The Bluffer believes that we are approaching the time when talk of the Irish language as being tras-phobal - cross-commmunity is becoming redundant.

He knows of no Irish class in which you are asked the question “cad é an creideamh atá agat?” - “What is your religion?” as you walk in the door and people of different religions have been going to Irish classes in Belfast since time immemorial.

For instance, following on from last week, Peter Collins reminds us that many middle-class Presbyterians in late 18th century Belfast were very interested in Irish cultúr - culture, ceol - music and teanga - language at a time when the city had the nickname, the Athens of the North.

“Tionól na gcCuritrí - the 1792 Belfast Harpers’ Festival was a pivotal event bringing together an active Protestant Gaelic group,” he writes.

“Na hÉireannaigh Aontaithe - The United Irishmen saw the language as part of their separatist programme and their newspaper, The Northern Star, published a one-off Gaelic magazine Bolg an tSoláir “(literally “the provision bag”).

Prominent among the Belfast Irish enthusiasts was Dr James MacDonnell, originally from Cushendall, who was involved in every aspect of the cultural and intellectual life of the town. Bhunaigh sé otharlanna fosta - he founded hospitals too.

In 1808, McDonnell, who shied away from the radical Belfast politics of his day, established the Irish Harp Society to tutor blind pupils in the art which shows, the Bluffer believes, that people who promoted Irish were also involved in other forms of daonchairdeas - philanthropy, a trait that has continued to this very day.

Samuel Bryson was a writer and collector of Irish manuscripts and was also a mainlia - a surgeon.

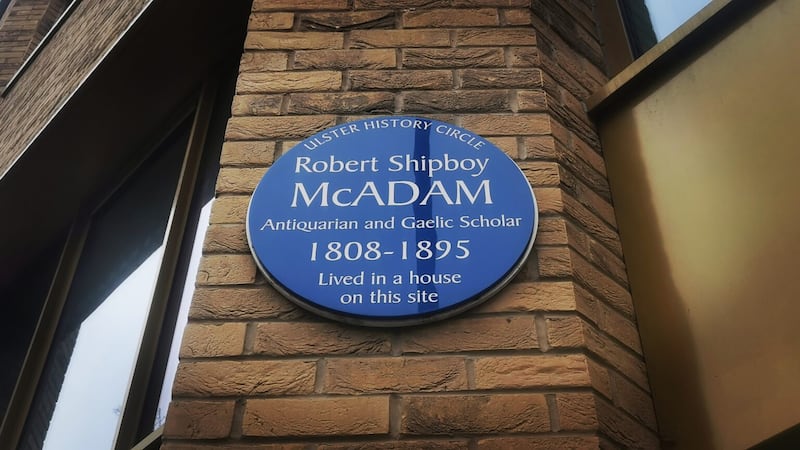

Robert Shipboy McAdam, an industrialist, was a leading member of the many cultural societies in Belfast.

Labhair sé 14 theanga - he spoke fourteen languages but his abiding passion was Irish language, music and seandálaíocht - archaeology.

McAdam made a huge contribution to the industrial and cultural life of the fast-expanding 19th century city and McAdam plastered Belfast with signs with the motto Céad Míle Fáilte - 100,000 welcomes during the visit of Queen Victoria in 1849, which she herself noted in her diary.

Other prominent Presyterians include The Reverend William Neilson, from outside Crossgar, who published An Introduction to the Irish Language, dedicated to an tArd-Leifteanant - the Lord Lieutenant, in 1808.

As Peter writes, this showed that “Irish was not only acceptable but fashionable in a town that was by then strongly unionist.”

Like today, the language is connected with philanthropy – education, community and rural development, job creation and so on.

At the same time, it is about fun - songs, music, poetry etc.

What is there not to like?

You can read the whole of Aspects of a Shared Heritage, the Gael-Linn produced booklet which contains Peter Collins’s article here.

CÚPLA FOCAL

tras-phobal (trass-fubble) - cross-commmunity

cad é an creideamh atá agat? (cadge ay un credgeoo ataa ugut) - “What is your religion?

cultúr (cultoor) - culture

ceol (ceol) - music

teanga (changa) - language

Tionól na gcCuritrí (chunawl na gritcheree) - the Harpers’ Festival

Na hÉireannaigh Aontaithe (na heranee aynteeha) - The United Irishmen

Bolg an tSoláir (bulug un tolaar) - the provision bag

Bhunaigh sé otharlanna fosta (wunee shay oherlana fawsta) - he founded hospitals too

daonchairdeas (daynkhardgiss) - philanthropy

mainlia (manleea) - a surgeon.

Labhair sé 14 theanga (lore shay kera hanga jayg) - he spoke fourteen languages

seandálaíocht (shandaaleeakht) - archaeology

Céad Míle Fáilte (cayd meela faaltcha) - 100,000 welcomes

an tArd-Leifteanant (un tard-leftanant) - the Lord Lieutenant