LOCKDOWN has enforced a unique period of isolation and reflection for many of us, but for Moby, two decades from the height of his fame, that’s not too far from the norm.

The 55-year-old electronic musician has spent much of the pandemic doing what he’d usually do – spending time alone at his home in Los Angeles.

“Before the pandemic, I stayed home and I worked and went hiking and avoided socialising. So during the pandemic, I have stayed home and worked and been prevented from socialising,” he says.

“I feel this sense of guilt that my pandemic experience has been probably a lot more benign than most people’s… as someone who lives alone and works alone, I’m perhaps a bit too comfortable with my own company.”

This Benedictine lifestyle is a far cry from the hedonism of Moby’s early fame, chronicled in eye-watering detail in a new self-narrated documentary released next month.

Moby Doc charts the artist’s life from a traumatic childhood through to life as a teetotal animal rights activist. The in-between, though, is what’s most shocking: belying his thoughtful, even wonkish persona, Moby describes his battles with addiction and depression in astonishing detail.

In one of the film’s most stark moments, he even admits missing his mother’s funeral due to heavy drinking.

“I’ve appreciated other public figures who’ve attempted to be honest, or who’ve been willing to be honest,” he said.

“Not even public figures, but just humans, friends of mine, or people I meet at AA [Alcoholics Anonymous] meetings, who are actually willing to be vulnerable, willing to be honest, and willing to openly discuss the things that so many people are either ashamed of, or work so hard to hide.”

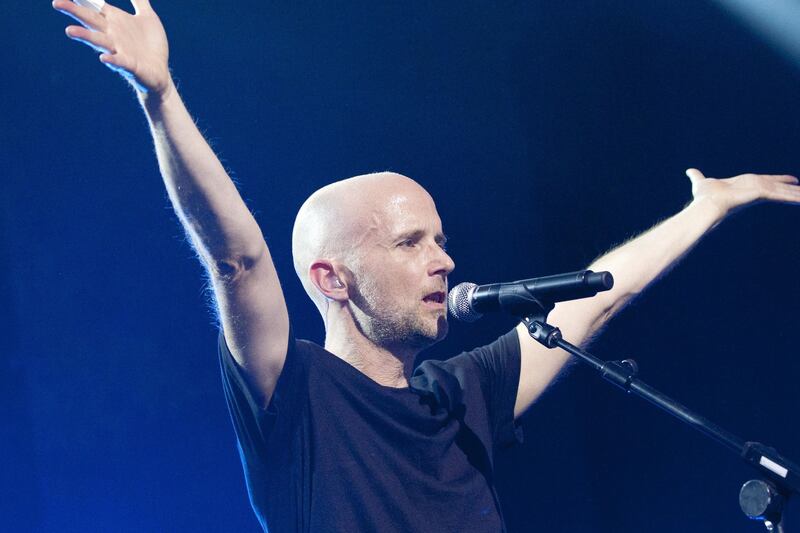

Moby became a household name at the turn of the millennium when his record Play and a string of accompanying hit singles propelled an outwardly awkward, shaven-headed bedroom musician to rock superstar status.

“To my shame, I kind of defined myself – and a lot of my wellbeing was largely the product of – being a professional musician, and being a public figure,” he admits.

“To that end, I went out and read so many articles written about me and I read reviews, et cetera.”

That might be fine when things are going well, but, as the Harlem-born artist explained, it makes it all the more tough when things go the other way.

“In around 2002, the tide turned,” he says. “All of a sudden the articles were negative, the reviews were bad. As someone who had largely propped up their sense of self and their wellbeing with the opinions of strangers, this was really challenging for me.”

More negative headlines followed in the wake of Moby’s recent memoir, Then It Fell Apart, in which he described dating actress Natalie Portman when she was 20. Portman denied this characterisation of the relationship, claiming she was 18 at the time and simply remembered a “much older man being creepy” with her.

Despite initially insisting his account was accurate, Moby later apologised for behaving “inconsiderately and disrespectfully”.

“It got a lot of attention, but it was, just in terms of page count, an incredibly minor… banal part of the book. But the world we live in is that’s what people prioritised,” he says of the incident two years on.

“Actual in-person relations are a lot more nuanced and probably not well represented by… the sort of quick 120-character media."

Another criticism, this time levelled at Moby’s music, relates to his use of the work of black artists in some of his most successful songs.

Play’s Natural Blues is effectively a remixed version of Trouble So Hard by African-American folk musician Vera Hall, while another well-known single from the album, Why Does My Heart Feel So Bad?, is built around vocals from little-known US gospel singers the Banks Brothers.

To some, including the artist himself, these reworkings were a mark of respect and helped bring them to new, much larger audiences. To others, they were simply exploitative.

“The only thing I’ve ever been able to say, in my defence… I don’t even like the word defence,” Moby starts when asked about this debate.

“When I have used African American or black vocals, samples, it’s out of a place of just profound love and appreciation for those voices, with the full understanding that I have no right whatsoever to use them or lay claim to any aspect of the experience that gives them their power,” he says.

He then recalls an anecdote from around the release of Play.

“I played some of the songs for [black comedian] Chris Rock. And I asked him: 'Have I done a bad thing?' I remember he looked at me, he said, ‘No’. He said beautiful music is beautiful music. And he said: 'You’ve made beautiful music.'

“And I felt like, OK, there’s an imprimatur that comes with that from Chris Rock. That really reassured me.

“But at the same time, whenever I have availed myself creatively of the black or African-American experience, there’s always guilt attached. And I hope that I’m not doing something disrespectful.”

“Cultural appropriation is a real thing,” he adds. “But we also live in an incredibly intertwined, complicated world. The clean lines between different types of artistic or spiritual and cultural expression. Oftentimes, sometimes they exist, and oftentimes, they’re quite blurred.”

Whether consciously or otherwise, Moby’s new record Reprise – an orchestral album largely comprised of reworked hits – includes the aforementioned songs with the famous vocal parts performed by black singers, namely Gregory Porter, Amythyst Kiah and Apollo Jane.

Making the record was also notable in other ways: for the first time in his career, the self-described “control freak” handed control over the arrangements over to someone else.

“The two or so years it took to make this record, I had a lot of challenging anxiety, having so many parts of the process out of my control. But then that wonderful sort of relief you get when you realise the people who are in control, are so good at what they do.”

He added: “I felt like as much as I love electronic music, it’s just, you know, you get a more unvarnished expression of the human condition, when it’s actually, when you’re just recording humans without electronics.”

One of the more poignant moments on the record is a tribute to David Bowie, a childhood hero whom he befriended and performed with after the pair became neighbours in New York.

The stripped-back rendition of Heroes references a special moment when he and Bowie performed the track on his sofa.

“It was just one of the most special moments of my life, not even professionally, but personally, spiritually, to sit with my favourite musician of all time and play a delicate version of my favourite song of all time.

“And so, in covering it for Reprise, I wanted to, I guess, both honour and sort of represent and pay homage to David, to my friendship with David and also to the sort of like the inherent vulnerable beauty of the song.”

:: Moby’s new album Reprise is released on May 28 on Deutsche Grammophon/Decca Records.