IT is regularly stated that during the Anglo-Irish Treaty negotiations, which began 100 years ago in October 1921, Sinn Féin was primarily interested in issues related to sovereignty and the crown, and not on the issue of partition.

Given the amount of time and energy spent on Ulster before and during the negotiations, most of it instigated by Sinn Féin, this stance does not bear up under scrutiny.

It is important to note, though, that while Sinn Féin did care deeply about the essential unity of Ireland, it lacked a coherent policy on Ulster and was unable to press home its advantage on the British government's reluctance to break on Ulster.

In the talks between British prime minister David Lloyd George and Sinn Féin president Éamon de Valera that began immediately after the Truce of July 1921, de Valera rejected Lloyd George's offer of dominion rule for Southern Ireland primarily over Ulster, claiming that, "We cannot admit the right of the British government to mutilate our country, either in its own interest, or at the call of any section of our population".

During the Treaty negotiations from October 11 to December 6, the two primary issues discussed were Ulster and the crown. Even though Northern Ireland had been established under the Government of Ireland Act months earlier, the Irish plenipotentiaries were successful in re-opening the Ulster question, rekindling matters that unionists thought were settled.

On October 17 Arthur Griffith articulated the semblance of an offer on Ulster: "We are prepared to reason with them (Ulster unionists), and can probably come to an agreement with them if you (the British government) will stand aside. But, if they refuse our reasonable proposals, then people must be entitled to choose freely whether they will come with us or remain under the Northern Parliament."

In a memorandum the Irish delegation sent to the British negotiators on October 24, their policy on Ulster was further crystallised: "Should we fail to come to an agreement (with Ulster unionists), and we are confident we shall not fail, then freedom of choice must be given to electorates within the area."

With the Irish delegation stating that their allegiance to crown and empire was contingent on Ireland's "essential unity", Lloyd George and others within the British government pushed to change Northern Ireland's status if Sinn Féin would accept allegiance to the crown.

Lloyd George told Griffith and Collins that he "he could carry a six county parliament subordinate to a national Parliament". He was probably being disingenuous here as the Northern Ireland prime minister James Craig had emphatically rejected similar proposals in July.

Lloyd George also assured Griffith and Collins that he would resign "if Ulster proved unreasonable" rather than use force against Ireland. But, his cabinet secretary Tom Jones added the threatening caveat that the returning Conservative leader Andrew Bonar Law would then probably form a government and would introduce Crown Colony government for the south for a couple of months.

Lloyd George met Craig in early November and unsuccessfully tried to squeeze Craig into accepting an all-Ireland parliament. Craig did not budge.

He was aware of Lloyd George's cunning and duplicity and also of Northern Ireland's vulnerability. Even though Northern Ireland had been established in the summer of 1921, it was in a vulnerable position.

Powers had not been transferred to the new political entity. It had no control over policing, local government, education, in reality all powers needed for it to function as a viable government. Instead of Craig agreeing to compromise, he ended up winning concessions from Lloyd George, which calls into question Lloyd George's commitment to securing Irish unity.

On November 5, Lloyd George agreed to transfer government services to the north without the existence of a government in the south, with services scheduled to be transferred to the north from November 22 1921 to February 1 1922.

The Irish delegation were aware that the northern jurisdiction was not fully functioning when the conference began in October, services being withheld by the British demonstrated that partition could be negotiable, but they appeared unaware on how to use this to their advantage. The significance of services being transferred to the north seemed lost on almost all back in Dublin too.

With the avenue of reaching a settlement by pressurising Craig now closed, Lloyd George looked to squeeze the Sinn Féin delegation instead. Tom Jones dangled the idea of a boundary commission to Griffith and Collins.

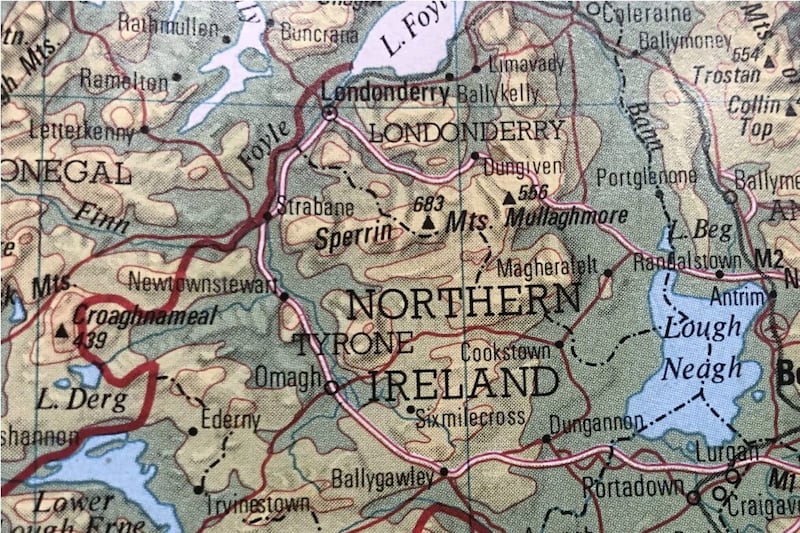

Collins was eventually convinced by Lloyd George on December 5 (just hours before the Treaty was signed) that the boundary commission would save "Tyrone and Fermanagh, parts of Derry, Armagh and Down" for the Free State. Griffith also believed that the boundary commission "would give us most of Tyrone, Fermanagh, and part of Armagh, Down, etc.".

He naively interpreted his assurances on the boundary commission as a ploy to help Lloyd George secure Irish unity. Instead, his assurances resulted in an animated Lloyd George using them against him as the negotiations reached their conclusion, leading to Griffith and the rest of the Irish delegation signing the Anglo-Irish Treaty on the morning of December 6.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty's main provision relating to Ulster was Article 12. It stipulated that if Northern Ireland opted not to join the Irish Free State, as was its right under the Treaty, a boundary commission would determine the border "in accordance with the wishes of the inhabitants, so far as may be compatible with economic and geographic conditions".

Central to the problem with the boundary commission was its ambiguity. No timetable was mentioned or method outlined to ascertain these wishes; how exactly economic and geographic conditions would relate to popular opinion, and which would prove most important.

No plebiscite was asked for, the clause was open to a number of different interpretations, and no time was specified for the convening of the commission.

The ambiguity suited Lloyd George perfectly. On the one hand, he could give the impression to Sinn Féin that large tracts of Northern Ireland would be transferred to the south, and on the other, to Craig, that it would just rationalise the cumbersome border, with perhaps the inclusion of Protestant strongholds to the north.

The Sinn Féin delegation clearly blundered greatly in acceding to such a vague and indefinable clause.

Nationalist leaders in the six and 26 counties were overly optimistic, as it would transpire, on the outcomes that would be achieved from this boundary commission, believing many areas in Northern Ireland would be transferred to the Irish Free State.

They were lulled into a false sense of security, believing they could continue to ignore the northern jurisdiction and its institutions. Their hopes would soon prove illusory.

Although the boundary commission provided for under the Treaty subsequently resulted in no change to the border, at the time of the signing of the Treaty, it was seen by most nationalists as a satisfactory method to end, or at least limit, partition.

And while Sinn Féin can justifiably be criticised for agreeing to such an ambiguous boundary commission clause and for not having a coherent strategy on Ulster, it is clear that Sinn Féin was responsible for making Ulster and partition a central component of the Treaty negotiations and that it cared deeply about the division of Ireland.

::Cormac Moore is author of Birth of the Border: The Impact of Partition in Ireland (Merrion Press, 2019).