A POEM that comes in a dream is "a marvel the awake mind has lost" argues poet Cherry Smyth who once dreamt she was taken to a deserted house by the IRA and tied to a chair, about to be shot.

"I can't die," she remonstrated with her imaginary captors. "I have more to write."

In many ways the Ballymoney-born poet and writer speaks for the 21 female authors - all of a 'certain age' - from across Ireland who have contributed to Look! It's a Woman Writer! which documents individually fraught, funny, desperate, inspiring and groundbreaking journeys towards the holy grail of publication.

In Belfast on Tuesday October 5, three of the contributors - Sophia Hillan and Ruth Carr from Belfast and Co Antrim-born author Máiríde Woods, from Dublin, will be guests at a special event and reading at the Irish Secretariat.

The aforementioned Smyth, now based in London and whose fourth collection Famished explores the Irish famine - "and how imperialism helped cause the largest refugee crisis of the 19th century" - was set to attend but is unable to make the date due to teaching commitments.

Éilís Ní Dhuibhne, editor of Look! and herself one of the contributors, traces her idea for this unique collection of essays back to the aftermath of the Waking the Feminists movement in 2015.

Created in protest against the poor representation of women playwrights in Dublin's Abbey Theatre's 'Waking the Nation' programme commemorating the centenary of the 1916 Easter Rising, Ni Dhuibhne points out that many of the complaints raised were the same she and her "sister writers" had been making since the 1970s and 1980s.

"Although we were fully supportive of Waking the Feminists and aware that in the Irish theatre world, in particular, gender equality has not been achieved, I felt that the earlier revolution regarding gender issues in Irish literature had already been largely forgotten," she says.

"Women have been creating literature for a very long time, in Ireland as elsewhere, but until the late 20th century they were in a minority.

"Now, in 2021, the fiction scene in Ireland seems to be dominated by women, but the scene in which these writers deservedly thrive was created by the previous generation; the female writers who emerged in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s into an Irish literary salon which was dominated by men to an extent which seems almost unbelievable today."

She did not ask her contributors to address the question, 'What has changed?' - "because we know the answer: a great deal" - but simply asked them to write about their own literary journeys.

In many cases, the results are as moving and page-turning as their best fiction. Northern Ireland writers, in particular, draw on themes of death and terror, of writing against the backdrop of the Troubles as well as dealing with the "macho" reality of a glass ceiling which, as award-winning Co Tyrone novelist Martina Devlin asserts in her snappy foreword, may now be cracking, but "could still use a few hard whacks".

Certainly, the prospect of a grim reaper waiting around the corner spurred on a number of authors, among them Sophia Hillan who paints a paradoxically beautiful and painful portrait of her battle with a rare cancer - a momentous life event which proved the unexpected catalyst to "get published" before she was 30.

An academic, teacher and author of books including The Cocktail Hour, The Way We Danced and The Friday Tree, she writes her account with honesty and humour, revealing how she found her way into fiction via a hospital bed at Dublin's Jervis Street Hospital, waking up one day to find she was lying under a name sign reading: 'Sylvia King: Fluid's only'.

"I can read upside down and back to front: Lewis Carroll taught me how," she quips.

"What use that is I no longer know: all I know is that my name is not Sylvia King but Sophia Hillan and that I did not put that apostrophe there."

The year was 1975 and she was 25 years old, about to be given the grim news that she had a rare neuroendocrine tumour - a cancer that would re-emerge 33 years later and lead to yet another flurry of "five-year plans" of writing targets.

Interestingly, Hillan, a former associate director of QUB's Institute of Irish Studies, does not see herself as a victim of cancer or even as a "person battling it"; rather, "It is just there. I am also here. We co-exist."

It is almost like holding a mirror up to herself; a portal into the Lewis Carroll-inspired "looking-glass" world of her childhood - "the not-world where the not-people who almost looked like us, but not, lived their parallel, mysterious lives".

But while the academic-turned novelist recalls a "glorious period" at Queen's University in the 1970s when Seamus Heaney was on the teaching staff, another then unknown Belfast student, Anne Devlin, came within punching distance of the Troubles.

Studying at the New University of Ulster (as it was then called), she was on a civil rights march from Belfast to Derry in 1969 when the march was attacked by loyalists.

Devlin was struck on the head, knocked unconscious, fell into a river and was brought to hospital suffering from concussion. The march was later echoed in her 1994 play, After Easter.

