In recent months our Churches, in our own particular ways, have been giving thanks for what you might call the ‘coming good’ of creation. The season of Creation in the Catholic tradition and Harvest Thanksgivings in the Church of Ireland have celebrated the abundance and variety of nature and the welcome cycle of seed time and harvest.

Some, however, refer to this time of the year as ‘the fall’ - a description which brings to mind the part of the creation which perhaps finds it most difficult to come good - the human element. Having minds and wills and consciences of our own is both our glory and our vulnerability.

This season “of mists and mellow fruitfulness”, of the changing of the clocks and the falling of the leaves, invites us to consider how the lives of societies and nations - and our own lives - can also “come good” or at least be on a steady trajectory to do so.

All over the world governments are coming and going. The EU, UK, US and imminent Irish elections are among many across the globe this year; around four billion people will have exercised their electoral franchise in 2024. Recently the Irish Church Leaders’ Group made a short visit to Brussels where we met some of the new faces following the recent elections to the European Parliament.

Read more: Archbishop Eamon Martin says churches could help with Troubles truth recovery process

We also encountered familiar faces, including Maros Sefcovic who retains a brief in the Commission for UK-EU relations. In a long meeting we found him to be very engaged and with a detailed knowledge of the situation in Ireland, north and south. Like us, he is keen to see that the Windsor Framework and Safeguarding the Union deal are used in good faith to rebuild relationships and jointly iron out the issues which will continue to arise as a result of the complications of Brexit.

Against such a background of global political change and upheaval, perhaps it is no harm that our own assembly and executive are not so new. Instead they are working out a mandate which the parties were given three years ago. Now they have proposed a programme for government to help Northern Ireland ‘come good’.

In the constitutional sense people will have different views about what ‘coming good’ means, yet we can all broadly share the sense of what is for the ‘common good’, to know what it is we need to be getting on with.

The draft programme dares to dream of “opportunity”, “hope” and “partnership”, with priorities given to “people”, “planet” and “prosperity”, underpinned by a “cross-cutting commitment to peace”. Its optimistic tone is a welcome change to the often stagnant and stultifying rhetoric that characterised political commentary here while the assembly was suspended.

The challenge facing all of us is to ensure that our children and young people are educated and cared for in a way that not only gives them opportunities in the job market but which also deepens their humanity and their desire for wisdom. Caring for the sick has always been an important touchstone of a truly civilised and compassionate society. The most tangible and reassuring way of progress on this front would be in shorter waiting lists and meaningful value and respect both for the carers and the cared-for.

At the far end of our human pilgrimage there is also the support needed for those whose life is drawing to a close, whose value as producers or consumers may be deemed to have ended long since, but whose intrinsic human worth and dignity are as great and as sacred as ever.

The draft programme for government does not appear to sufficiently recognise the community and voluntary sectors’ essential contribution to health, education, peace and reconciliation, to the arts, sports and charitable activities

And, of course, nothing can be achieved unless people feel safe and have confidence in the rule of law. We saw just how fragile that can be over the summer when mobs threatened the rule of law, and on occasion took it into their own hands. There is no place for vigilantism or intimidation in a civilised society. The most legitimate concern we can hold is for the safety and equality of our fellow human beings. This is, at root, why the debate around legacy issues remains a continuing cause of immense hurt and frustration.

Our pastoral work brings us into regular close contact with many in the voluntary and community sector who generously offer their gifts, day after day, to build hope and support social cohesion. They are the ‘glue of society’ and we share their concern that the draft programme for government does not appear to sufficiently recognise their essential contribution to health, education, peace and reconciliation, to the arts, sports and charitable activities without which the government’s key priorities will never come good or bear full fruit.

These are people who make a real difference, especially to the most disadvantaged among us, by daring to dream with their eyes open and feet on the ground. In recent years many such groups and organisations have had to suspend their activities or have struggled to survive because their contribution is so taken for granted that they find themselves competing with each other for the funding scraps left over.

Read more: Archbishop John McDowell: ‘Unionists need to engage with a changing world’

In a world of deepening flux, the draft programme for government seeks to reach out and ‘do what matters’. Our task is to not wallow in disillusionment or cynicism but to do our bit to encourage, work and pray for ‘the coming good’. In doing so, it is important to ask ourselves, as Keats once did: “Where are the songs of Spring?”

There are certain ‘goods’ which are only good when they are held in common. Are we a people who respect and acknowledge the humanity of one another sufficiently to stand up for each other’s wellbeing?

Can our institutions rise to the enormous challenges of envisioning a new sort of society, or are they resigned to be a slow motion re-run of the past?

In searching together for the answers to these questions, all of us, as ordinary citizens, must have the confidence in ourselves and in the leaders of political and civic life to give them space to take risks and to dream dreams.

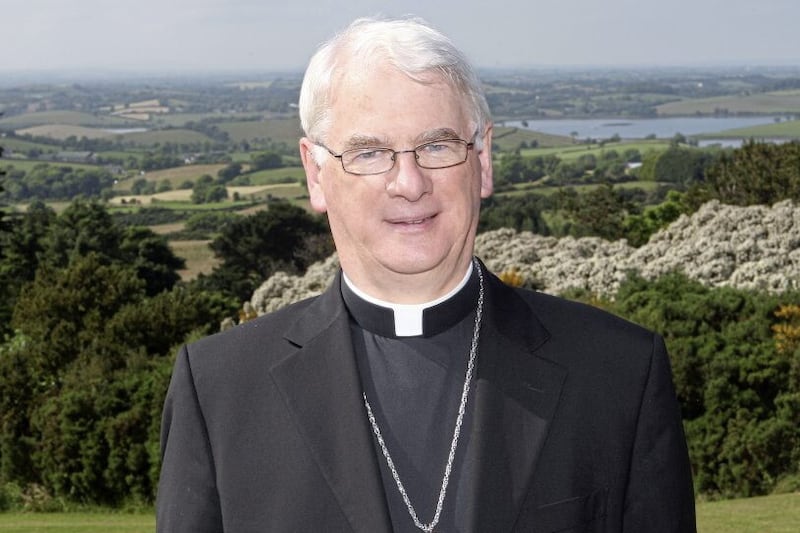

Archbishop Eamon Martin is the Catholic Archbishop of Armagh

Archbishop John McDowell is the Church of Ireland Archbishop of Armagh