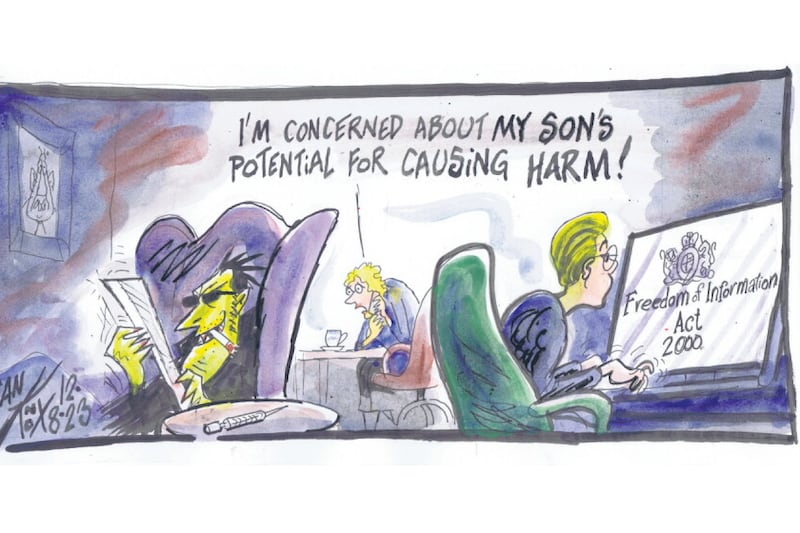

BRANDED a "sectarian disgrace" on Twitter by former DUP leader turned GB News presenter Arlene Foster and subsequently advised to "hang his head in shame" by vocal loyalist Jamie Bryson on the same social media platform, Irish News cartoonist Ian Knox caused a minor 'Twitter storm' with two of his famous satirical illustrations last month.

In one cartoon, a burly loyalist is comforted by his chums over his distress at being referred to as a 'Planter' by US congressman Richard Neal. In the other, elderly Orangemen parade with the aid of walkers and wheelchairs during the Northern Ireland centenary celebrations as an onlooker suggests that "next time around they'll need avatars" – a reference to the labour-saving holograms currently employed by septuagenarian Swedish pop sensations ABBA for their 'live' concerts.

Complaints lodged with the Independent Press Standards Organisation (Ipso) included allegations that the cartoon of the loyalists was offensive towards a minority group, an inaccurate stereotype and had raised tensions, while other complainants suggested the cartoon of the Orangemen was ableist and ageist.

However, Ipso found no grounds to investigate any of the complaints.

"Tim McGarry got in touch to tell me that he'd taken all of my cartoons down off his walls at home, just in case," chuckles Belfast-born Knox (79) of the recent controversy over his work.

"However, apparently he's now put them all up again."

Of the reaction from certain high-profile quarters, he adds: "I'm quite happy with it, quite honestly. I seem to have got through to Arlene to make her say the things she did."

As for Bryson, who has previously praised the cartoonist's work via his preferred platform of communication – that's Twitter, by the way, not a blue wheelie bin – it seems Knox is willing to give him another chance.

"I'm seriously thinking of removing Arlene from my fan club – but, if Jamie is up for it, he can stay," he advises.

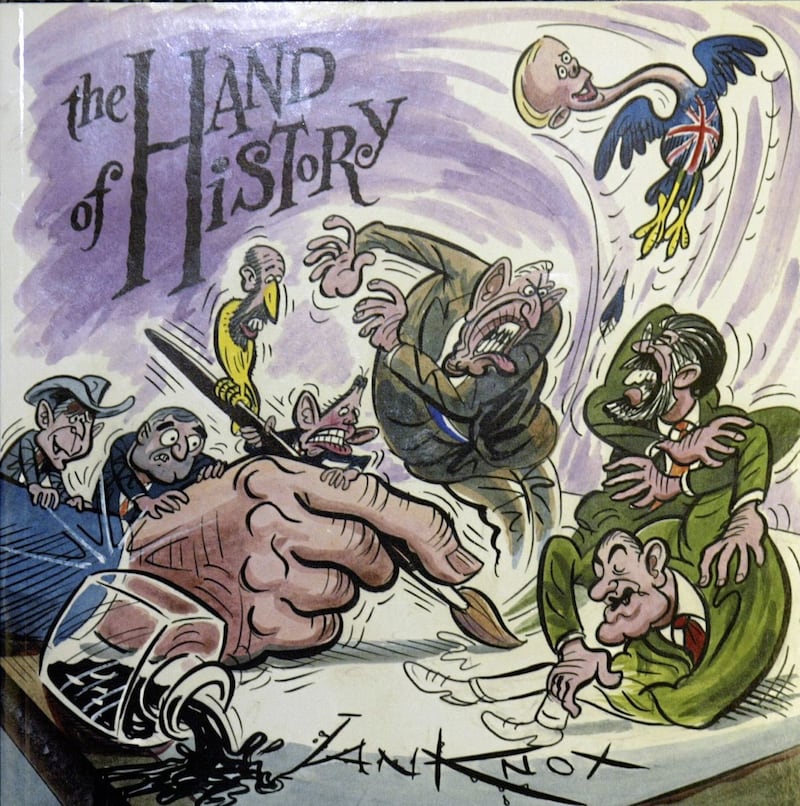

Based at his home-from-home in Ardglass since the onset of Covid, Knox continues to delight the majority of said 'fan club' with his regular satirical illustrations for the Irish News, where he has been resident cartoonist for over 30 years now.

