“THE way I would put it is that I made 18 new friends,” explains artist Colin Davidson of Silent Testimony, his 2015 portrait collection depicting a diverse group of people affected by the Troubles, which opened at the National Portrait Gallery in London earlier this week.

“I became really close to many of [the subjects] and still am close to many of them to this day: there’s a community of us that will travel depending on where the show is – I remember that myself and a delegation of the sitters went out to New York when it was on at the UN in 2018.”

While he’s best known for his striking large scale portraits of celebrities and public figures – famous sitters for the Co Down-based artist include Ed Sheeran, Seamus Heaney, Brad Pitt, Liam Neeson, Martin McGuinness and Queen Elizabeth II – Silent Testimony’s renderings of ordinary people whose lives were blighted by Troubles-related violence might be Davidson’s most important work.

Having set out in 2014 to try and highlight the losses experienced by a small sample of those ‘left behind’ by a peace process seemingly hyper-focused on accommodating the perpetrators of Troubles violence rather than providing closure and support for victims, survivors and their families, Davidson (56) found himself becoming hugely affected by those who agreed to sit for him.

“It was life-changing,” he admits of the creative process behind Silent Testimony, which was facilitated by the Troubles victim support group WAVE (Davidson is now a patron) and includes a brief text accompaniment alongside each painting outlining its subject’s story.

Read more:

- Belfast artist Colin Davidson to display artwork at Stormont for Good Friday Agreement anniversaryOpens in new window

- Retrospective a chance to look back in wonder at the art of Colin DavidsonOpens in new window

- Painter Colin Davidson says he will ‘forever hold dear’ sitting with the QueenOpens in new window

“You can’t walk into somebody’s home and have them take you into their daughter’s bedroom as it was left the morning that she left for the last time, and not be changed.”

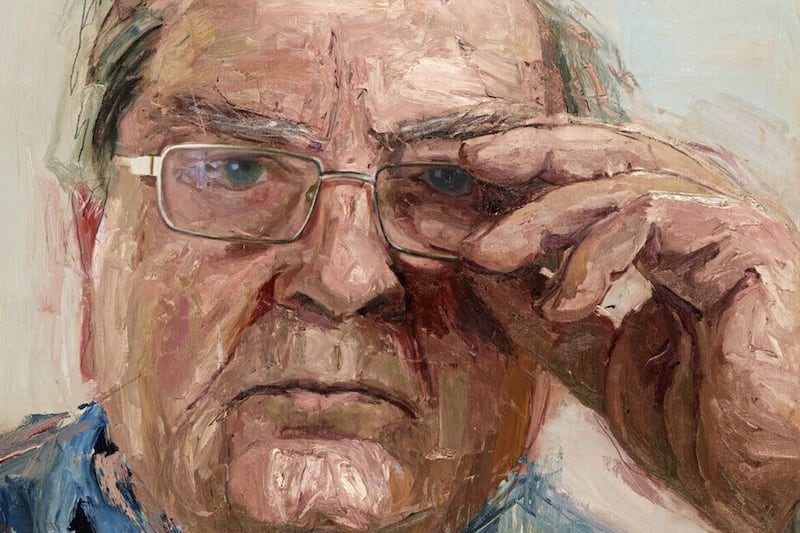

The Bangor-based artist is referring here to his portrait of Paul Reilly, father of 20-year-old Joanne Reilly. Joanne was killed when a car bomb exploded beside her place of work in Warrenpoint in April 1989: Mr Reilly sat for his portrait in Joanne’s old bedroom, which had become a shrine to his late daughter – the wall clock set permanently to 9.58am, the time of her death.

