig were daunting given the deeply divided society he governed over, but he never rose above his position as Ulster unionist leader. He used the powers of government to solely advance the interests of unionists.

His strengths of organisation and decisiveness, while effective during times of crisis, were lacking for most of the almost 20 years he served as prime minister. His short-sightedness prevented him from grasping the overall impact of his government’s decisions.

The government drifted with no long-term strategies to overcome many of the problems the north faced, presided over by stale old men who Craig failed to lead, who were allowed to run their departments without sanctions. Even with a stable guaranteed unionist majority, Craig was always frightful of electoral loss, making him afraid to enforce his views or agenda for fear of dividing unionism. He also had a habit of making decisions, both local and national, based on the opinions of the last person or group he met.

While Craig was more open-minded than other leading unionists, particularly the home affairs minister Richard Dawson Bates who saw all Catholics as traitors, Craig appointed him and allowed Dawson Bates to run such a crucial department that openly discriminated against Catholics without rebuke.

Craig permitted the admittedly difficult issue of dealing with the nationalist minority to fester. Instead of reaching out to Catholics through conciliation, he adopted a coercive approach that guaranteed a sustained reluctance by Catholics to recognise the legitimacy of Northern Ireland.

The policies of abolishing Proportional Representation (PR), the widescale gerrymandering of nationalist-controlled areas, the retention of the Specials, the prejudicial enforcement of the Special Powers Act which remained in place for decades, and the discrimination of Catholics in employment and housing, were all decisions that only catered for unionists and were bitterly opposed by all strands of Irish nationalism.

He hampered reconciliation and promoted discrimination through his insensitive comments, "I am an Orangeman first and a politician and Member of Parliament afterwards", and stating that Northern Ireland was "a Protestant Parliament and a Protestant State".

Overall in assessing Craig, historian Patrick Buckland’s words ring true that, "Despite an extraordinary career, James Craig remained a very ordinary man, mastered by and not master of circumstances and events".

:: Cormac Moore is author of Birth of the Border: The Impact of Partition in Ireland (Merrion Press).