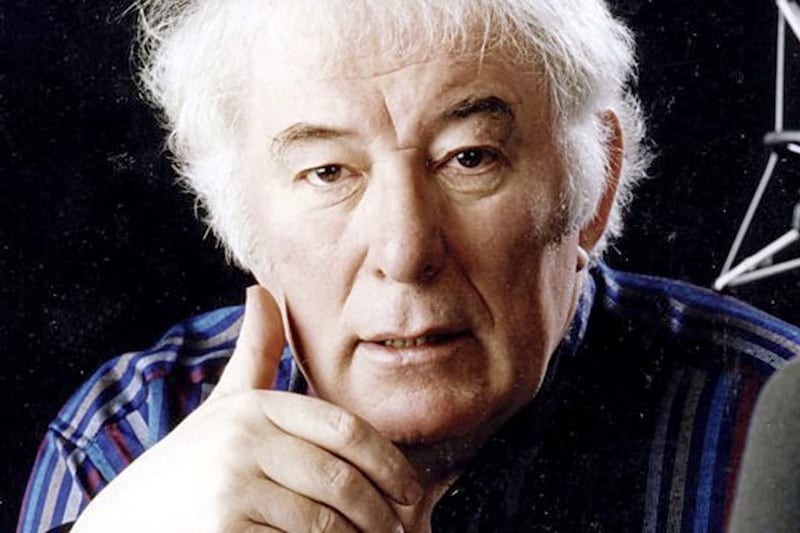

PULITZER Prize-winning Co Armagh poet and Princeton Professor Paul Muldoon looks younger than his 70 years.

