SEVERAL years ago the novelist David Lodge wrote the obituary of Park Honan, an author noted for his biographies, for the Guardian. Honan had written books on Jane Austen, Robert Browning, Matthew Arnold and Shakespeare.

Lodge said that Honan's book on Arnold showed his great strengths as a biographer: "Inexhaustible patience and a willingness to spend many years – to do anything, read everything and go anywhere – in order to build up a huge database of facts, often from previously undiscovered sources, that would then be distilled into a readable narrative by intense compositional effort."

Read more:

Anne Hailes: The brave stories behind reaching the summit of Mount Everest

Intense compositional effort sums up the work of many biographers, but it is only one aspect of the whole picture. The work involves laying out a detailed plan of where to start, how to gather material, the best way of carrying out research and interviews, reading around the subject, and deciding where to end it all before pulling it together into that readable style through multiple revisions and edits.

In March 2021, five months after her death at the age of 94, I was commissioned by a London publisher to write a biography of the writer and historian Jan Morris, a former foreign correspondent with The Times and Manchester Guardian.

She was the author of 58 books, 18 by James Morris, and 40 by Jan Morris following her gender transition in 1974. I had already written and edited two books about her and knew her personally for 30 years.

Her non-fiction work includes travel, history, memoir and autobiography, while a novel was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1985. Morris was vehemently opposed to a biography being written in her lifetime and turned down several requests from a number of writers.

Biography is a versatile form, there is no one-size fits all, and there are many ways in which the subject can be approached. For example, the work can be chronological, which considers a life from the basket to the casket, or it can be thematic. Others draw widely on letters, which provide a window into the writer's soul, as well as memoirs and diaries.

A biography must do justice to the whole life and tell the story truthfully, but may lend itself to speculation and surmise, although this was something I avoided. My main concern was to bring accuracy, balance, insight and proportion to the book, based on imaginative empathy.

Jan Morris's life offered a large canvas on which you could draw a map of the second half of the 20th century and pinpoint some of the defining moments which she covered as a journalist. She witnessed momentous events such as the rise of Egyptian nationalism in Cairo followed by the Suez Crisis, which almost led to a third world war.

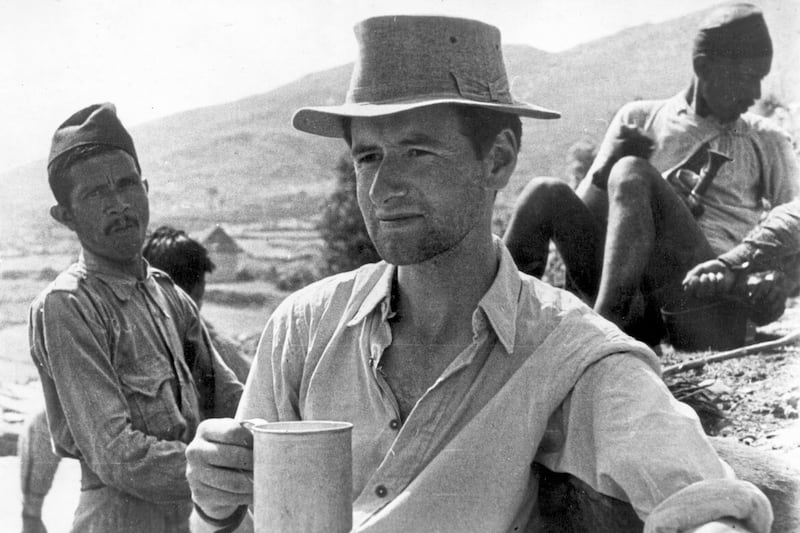

In 1953 Morris took part in the first ascent of Everest as a Times correspondent, covered the Adolf Eichmann trial, the collapse of Communism, the formation of new nation states in eastern Europe and the handover of Hong Kong to China. Morris also wrote a huge amount of political and cultural commentary on an array of subjects often focusing on her adopted Welshness.

It is little wonder that it took 600 pages to tell the story of her life and reflect on the times she lived through. In any biography there are sensitive issues involving the family. My book was not authorised, but her family and friends gave me considerable support in writing it, searching their memory to recall anecdotes and family history.

Read more:

Ex-journalist Paul Clements on his brain tumour op: I feel I dodged another bullet

Paul Clements goes Wandering Ireland's Wild Atlantic Way

Having written my two smaller books on Morris – one in 1998 during a fellowship at Oxford University and the other in 2006 – I had built the scaffolding of the narrative story of her life but still needed to visit archives in England and Wales.

During 2021 this presented a major challenge because of the pandemic with libraries, museums and archive centres only opening sporadically. When lockdown eased I spent time in the National Library of Wales in Aberystwyth where Morris's archive is kept and carried out 'fieldwork', visiting Shropshire to track her physical trail where she was educated during the Second World War.

In total, over a two-year period, I recorded more than 100 interviews by telephone or Zoom, or via letters and email. These oral testimonies of my informants were analysed and turned into crisp reported speech.

After the research and interviews, and when the facts were marshalled, the structure became clearer and the first draft was completed. However, the book was constantly reshaped with sections being moved around and rewritten as fresh material came to light.

