IN an otherwise “quiet news” wet summer’s day in late July, it was reported that the Labour Party is reviewing its policy of not contesting elections in Northern Ireland.

In August, we heard of record levels of “business interest” in its conference in Liverpool next month and a surge in corporate sponsorship to an expected £500,000, up from £200,000 last year. Labour’s charm offensive with business appears to be generating some rewards.

While local politics and the regional economy may be entering (yet another) crucial period, events at Westminster will matter here too. Indeed they will matter a lot. The British economy seems to be in an era of “secular stagnation”, a concept revived by former US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers a few years ago, while the winds of political change may be blowing in the direction of a Labour, or Labour-led government.

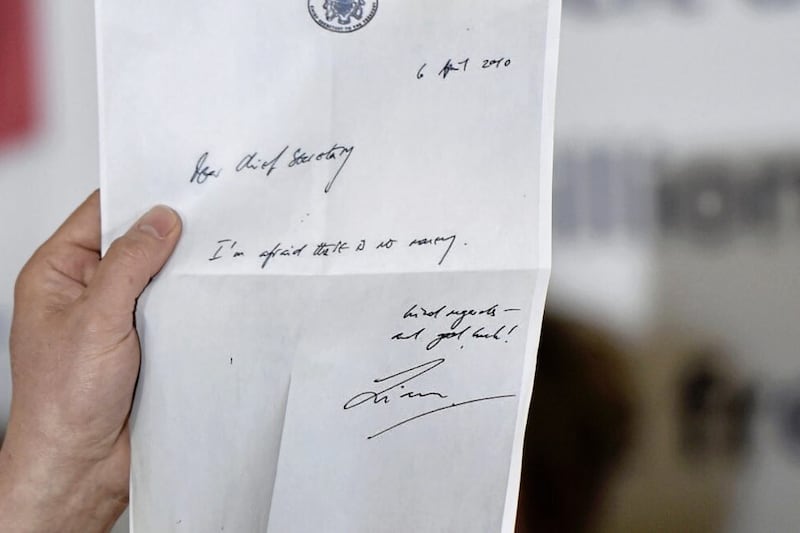

In 2010, Liam Byrne, then Chief Secretary to the Treasury under Gordon Brown, famously left a note for his successor … “I’m afraid there’s no money” – words that he has confessed are a matter of enduring regret, a gift to his political opponents.

Of course, a week is a long time in politics, and the outcome of the next general election is far from certain but the economic and financial inheritance for the new government will, almost certainly, be a sober one.

A measure of resilience

If we permit ourselves to be positive for a moment, the economy has demonstrated a greater resilience in 2023 than might have been expected. While monthly GDP readings are volatile, the economy continues, for now, to avoid recession. This relative resilience can be pinned on several props to growth from the supply-side (falls in energy prices, alleviation of product shortages) and the demand-side (tight labour market, strong growth in nominal wages and the depleting of household excess savings).

In addition, the full effect of monetary tightening is taking longer, reflecting the higher proportion of fixed rate mortgage lending (>80%) with a phased and extended re-set of borrowing costs over 2-3 years rather than an abrupt “shock” for everyone buying or paying for a home.

However, while a period of disinflation has commenced, the risks of “sticky” core inflation, a higher-for-longer interest rate regime, the freezing of income tax thresholds and general tightening of financial conditions and affordability are all likely to represent more formidable headwinds to consumer spending as we move into Autumn and Winter. Clearly, the risks of a (mild) pre-election recession are still real.

For a consumer-driven economy like Northern Ireland, the implications are obvious. While the dipping into savings pots has helped fund day-to-day expenditure and smoothed the impact on consumption, there will be limits to the savings-related boost to spending going forward. Those with deposits – typically older, middle and upper income households - already have a higher propensity to save.

A final policy re-set from Sunak?

PM Sunak has secured some credit for the thaw in relations with the EU, notably through the Windsor agreement, but overall, is struggling to achieve his five tests, at least on any reasonable timescale.

In July, PM Sunak offered the biggest pay rise in decades to public sector workers in England & Wales, something which is permanent and intended to be funded, in part, out of departmental efficiency savings. How difficult it will be to achieve this once out of a pre-existing budget let alone recurring. HM Treasury may recover about 40% of the increase in higher tax and national insurance revenues but this will be of no comfort to other departments. Pressure is now growing for a pre-election sugar boost of tax cuts, in part fuelled by better-than-forecast borrowing numbers year-to-date.

Would a Labour government be much different?

Put bluntly, future UK governments of whatever political colour will face major tax and public finance challenges from managing higher levels of debt to coping with the spending pressures of an aging society. We might hope that all parties are honest with the electorate about these.

Starmer will want to avoid a “Liz Truss moment” with markets at all costs while the tax burden is already at a post-war high. So far, Labour appears to have ruled out a new wealth tax, an increase in the top rate of income tax and a rise in capital gains tax. However, a hike on VAT on private school fees and abolishing non-domiciled tax status is planned.

It is possible he could make a bold splash be declaring reverse gear on Brexit but he appears to have made a political calculation that he still needs the votes of unrepentant Leave voters in England and it is too soon to reopen the debate with the referendum outcome less than a decade old. More likely perhaps, would be moves to forge a closer relationship with the EU, for example through an approach that favours regulatory alignment on goods for the UK as a whole, a potentially significant development for the resolution of local difficulties.

In truth, for all political parties, little can happen until the economy gets growing again and the execution of a strategic plan is urgently needed, one based on public investment and potentially, an unwinding of some of the Brexit changes aimed at boosting the labour supply and frictions on trade.

Until now, Starmer has seemed content to stay on the sidelines and let the Tories score “own-goals”. However, very soon he will be compelled to provide more detail on his vision and strategy. The party conference season is imminent. As for Sunak, he might get lucky … inflation falls faster than expected, the Bank of England cuts interest rates sooner and real living standards recover more quickly. Right now, who would bet on it?

Alan Bridle is UK economist at Bank of Ireland UK