DID you marvel at Clifford’s languid brilliance and sympathise as Davy Fitz lost the rag in Ennis last weekend? Are you happiest watching club games while discussing if Armagh will bounce back against Westmeath, or if Jimmy will keep winning matches against Tyrone?

If you’re like that, ask yourself this: Where would you be, and what would we be, without the green glue of the GAA to bind us together?

Last Saturday evening, before Derry played Galway in the first round of the All-Ireland group stage, the only sound in Pearse Stadium was the fluttering of flags on their poles as a minute’s silence was observed to remember the horrors of The Great Famine.

We all know something about the Famine: How blight caused the potato crop to fail, the starvation of the people, how a desperate father stole Lord Trevelyan’s corn to feed his destitute family from the ballad ‘The Fields of Athenry’…

A million people died in ‘An Gorta Mor’ and a million more were forced to leave on the Famine Ships and they were scattered to the four corners of the world.

What happened to the Irish people between 1845 and 1852 beggars belief: 20 per cent or more of the population either left the country or died. So that minute’s silence in Salthill was a valuable opportunity to pause for thought before the match began.

With the game evenly poised early in the second half, Matthew Tierney spotted Odhran Lynch playing a short kickout and he moved quickly to his right to cut it out. A few seconds later the ball was in the Derry net and Galway never lost the lead - they went on to win by five points.

Matthew Tierney comes from a little place called Oughterard a few miles to the west of Salthill. County

Galway lost an estimated 125,000 (28 per cent) of its population during the Famine and the Oughterard Parish buried thousands of souls while countless others left these shores. Last summer Matthew played for the Sean Treacy’s club in San Francisco which was the eventual destination of thousands of the Irish emigrants who left during and after the Famine.

Many of them would have left Ireland through Derry which was the second largest port for emigration to Canada, the USA and Scotland between 1845 and 1852.

Working class people throughout the country lived from hand to mouth and one failed crop was the difference between life and death.

That was the case long before The Great Famine. In the 1830s there were five partial famines in the Aghaderg Parish in County Down. I recently read an informative article by local historian John Joe Sands on how starving beggars in rags wandered the roads of that locality to the extent that a committee was formed to tackle the issue and it reported how more than 700 individuals ‘lived’ in a state of destitution.

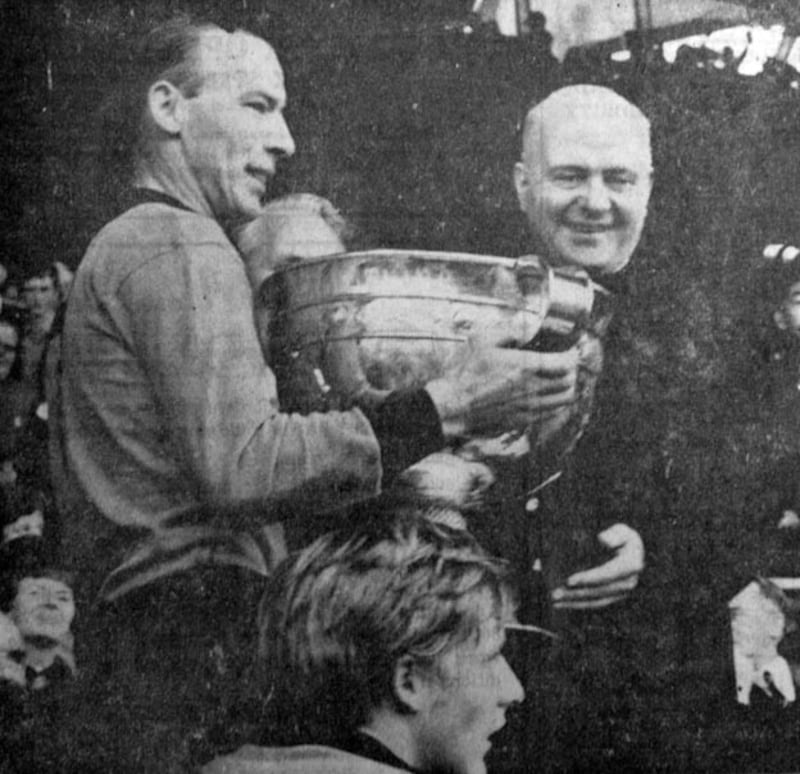

A century later, Aghaderg’s most famous son Joe Lennon was born. Joe won three All-Irelands with Down in the 1960s and captained his county to win the Sam Maguire in 1968. The area remains a hotbed for Gaelic Games today and the rural club between Banbridge and Scarva fields a football team (Aghaderg) and is also home to die-hard hurling outfit Ballyvarley.

It’s a good example of how rural communities have been given a voice and a focal point through Gaelic Games but those games were pushed to the brink of extinction as Ireland’s post-Famine population shrank dramatically due to emigration in the second half of the 1800s.

Hurling dates back through 15th century Donegal chieftan MacOrristan to the time of Cuchulainn and it had prospered before the Famine. But the caman code and the ad hoc Gaelic Football game (known as Caid) came perilously close to dying out.

Rugby, soccer, cricket and hockey spread throughout the country and these ‘foreign’ sports were all encouraged while Gaelic games – viewed suspiciously as unruly and disorganised - were discouraged and even banned by policemen and magistrates as well as by some Catholic clergy and many landlords.

A few areas kept the flame alive. Limerick was a stronghold of the native football game and the Commercials Club, founded by employees of Cannock’s Drapery Store, came up with a set of rules for Gaelic Football and played matches against various sides around the county.

But a way of life was under threat, an entire culture would have been erased and replaced had it not been for the foresight of Michael Cusack and other like-minded individuals who took it upon themselves to protect our sporting culture.

Thirty years after the horrors of The Great Famine, Cusack formed the Gaelic Athletic Association for the Preservation and Cultivation of National Pastimes and Ireland began to recover.

We all have our gripes, it can drive us up the walls sometimes, but what an amazing organisation the GAA is at home and abroad.

You would have to be in a very remote corner of this world not to have some sort of access to a GAA club and J1 visa holders are already setting off to join clubs in the US, the Middle East and Australia this summer. Closer to home, the All-Island Gaelic Football Championships played on Arranmore on Saturday remind us how we are drawn home to represent our native sod and play our native Gaelic Games.

In Salthill last Saturday, the action took over and it swayed one way and then the other until the Tribesmen won the day but that minute’s silence gave it all a sense of perspective.

Whether it’s county or club, little else matters when that ball or that sliothar is thrown in but it’s no harm to pause now and again and think of those who went before us.

And how something so precious to us could so easily have been lost.