Reflecting on her activist days in the book, she says simply: "If I had stayed in politics in Belfast I would be dead. And I wouldn't be a writer. I took up writing plays because my dreams (nightmares) would not allow the events I had lived to pass into history. I used the plays to find my way back to live a whole self."

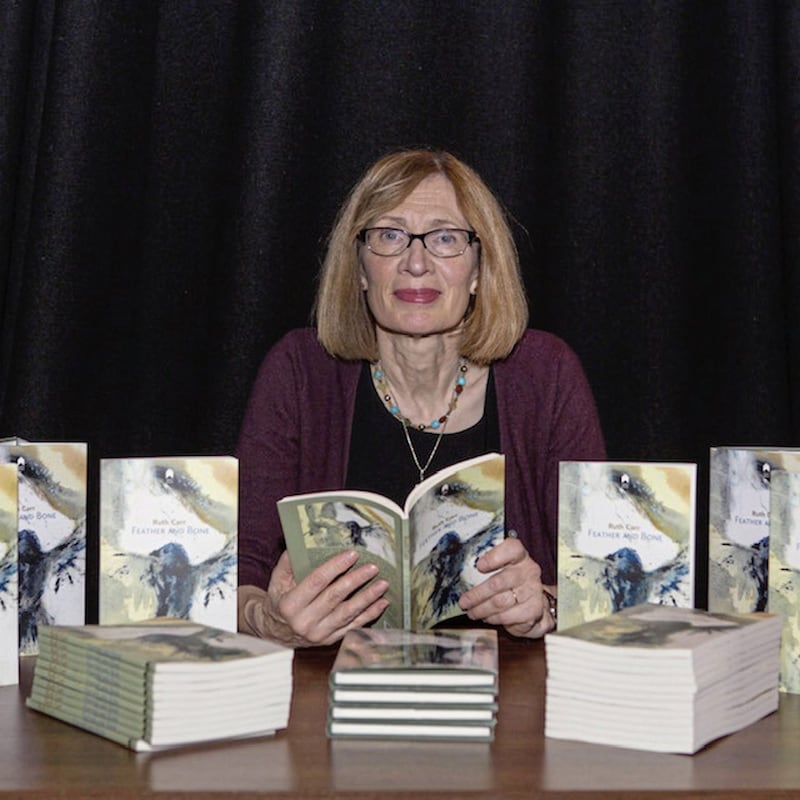

For contributor Ruth Carr, who edited the first collection of women's writings, The Female Line - published in 1985 by the Northern Ireland Women's Rights Movement - the Troubles meant that the first time she won a literary prize, the awards ceremony was cancelled.

"It was 1969 and due to the state of unrest, the awards ceremony at the New University of Ulster (as it was then called) was cancelled," she writes.

"I received a letter with a cheque in the post. I remember also that when the poem was later published in the school magazine, it was a sobering experience.

"The subject was my father and our struggle to communicate with one another. This difficulty was confirmed by the fact that he was very proud of my success but ignored what the poem was asking of us both."

Meanwhile, family tragedy is addressed by Hennessy Award winner Máiríde Woods who writes joyfully about gaining early inspiration from fantastical tales of leprechauns inhabiting the woods around Glencar, Co Antrim, but also opens up about agonising pain in later life.

"In the early 2000s my eldest daughter died suddenly," she recounts.

"My husband left. In the face of such happenings, getting published seemed irrelevant."

Yet she continued to write obsessively to "hold back the darkness", her current work still reflecting those losses.

"Today, I can see how my individual voice belongs to a generation and a place," Woods concludes.

"Perhaps I only have one story which I keep on telling in different guises. It never comes out quite as I intend. Our creations float beyond us, taking their chances on the waters of fortune."

Look! It's a Woman Writer! Irish Literary Feminisms 1970-2020 is published by Arlen House (arlenhouse.ie). Contributors include: Martina Devlin, Éilís Ní Dhuibhne, Cherry Smyth, Mary Morrissy, Lia Mills, Moya Cannon, Áine Ní Ghlinn, Catherine Dunne, Mary O'Donnell, Mary O'Malley, Ruth Carr, Evelyn Conlon, Anne Devlin, Ivy Bannister, Sophia Hillan, Medbh McGuckian, Mary Dorcey, Celia de Fréine, Máiríde Woods, Liz McManus, Mary Rose Callaghan, Phyl Herbert.