Prior to joining the paper in 1989, the cartoonist cut his satirical teeth with the likes of Red Weekly and Socialist Challenge (earning him the professional nickname 'Blotski') and Fortnight, having previously helped entertain a younger audience through his work on IPC comics Krazy and Whizzer & Chips.

"One funny thing was that the vast majority of letters they got came from readers in Ireland," recalls Knox of early feedback from enthusiastic comic fans following the exploits of committed soap-dodger Pongo Snodgrass and other characters he was drawing at the time.

Flash forward to the present day, where the missives he receives for his Irish News cartoons can become rather less salutary.

However, Knox takes any flak in his stride. After all, a satirist can start to wonder if they're missing their marks when nobody gets annoyed on publication day – and things could be much worse, as he explains.

"You actually wish somebody would complain sometimes," he tells me of his four cartoons per week contributions to this paper, which were supplemented by regular work for BBC Northern Ireland's Hearts and Minds programme up until its cancellation in 2012.

"There was that Danish cartoonist [the late Kurt Westergaard, who died last year] who drew Muhammad and his turban with a fuse on it, like an old-fashioned bomb. He got death threats and had to go into hiding.

"I remember thinking, 'I draw hundreds of cartoons and nothing happens but that guy draws one and embassies go on fire and people riot around the globe'.

"But there you go – I'm quite happy not to have that. I mean, I'm privileged to be working in such, if you like, 'civilised' milieu as I am here."

Of course, having started work with The Irish News well before the peace process kicked into high gear, you might wonder just how 'civilised' a response he received from some of our paramilitary groups – organisations not exactly renowned for their sophisticated senses of humour – which featured in his work through the 1990s.

"It was actually when the violence stopped that the writs started coming in thick and fast," recalls Knox, who originally trained as an architect before finding his true calling with skewering sketches.

"There was far more trouble with politicians [than paramilitaries] regarding cartoons. I remember an editor saying to me that he had a drawer in which he put the writs and let them smoulder until they finally went out."

As recent events have underlined, it seems the unionists in Knox's fan club have long been his most effusive followers over the years, whether it's firing off writs about something in one his cartoons which has upset them, disparaging him on social media or occasionally just wanting to get hold of a print to proudly display in their WC.

The artist admits that the 'orange' side of politics here has always provided ample fodder for his work, as well as a healthy market in after-sales. For example, Knox has drawn many likenesses of the Paisleys over the years.

"Ian Senior never mentioned anything that I did, which was politically clever of him," he tells me of the late DUP founder and former First Minister.

"Occasionally, Ian Junior wouldn't like something that I did about him. But mostly with Ian Junior, he just wanted cartoons. That's the other side of it: unionists buy more of them – nationalists don't want my cartoons.

"Unionism is 'wild and wacky' in a way that nationalism isn't. Nationalism tends to be controlled and careful, whereas unionism is split by headbangers. I mean, it's just incredible.

"There's also guilt in unionism. They have to portray themselves as victims, just like in many other scenarios where the aggressor presents themselves as the victim.

"There used to be a television programme called Neighbours from Hell and there was one common thread that ran through it: the aggressor was normally the one who emoted when the cameras were rolling, whereas the victims were normally white-faced and pinched and spoke in a fairly understated way.

"I think that sort of applies to power blocs as well. The aggressor always goes in saying that they are 'defending' or putting things right and immediately the ['victim'] narrative starts. And now since we have social media, the whole thing has accelerated in a very depressing and unstoppable way."

One criticism levelled at Knox is that the cartoonist often resorts to unfair stereotypes when depicting Protestant/loyalist/unionist subjects and subject matter. It's a concern he takes seriously.

"There is a temptation to use stereotypes and, just as in literature, it's not good – it's a negative thing to use stereotypes," he tells me.

"A stereotype is basically a projection of prejudice and it's also very boring and, in a way, dishonest.

"I'm sometimes accused of overdoing 'simian loyalist' imagery – the drug dealing 'gorillas' and stuff like that – and I probably use too many Orangemen to portray unionists.

"It's hard, but people have to know who it is [I'm drawing]. Maybe if I could come up with a new way of portraying a unionist..."

In the wake of the recent criticism by Arlene, Jamie and others, Irish News columnist and former editor Tom Collins sprang to his cartoonist colleague's defence while simultaneously bemoaning how Knox's illustrations can immediately sum-up complex situations in a hugely impactful manner which text-based commentators can only dream of.

"Before human beings developed language, they made their judgments with their eyes," muses Knox.

"I think that the power of a cartoon comes from the fact that its message goes into a different part of the brain than the written stuff.

"If somebody is said to be hard up but you see them driving a Lamborghini, it's the Lamborghini that forms your judgment. So if I draw somebody a certain way, people pick up my message and believe it because they've seen it.

"So I'm aware that power exists – and I use it."

He adds of his subjects: "Nobody imagines that I'm doing an insightful study of their personality or anything like that – they are cyphers for what they say. And I infuse them with what I want. Somebody could be the worst in the world one day and the best in the world the next.

"I like to draw them as characters that they would imagine themselves to be very distant from. And people who take themselves seriously are the most fun to draw."

Thus, every time the cartoonist goes to work, he's basically revisiting, expanding and further populating 'Planet Knox' – a surreal yet recognisable cartoon version of our own world populated by caricatures of familiar figures. A nice place to visit, perhaps, but you probably wouldn't want to live there.

"Indeed – and if they look at it too long, people will have nightmares," he smiles.

Some people more than others, naturally.