"I AM going to come back and see old Shannon's face again, and I am taking, as I go back to America, all of you with me." These were John F Kennedy's parting words to the Irish at Shannon Airport in June 1963, as the most powerful Irish American in history concluded his presidential visit to his ancestral homeland.

This trans-Atlantic love affair was cut tragically short when Kennedy was assassinated five months later. He would never "see old Shannon's face again", and though 24 Irish soldiers were rushed on to a plane to comprise the front-line honour guard at his funeral by special request of Jackie Kennedy, anyone from Ireland hoping to follow in the footsteps of the late president's Co Wexford and Co Limerick antecedents would soon find their American dreams stifled by new immigration rules he had helped shape.

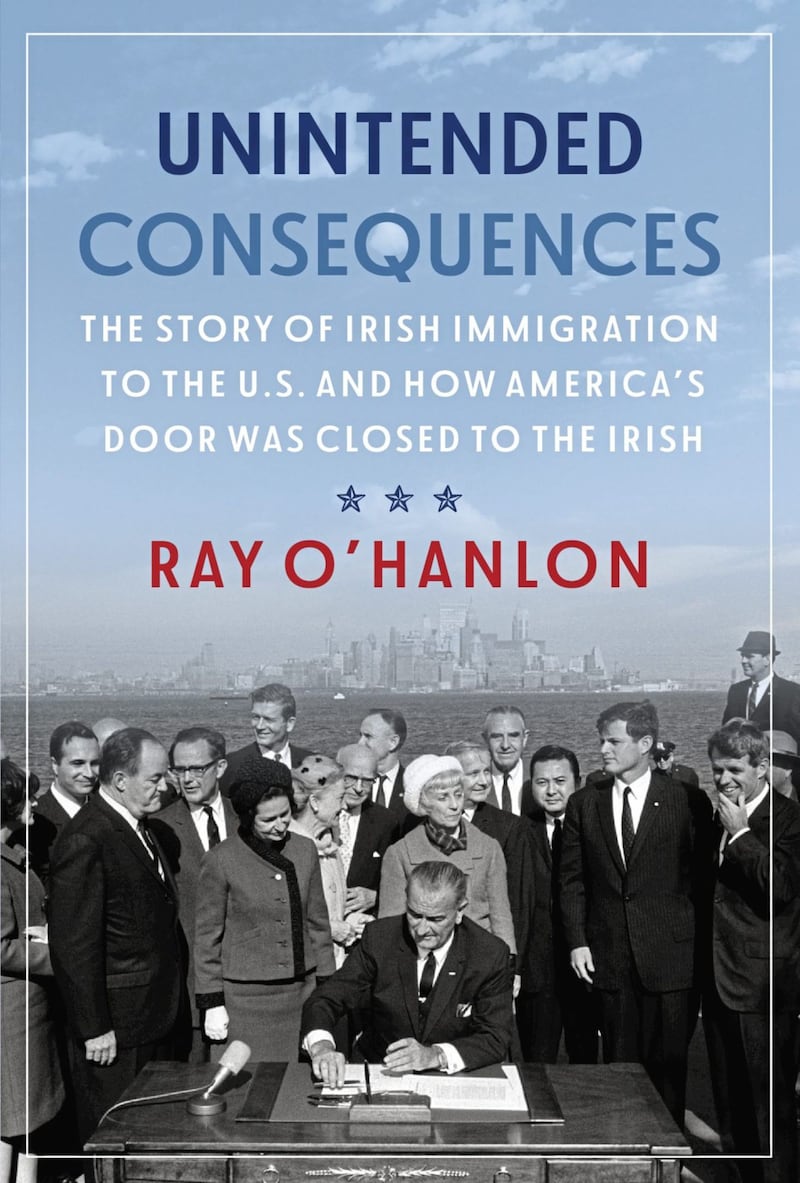

Signed into law in October 1965 by Lyndon B Johnson at a ceremony on New York's Ellis Island, the 1965 Immigration Reform and Nationality Act was a product of the civil rights era. JFK and his brother, Senator Ted Kennedy, had wanted to level the immigration playing field by abolishing America's 'national origins' based quota system which reflected the heritage of the US population by favouring Caucasian migrants from north-western European countries such as Ireland, Britain and Germany.

This system had made it relatively easy for thousands of Irish people to emigrate to the US every year. However, the 1965 Act ended this era of free movement across the Atlantic by placing a new ceiling on migration from the western hemisphere and throwing open America's borders to a broader base of immigration premised on family reunification with existing US citizens, workers with desirable skills and political refugees.

