LAST month, Irish Times journalist Cliff Taylor captured something of the essence of our times, at least from a financial perspective, of how changing living standards affect different generations in different ways. In a broad sense, the theme of intergenerational fairness has gained traction as issues of income and wealth inequalities, precarious employment, housing insecurity and the weaknesses in the social care system have moved up the agenda.

As the dust settles on the Autumn Statement, is the hard squeeze on living standards experienced in recent years over, or at least, coming to an end? The answer may be more nuanced than you think. We may all have been in the same storm, but paddling different boats.

On the face of it, the latest data is positive. Having peaked at over 11%, headline inflation fell sharply last month to below 5% and is course to ease further in 2024 while at nearly 8% year-on-year, regular pay in the UK is outstripping price growth by the greatest margin in 2 years. In Northern Ireland, median monthly pay has been growing at 6% y/y. Last week, Jeremy Hunt announced what are very likely to be material real terms increases in benefits, pensions and the national living wage while the 2 point cut in national insurance is estimated to put around £400 a year back into the pockets of average earners.

Falling inflation in parallel with strong nominal wage growth should take the hardness off some of the cost-of-living squeeze in 2024. The Asda Income Tracker has been indicating that the financial burden on households – the amount of cash left after taxes and paying for “essentials” - has already been easing during 2023 although the impacts on household groups are very uneven.

However, the underlying context remains sobering. The Resolution Foundation has calculated the typical UK household will still be £1,900 poorer by 2025 and Citizens Advice is highlighting record numbers of households seeking help heading into winter with the voluntary sector warning it will struggle to cope. Absent an unlikely repeat of last year’s additional government help for bills, households will be still be spending more on energy this winter than last.

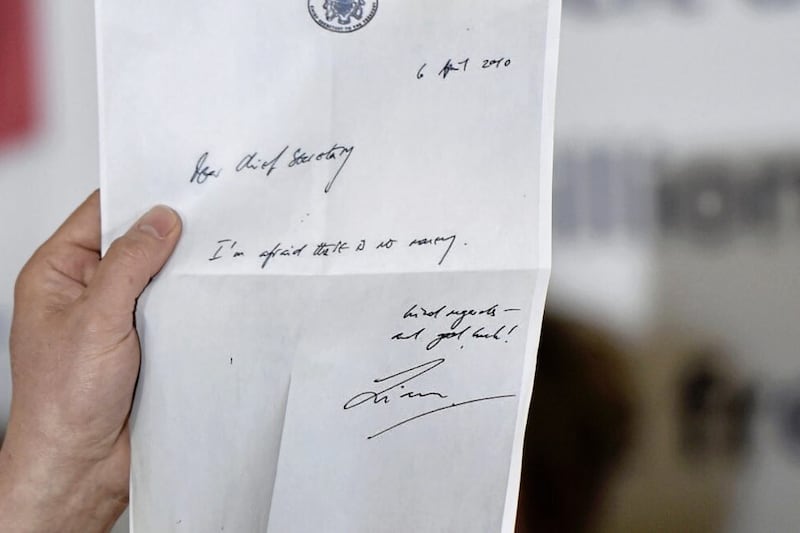

The biggest inflation shock in four decades followed by rapid monetary tightening has taken a heavy toll on incomes and as the UK and Ireland each move into pre-election periods, there may be political implications. Living standards do matter! Over 40 years ago, President Reagan put it bluntly when he declared the answer to “are you better off today than you were four years ago?” is often an important bit of context for voters. In the UK, the projected fall in real incomes between 2019-20 and 2024-25 will make this the worst parliament on record for growth and goes a long way to explain the latest opinion poll ratings and the prospects of political change.

In Ireland, the picture is slightly different. The economy has been growing but it would appear this is not translating to increased support for the incumbent government – not enough households it seems are “feeling it”, with polls indicating a dissatisfaction with issues such as access and cost of housing, health and other public policy areas. It was no surprise therefore to see the Dublin Government deliver a very substantial fiscal package last month that had an inordinate number of measures, a “catch-all” budget - everybody will be slightly better off, but nobody will be significantly better off.

The UK economy has been flipping between growth and contraction on an almost monthly basis and the latest OBR forecasts which underpinned the UK Autumn Statement confirmed the medium term outlook remains very dull, conditioned largely on assumptions that past increases in interest rates, coupled with supply-side constraints are expected to weigh on the domestic economy and against a backdrop of slower global growth and significant geopolitical uncertainties.

Any assessment of living standards must recognise that disposable incomes are not just a function of changes in real wages or pay but also reflect adjustments to benefits, taxes, employment and significantly, housing costs and interest rates. Rising rates in particular create winners and losers, partly reflecting age demographics and housing tenure. Broadly, those who own their homes outright (around one third of the population and likely to be at least aged 55+) and potentially with some financial assets (savings & investments) will invariably be in much healthier financial shape.

The Resolution Foundation recently estimated that total interest on bank accounts, cash ISAs and other savings will reach £90 billion in 2024-25 – or over £3,000 per household – up from just £5 billion in 2021-22. The long famine for savers is over, at least for the foreseeable future and for some more than others . . . the 10% of households with the most savings wealth will account for 65% (or £60 billion) of savings interest in 2024-25, receiving an average of £20,000 each, before tax. The 50% of households with the lowest savings will receive only 2 per cent of total interest income, or around £100 each, on average. Households aged 65-74 will gain 6x as much on average as those under 35.

In contrast, sharply rising borrowing costs and rental payments are significant headwinds, potentially impacting around two thirds of households to some degree. For just under 50% of mortgagors, the pain of the rise in loan costs is still to come, with the BoE estimating a further 4m fixed rate mortgages will mature and re-set to higher rates by end of 2026.

The affordability stretch for first time buyers seems particularly acute with the Regulator recently flagging a three-fold increase in the number of buyers taking out 35-year “ultra-long” mortgages, accounting for c 12% of all new loans now compared to 4% in 2021.

For those not yet on the housing ladder or in the rental sector for reasons of affordability, the current gradual deflation in house prices alongside growing signals that interest rates have peaked should be of some solace.

So is the cost-of-living crisis over?

For some “yes”, but clearly for many others there is still a way to go. For the good of the economy overall, perhaps the third who own their homes outright, especially those who have financial assets including good pensions and possibly are still in secure employment, the message is “keep spending” (responsibly of course and preferably on locally produced goods & services). For many in the other “two-thirds”, the cost-of-living crisis is enduring. Sound advice on financial wellbeing and budgeting is encouraged.

Looking ahead, a change in government at Westminster will inherit a very tight public spending envelope and this may prompt a greater focus on policies of income and wealth redistribution, primarily through the taxation system. Might we also see additional incentives to accelerate intergenerational transfers?

:: Alan Bridle is UK economist at Bank of Ireland UK