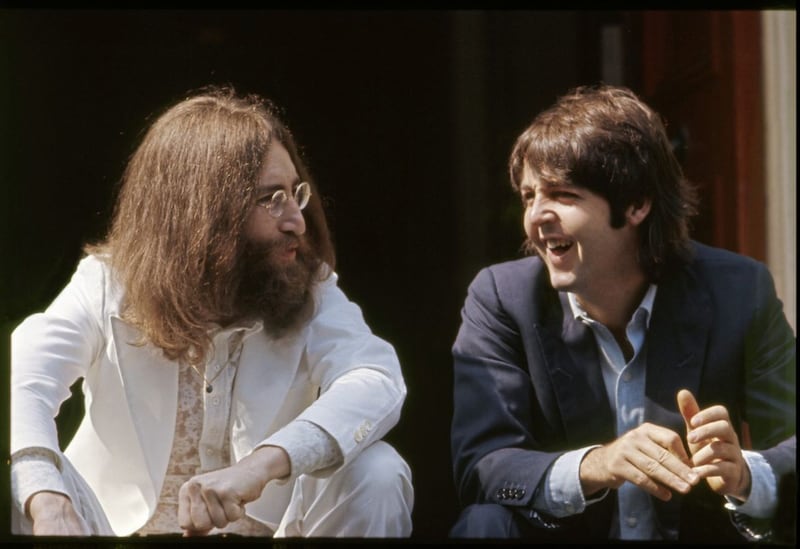

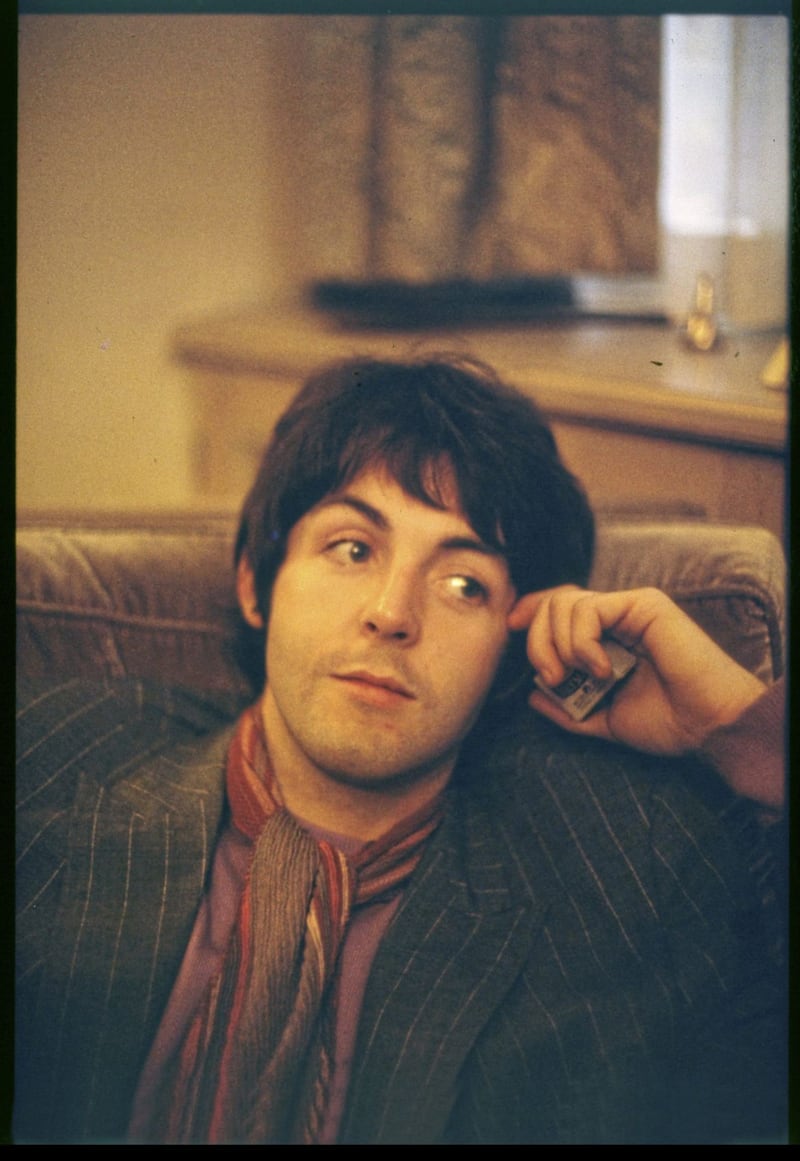

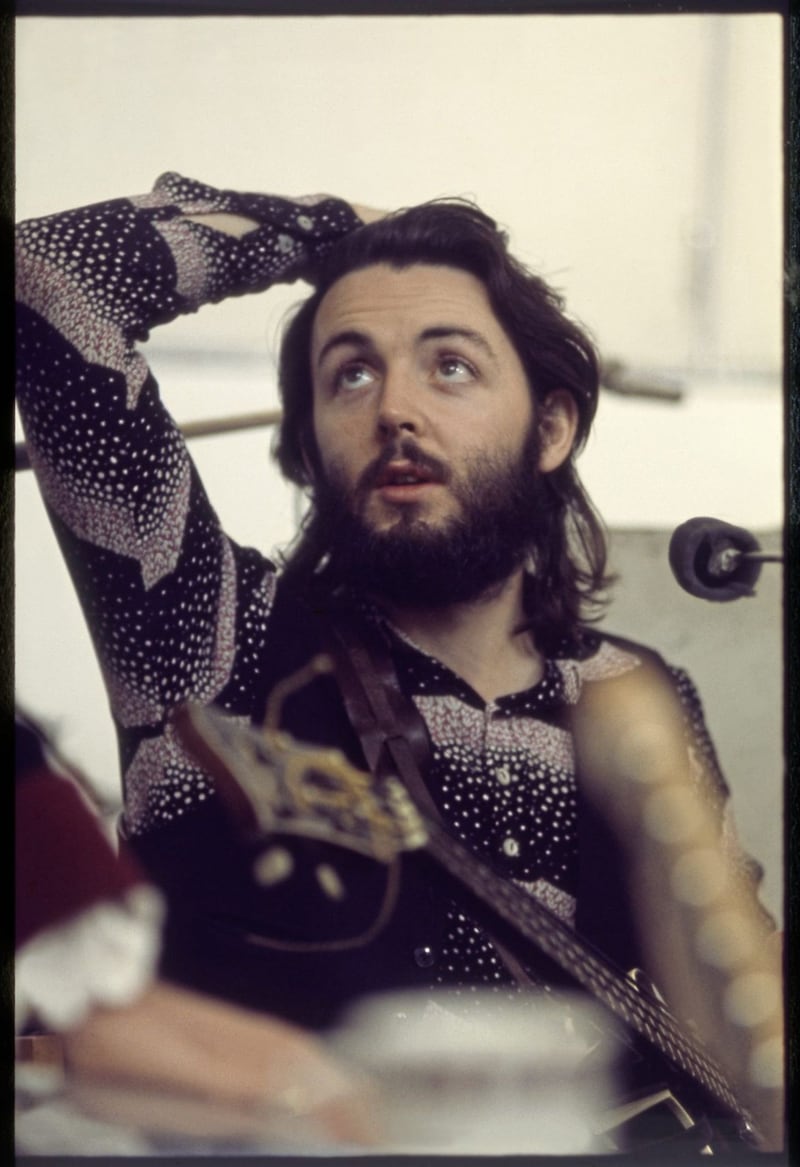

With only nine years between him and Paul McCartney, the pair enjoyed a valuable chemistry when collaborating on the abundant two-volume book collection of 154 songs The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present.