Everything does not necessarily fall neatly into place. For example, parts of an interview with someone may end up being interspersed in different chapters, so writing it is a test of memory, trying to fit pieces together like a jigsaw puzzle. There is the need for a splash of magic too, as well as light and shade, with elements of humour and quirky stories.

Of course there is a case against biography. It is regarded by some as too prying or a form of busybodyism. The American writer Janet Malcolm was involved in a battle between Sylvia Plath's biographers and Ted Hughes.

Hughes had defended his and his children's privacy to control the publication of Plath's archive which led to much vilification from Malcolm who wrote: "Biography is the medium through which the remaining secrets of the famous dead are taken from them and dumped out in full view of the world. The biographer at work, indeed, is like a professional burglar, breaking into a house, rifling through certain drawers that he has good reason to think contain the jewellery and money, and triumphantly bearing his loot away."

A biographer must poke around, picking and searching with a jackdaw mind. Determination, perseverance and staying power are important qualities. The amount of time I spent in dark archives and on numerous other quests was daunting.

Henry James called reading the tangible printed documents with ink inscriptions "the visitable past". For me this meant looking through scores of buff coloured box files and notebooks, typescripts of Morris's books of travel and history, deciphering shaky or indistinct handwriting and tracing photographs from a wide variety of sources.

When I reached the final editing stage – after going through seven drafts including working with a sensitivity editor – I moved on to copy editing and then proofreading. I was looking for internal inconsistencies, timeline impossibilities, repetition or misplaced words, as well as harmonising, fine-tuning and sculpting the final text with a belt-and-braces check.

Another task involved compiling the index which in this case ran to 32 pages. This complex job demands patience, selectivity and intense concentration to ensure that the index and cross-referencing is an engaging road map for readers since effectively it represents a mini version of the book.

Telling life stories is a huge undertaking and is the dominant narrative mode of our times. Publishers believe it is a golden age for biography and history. Walk into a bookshop and the shelves are heaving with a vast array of titles covering these genres.

My aim was to avoid making the book too intrusive or prurient. I was driven by curiosity, but also by exploring the past and an all-consuming passion, bordering on obsession, to get as close as possible to understanding what was going on in Jan Morris's life, beneath the dazzle and behind the mask.

Some see biography as a 'blood sport', digging up the traumatic and shameful. Many other views have been expressed on the work of biographers. Germaine Greer once described life-writing as "a form of rape, a drive-by shooting". The writer Lesley Blanch called it "an assault by 1,000 pinpricks"; James Joyce said they were "biografiends", while Kipling called biographical writing "a form of higher cannibalism".

Most biographers do not sit in judgment to expose their subject in a dramatic way but present information with clarity to the calm eye of the reader. The best illuminate aspects of a life seeking to give glimpses of the subject.

Sometimes this is as far as the writer can get because people are complicated, inconsistent, contrary, and they change their minds. There are constant ups and downs in researching a life story, with disappointments and triumphs.

The work of others inspired me on dark days when little progress was being made. For his magisterial three-volume biography of the novelist Graham Greene, Norman Sherry, who died in 2016, spent almost a third of his life unravelling the web of obfuscation which Greene spun to prevent anyone "crawling all over my private life".

He took the footsteps principle to extremes, visiting numerous countries where Greene had spent time making up his characters and experienced many afflictions. In Mexico he fell ill with gangrene (as Greene had done) and part of his intestine was removed. In Panama he was met by gunfire in the streets, while in Liberia he chanced on a revolution, succumbed to tropical diabetes and his hearing was damaged when a gunman pushed a revolver in his ear.

After 16 years of travelling the world and two decades of writing, Sherry produced three volumes totalling 2,251 pages. Prior to Greene's book, he had worked on a biography of Joseph Conrad retracing the author's sea journeys, and wrote a telling comment: "I learnt with Conrad that wherever we go, whatever we do, we all leave tracks, and you can find them, even 80 years later."

This is one of the most valued views that I have read in my years of biographical research, and it motivated me to continue even when the task seemed overwhelming.

At times I felt that I was rowing out over a vast ocean of material and risked falling overboard. One trip to Wales was especially bleak. I had been carrying out research and interviewing a number of people and during my last recording I was exhausted and debilitated.

After returning home the next day I tested positive for Covid and was admitted to the Mater Hospital in Belfast as my oxygen saturation levels were low. Fortunately, I had a speedy recovery and was pulled through by the skills of a dedicated NHS team.

A nurse at the Mater whose cousins live in various parts of Wales asked me what I had been doing there as she frequently visited the country and was keen to read some of Morris’s work.

An excellent starting point, I suggested, would be her book on the cultural history of the country in which the author mingles topography, folklore, mythology and religion, and is called The Matter of Wales. I offered to write down the title for her but she replied, "I won’t forget, after all," she quipped, "you are in the Mater of Belfast."

Paul Clements’ acclaimed biography Jan Morris: Life from Both Sides is published by Scribe and is being launched in a paperback edition at the Island Arts Centre, Lisburn, on Thursday October 12 at 7.30pm. islandartscentre.com/event/jan-morris-a-life-from-both-sides-a-talk-by-paul-clements