THE British government’s ‘broadcasting ban’ targeting Sinn Féin and other paramilitary-affiliated organisations was one of the more bizarre episodes of the Troubles.

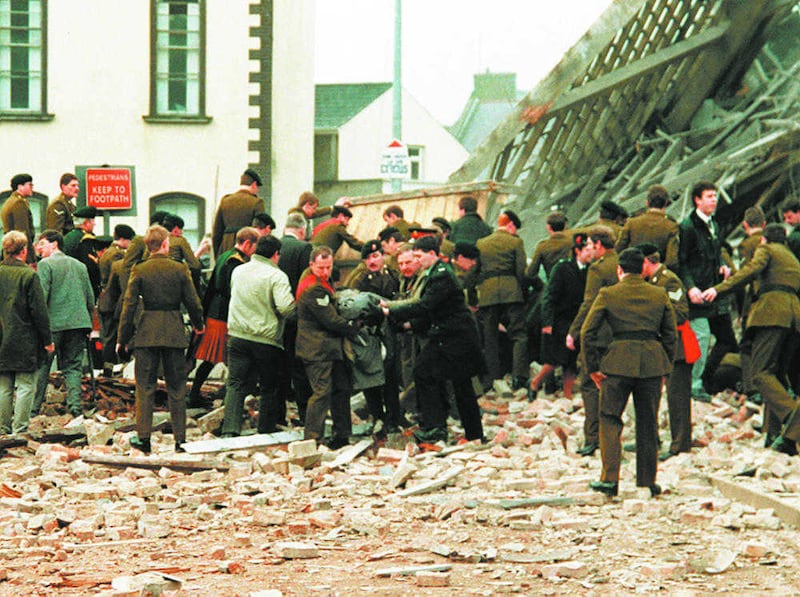

Introduced in October 1988 under the Broadcasting Act 1981, the ban was dreamt up by a vengeful Margaret Thatcher – who narrowly escaped assassination by the IRA in the 1984 Brighton bombing – and primarily aimed at ‘silencing’ Sinn Féin in the wake of IRA atrocities like the Enniskillen bombing.

Also covering 10 other loyalist and republican groups, the ban prohibited broadcasters from allowing anyone affiliated with these bodies to speak on television and radio. Bizarrely, however, a legal loophole allowed broadcasters to circumvent its requirements by simply employing actors to re-record whatever was said.

Thus, instead of hearing Gerry Adams’ voice at a Sinn Féin press conference or media briefing, television viewers would have the slightly surreal experience of hearing an actor’s voice coming out of his mouth, usually slightly out of sync with the movement of his lips, in the manner of a poorly dubbed 1970s kung-fu film.

Indeed, familiar theatrical names like Lalor Roddy, Conor Grimes and Stephen Rea were among the local Thespians who found regular employment in lending their voices to Adams and others on behalf of various local TV and radio news outlets.

Read more:

The ban was finally lifted in September 1994, and 30 years later the whole thing seems utterly surreal. However, as Roisin Agnew’s new documentary The Ban explains, it also seemed faintly ridiculous even at the time, especially compared to the Irish government’s rather more draconian Section 31, part of its Broadcasting Act which completely de-platformed all strands of Sinn Féin from broadcast media from 1976 until early 1994.

“I actually didn’t really know about the broadcasting bans,” admits the Irish/Italian director, who will premiere The Ban later this month at the Docs Ireland festival in Belfast, having previously won its annual pitching competition in order to secure partial funding for the film.

“I was aware of the Chris Morris sketch [from his 1990s satirical news show The Day Today in which a Sinn Féin man is required to inhale helium prior to speaking on camera], but I never actually understood that it was a direct reference.

“I was born after the bans were first started and I don’t remember seeing it [on television]. So it was something that I was kind of quite shocked by when I came across it.”

It was while working as an assistant producer on another project that the London-based Agnew stumbled upon a wealth of archive footage from the broadcasting ban era which piqued her interest in exploring it further – as did current events.

“Around the same time, things were happening in the UK with Brexit and conversations around Northern Ireland,” explains the director, who is currently an associate lecturer on the screenwriting and filmmaking MAs at The London Film School and a PhD student at the Centre for Research Architecture at Goldsmiths University.

“The general ignorance about its history and British involvement just kept being kind of staggering, and I say that in a non-malicious way: as in, literally people [in England] just weren’t taught it in school. There’s ignorance there that is systemic and institutional, and perhaps intentional.

“That, combined with what was happening with the ascent of Sinn Féin both in the north and in the south, seemed like an opportune moment to kind of try to find a way of explaining both of those stories to people.”

In the new film from Erica Starling Productions (Lyra), Agnew interviews those affected by the ban such as former Sinn Féin president Gerry Adams and the party’s former director of communications Danny Morrison, along with journalists like former BBC Ireland correspondent Denis Murray who had to negotiate the rigours and peculiarities of the ban and the Irish voice actors who became regulars at the north’s various TV and radio stations for its duration.

“Really, our big question [with the film] was – and I think it’s everyone’s – how did they think this would be a good idea?”, says Agnew, who was born in Rome to Irish parents.

“But also, why is the voice the main thing you want to remove? The draconian measure that they took in the south with Section 31 was so much more extreme, but there’s a logic to it that makes total sense.

“The idea of taking away just the voice, there’s something a bit more poetic about that – and did it have to do with the fact that the main person the ban was aimed at was Gerry Adams, who has this very distinctive voice?

“Taking that away was a form of de-legitimisation – but then it turned farcical, with the likes of Stephen Rea getting into trouble for doing ‘too good’ an imitation.”

While the methods involved in the broadcasting ban might seem kind of silly and/or quaint 30 years on, the idea of governments manipulating and/or censoring news broadcasts in order to satisfy a political agenda has its roots in Italian fascism and remains very much a 21st century concern.

“If you’re also a lover of cinema, this is such a great story about censorship utilising a combination of cinematic tools and techniques,” explains Agnew.

“Having actors involved immediately adds a level of surreal theatricality, and then you have this absurdist element where actors are having to voice really politically incendiary statements or make excuses for continued support [for the IRA, etc] after really horrific attacks.

“Dubbing specifically has always been cinematic tool associated with fascistic measures. Mussolini, and then Franco were the first people to actually appreciate the power of cinema and the power of cinematic tools in shaping public opinion.

“The idea of breaking apart the contract between voice and image is definitely a kind of anxiety that’s still very present and contemporary – especially around things like generative AI.”