Muldoon suggests both were shaped by "all aspects of popular culture": "The shared UK culture of radio, television, film and music is what made us somewhat compatible, like many of a certain age we would remember all the popular songs of the late 1950s.

"We were on the same wavelength, in some way that made it easier but there's one complicating factor in that he's a Beatle... that gives it a whole other flavour."

For five years the "three-hour conversations" between the pair are "as close to an autobiography as we ever may come" he adds.

Muldoon, who worked as an arts producer for the BBC in Belfast for 13 years, offers a refreshing swerve away from the usual rock biography; instead, he discovers considered insights into the creative process while retaining a reverence for mystery.

"That's one of the great lessons we all may learn from Paul McCartney. It's not a particularly fashionable idea right now but if you scratch any interesting artist you'll hear that one of the key components to how they do it is that they don't really know what they're doing," he explains.

"It's not fashionable because people believe they know what they're doing and are in command. That's generally not that interesting; things get interesting when you open yourself to something you don't really understand.

"If you don't know what to expect, there's a chance the listener and reader will find themselves in a place they wouldn't expect to end up, that's where interesting art resides."

Muldoon, the son of a farmer and school teacher, grew up in Moy - on the Armagh side of the 'border' with Tyrone - says that Irish heritage was a notable aspect of their shared history. McCartney's Catholic mother and Protestant father both shared a rich Irish lineage.

"We were raised in similar ways", Muldoon confirms. "I don't think there was that much religion in his house but there was some Christian and more specifically Catholic iconography in some of the songs."

Perhaps the most obvious example remains Let It Be, which Muldoon suggests is about "resignation, that is also a very Catholic worldview; here we all are in this veil of tears, get used to it" before adding "of course Mother Mary has a Catholic feel, she is honoured in the Catholic tradition in a way she is not in the Protestant faith. Let It Be is also a translation of the word Amen which is used among Christian sects".

Muldoon adds that both he and McCartney "come from a particular tradition, we're both called Paul for the same reason - the feast of St Peter and St Paul on June 29. Quite frankly he is very conscious of his Irish roots, his family setting seems to be one that would be recognisable to many Irish people, it sounds like it was a party house or a cèilidh house with someone often playing the piano, having a drink or telling a story."

McCartney doesn't shy away from more controversial subjects. He was advised not to release his 1972 Irish No. 1 single with Wings, Give Ireland Back to the Irish, written in the aftermath of Bloody Sunday. "I think it was a perfectly legitimate position, says Muldoon, "the basic idea is not an unreasonable one."

McCartney indicates that Portstewart-born Wings guitarist Henry McCullough got into some trouble because of his Protestant background and admits the song was perceived by some as "a rallying cry for the IRA", adding "it certainly wasn't written to be one".

McCartney also clears up the long-held myth that he split the Beatles in April 1970 when discussing Dear Friend. He admitted to Muldoon that Lennon "quite gleefully" told the band it was over in September 1969.

"The portrait of John Lennon is a beautifully complex one", suggests Muldoon.

"It's one of love that comes through in the book and towards the end of John Lennon's life they were in a good place; they were communicating and hanging out to some extent. In this version of events, I see him as a schoolboy, I see them all as schoolboys in some aspects, they were kids and I can just see John Lennon saying, 'Guess what, I'm breaking up the Beatles, what about that?' There's a mischievous component towards it all, it's maybe even an almost whimsical decision to leave the band."