Within four years, the annual number of Irish visas granted to applicants had plummeted from several thousand to just a few hundred – and the 'unintended consequences' of Kennedy and co's good intentions are still being felt among the Irish American community today, which includes an estimated 50,000 'undocumented' Irish, the majority of whom arrived in the US via tourist visas and then simply never left: if caught, they face being deported and banned from returning to the nation they now consider home.

By his own admission, New York State-based journalist and author Ray O'Hanlon is "one of the lucky ones": the Dubliner got his US green card in 1987 when he married his Chicago-born wife Lisa, and has thus been able to live, work and raise his family without worrying about a visit from the Immigration and Naturalization Service – something which became an increasing concern for the undocumented Irish during the Trump administration's crackdown on all 'illegals'.

"I came at a time when so many Irish were coming to the States in the 1980s, but I didn't have to live in the shadows of being illegal and undocumented," he tells me.

Currently senior editor with the largest Irish American news weekly, the Irish Echo, O'Hanlon has spent much of his professional life reporting on the struggles of the undocumented Irish in his adopted home country, as well as those working on their behalf in Washington and elsewhere to undo the damage of 1965.

"I was working for the Irish Press in Dublin when I first wrote about this issue of the thousands of Irish people who were unable to get into the United States [legally]," he explains.

"That was something that surprised me and something that certainly surprised many Americans, who tended to think along the lines of 'surely the Irish of all people can get into America? Half the country is Irish!'

"I then very quickly got pulled into the story about campaigns for green cards and visas. There was a tendency at the time from Irish American leaders and other prominent people here to say 'look, don't make a fuss about this, we don't want to attract attention to all these young Irish – we can look after them, we can give them jobs and make sure they're OK'.

"But the numbers grew so great that this sort of sentiment was overwhelmed – and also, the young Irish who were arriving at the time were not inclined to be quiet."

O'Hanlon's new book Unintended Consequences: The story of Irish immigration to the US and how America's door was closed to the Irish, explores how Irish emigrants literally helped build the United States, fighting in its wars with such bravery that George Washington declared St Patrick's Day a national holiday, before suddenly being excluded by progressively minded legislation to the extent that today some commentators believe Irish America is now in danger of "dying out".

"It's really only this century that I started to hear more talk about the root cause of what we are dealing with now," explains the former Irish News columnist, who lives in Ossining in Westchester, just north of New York City.

"The 1965 Act was being mentioned more and more. I knew something about it, but the degree to which it actually played a role in the current situation was only just beginning to make itself plain."

Indeed, as O'Hanlon points out in the book, on that fateful day in 1965, LBJ actually remarked that "this bill that we will sign today is not a revolutionary bill – it does not affect the lives of millions".

"I believe the 1965 Act was absolutely in the spirit of its time," explains O'Hanlon, a father of "three New Yorkers", as he puts it.

"I think it was correct in its moral basis that America had to be diversified in terms of immigration and that people from other parts of the world, not just western Europe, deserved their chance.

"But then you have the unintended consequences, certainly for the Irish, which is what my book focuses on. There was no intention to exclude the Irish in '65 – in fact Teddy Kennedy offered to 'do a little deal on the side' for the Irish government, but they didn't want it: they preferred to keep people in Ireland in order to finally get the economy up and running."

Unintended Consequences acts as an effective prequel/sequel to O'Hanlon's previous non-fiction book, 1998's The New Irish Americans, which focused on the battles waged by the Irish Immigration Reform Movement and other pro-Irish American organisations in the era of President Reagan's 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act, which made it illegal for employers to hire undocumented workers as well as offering an amnesty for certain undocumented citizens – though sadly not the majority of 1980s Irish immigrants.

"The Irish Immigration Reform Movement created a huge furore and attracted a lot of media attention at the time," he tells me.

"The result of that was various efforts to deal with the situation: the Donnelly Visas, Morrison Visas, the Berman Visas, the Schumer Diversity Visas. In the end, over 70,000 Irish here did get a legal American life."

However, the fight for the Irish American liberty and opportunity continues.

"Serendipitously, the book is now coming out right in the middle of a renewed immigration debate on Capitol Hill," remarks O'Hanlon.

"And of course, we now have a president in Joe Biden who is more Irish than you or I, whom you would imagine would be sympathetic to an Irish point of view."

Indeed, the Irish American writer tells me that a copy of Unintended Consequences has recently "made its way to the White House", which begs the question: will President Biden miss his chance to finally unpick the 1965 Act and restore Irish access to the land of opportunity?

Say it ain't so, Joe.

:: Unintended Consequences is available now, published by Merrion Press. Order online at Irishacademicpress.ie/