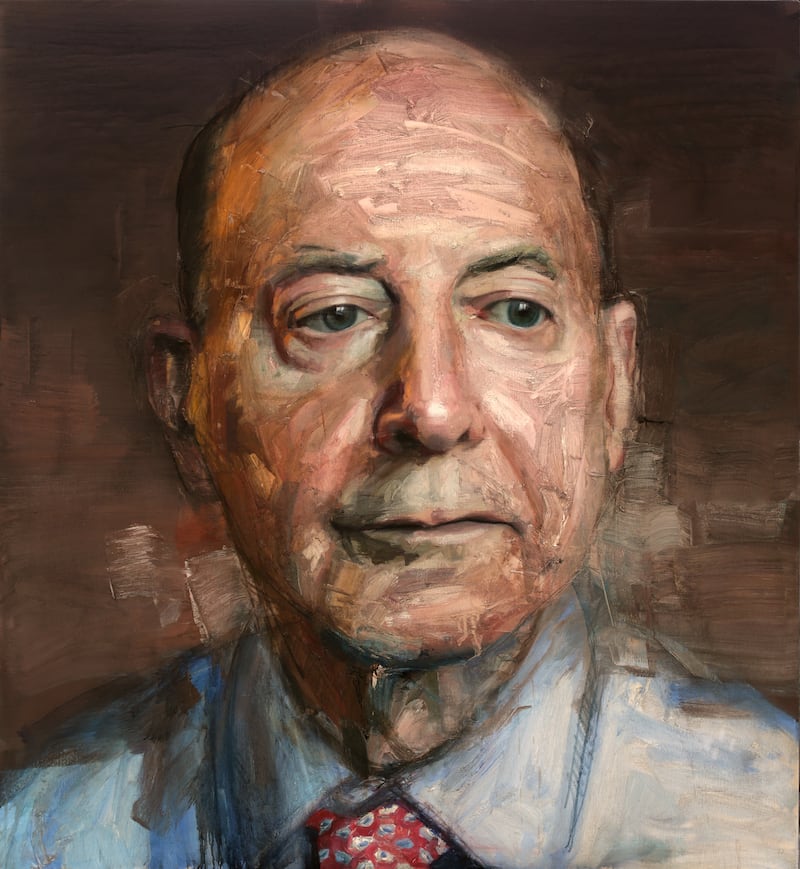

“Thomas O’Brien was inconsolable when talking to me about his brother’s death 40 years before,” he recalls of his sittings with the man who lost his brother, John (23), sister-in-law, Anna (22), and two nieces, Jacqueline (17 months) and Anne Marie (5 months) in the Dublin bombings on May 17 1974.

“It was totally unresolved grief.”

Sadly, some of the subjects of Silent Testimony are no longer with us: Thomas O’Brien, Flo O’Riordan and Walter Simons have all passed away over the past nine years, while Maureen Reid, whose husband James was killed in a Belfast pub bombing in 1976, died in March 2015 before the exhibition even made its debut at the Ulster Museum.

“Thomas, Flo, Maureen and Walter really hadn’t had an opportunity to tell their stories,” explains Davidson.

“So, for me to have been part of exposing potentially millions of people to their stories is a privilege. It’s an honour, and if they were here today, I trust that that would be a source of comfort to them.”

Of course, Silent Testimony’s themes of unresolved human trauma also apply to other victims of conflicts around the world, past and present, and the collection has toured internationally during the past decade.

“For me, while [the show] is specifically portraying 18 people, it also refers to the many tens of thousands who are just like them,” says the artist.

“I would hope that people understand that it’s as much a comment about us as a society right now as it is about those 18 individuals.”

Looking back at this poignant project, Davidson reflects on how it has helped reinforce his belief in the power of portraiture to provoke a visceral reaction in the viewer.

“I think what making this work has taught me is that I’ve really only been scratching the surface of what portraiture can do,” he tells me.

“We learn to read a human face, we learn to intimately read expressions, whenever we’re very, very young. And the nuances of that can be read in a portrait painting as well. Where a photograph is a split-second in time, a portrait can represent a lifetime.

“It’s an honour and a privilege to be afforded trust by people to attempt to expose something through their face that tells a deeper story.”

The Co Down man is rightly proud of Silent Testimony’s continuing contribution to an ongoing conversation about the necessity to provide support and closure for victims of violence in post-conflict societies – and specifically here in the north.

“There is a deep psychological aspect to making a portrait to start off with,” comments Davidson.

“But when I was making these portraits of 18 people who were still suffering trauma on a daily basis through loss that they experienced during the dark days here – that drove home to me, not only how worthwhile the project was, but actually what the true start and beginning of healing might be in this part of the world.

“That is, acknowledging what we did to each other here, acknowledging the human cost – and taking responsibility for it.”

Given recent developments like the Troubles Permanent Disablement Payment Scheme, which many victims of violence have struggled to access, and Westminster’s Northern Ireland Troubles (Legacy and Reconciliation) Act, which seeks to draw a line under the past by preventing the possibility of further investigations into Troubles-related crimes, the themes of Silent Testimony are perhaps even more relevant now than they were in 2015.

“The past is the past and there’s nothing we can do about it,” comments Davidson.

“But for people who are suffering loss, the past is their present. With Silent Testimony, I wasn’t really interested in the past – I was interested in now.

“It’s actually an exhibition about asking questions of where we are right now.”