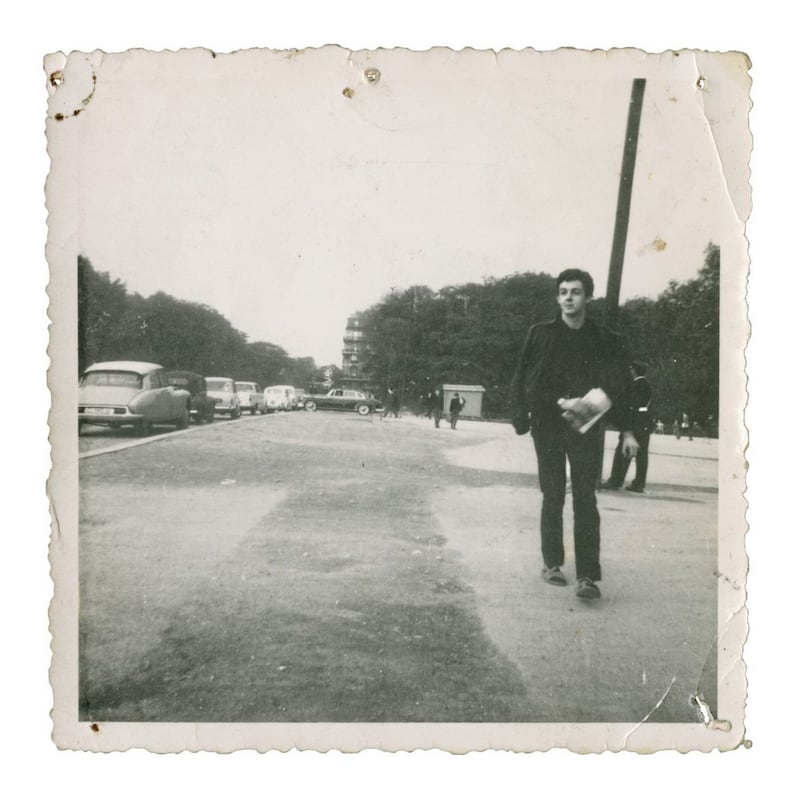

McCartney's relationship with English actress Jane Asher between 1963-68 also features when discussing the inspiration for a clutch of well-loved Beatles songs, among them And I Love Her and We Can Work It Out.

"The Asher house was very welcoming to him," explains Muldoon, who suggests her mother Margaret "was something of a stand-in for his own" late mother Mary who died when he was 14.

"As they say in Ireland, he had three hots and a cot. I think it kept him somewhat stable during that period (of Beatlemania), it was an anchoring structure that kept him tethered and half-sane from what I understand.

"She (Jane) was very well connected to the artistic milieu of London and it was partly through her he started meeting artists from other genres working in theatre and the visual arts."

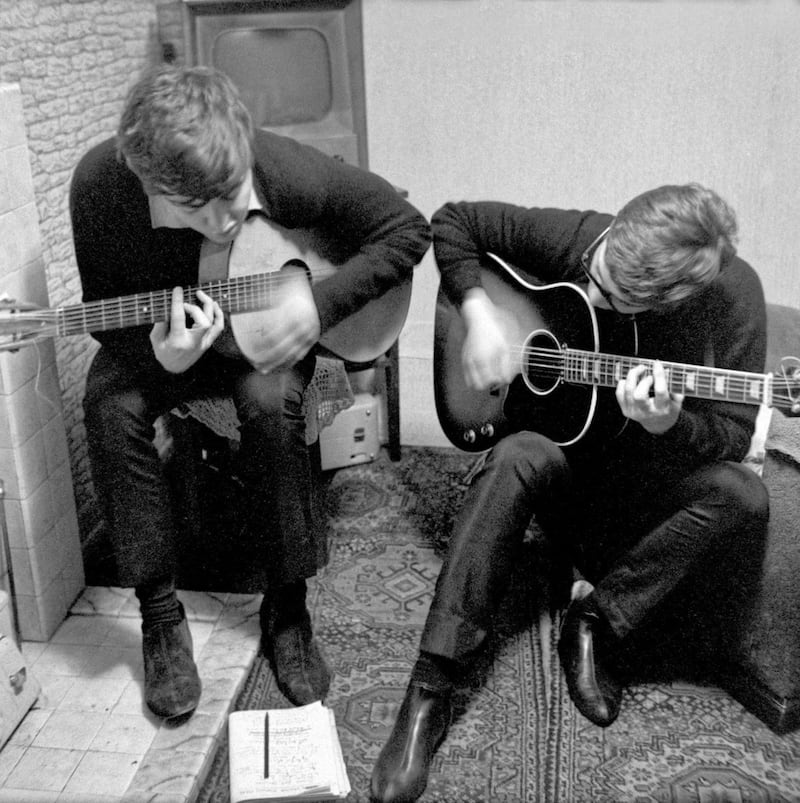

Muldoon adds that McCartney "draws upon, and extends, the long tradition of poetry in English" while pointing towards his "extremely good grammar school education".

A shared love of "wordplay" with Lennon is discussed during Ticket To Ride, the double meaning referencing McCartney's cousin Betty who ran a pub in Ryde on the Isle of Wight. McCartney summons captivating local memories of his early life and adolescence such as on Penny Lane which he describes as a "document".

Muldoon's enthusiasm for McCartney's ability to turn what might appear mundane into something poetic is one of the most absorbing aspects of the book.

"What comes to mind, is a line from Oscar Wilde - 'There were no fogs before Dickens, no sunsets before Turner.' To extend that idea there wasn't a Dublin before Joyce - these artists invent the place. In some sense, Van Morrison invented Belfast writing about Paris buns and Fitzroy Avenue and in a strange way The Beatles invented Liverpool... among other things."

The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present by Paul McCartney and edited by Paul Muldoon is published by Allen Lane.

Howdie-Skelp, Paul Muldoon's new poetry collection, is out now, published by Faber.