Michael J Chaplin is recalling how he was frightened of his famous father, the great comedy actor Charlie Chaplin, who “could be explosive”, he says.

“He was a loving father but he could get very angry, he could be explosive. I was a little bit frightened of him. I was nothing like him. I identified much more with my mother. She was a very important force in making me read books.”

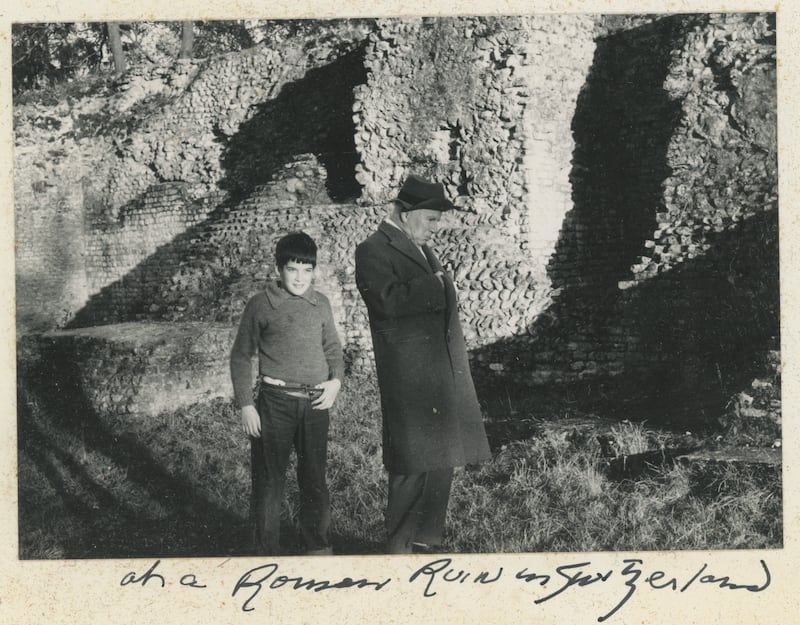

As the second of eight children from the late silent movie star’s fourth (and last) marriage to British actress Oona O’Neill, Michael grew up in a country pile called Manoir de Ban in Switzerland – Chaplin Snr had been exiled from the US in 1952, a victim of McCarthyism, suspected of communism (an allegation he consistently denied).

Michael – who himself has been married twice and has seven children and 12 grandchildren – says his relationship with his father was at times difficult. He looked up to him, but the sheer power and success of the man left his son trying for many years to find purpose.

It has taken him decades to bring his debut novel, A Fallen God, to fruition – and at 77, he says it’s brought him by far the biggest sense of achievement professionally he’s ever had.

The novel is a retelling of the medieval mythical romance of Tristan and Isolde set in 13th century France, told from the perspective of cuckolded King Mark. The love triangle involves passion, anger and loss – emotions the author has experienced at different parts of his life. He can relate to the narrator Mark, who he describes as a dreamer.

“I have never felt very dynamic in acting and doing things, and I think I’ve lacked that kind of energy my father had,” he reflects.

Writing the book was therapeutic, he continues. “I had to come to terms with my anger. It was a great shot of energy to put my own life into it.”

Growing up, he recalls how his father would drum into him the importance of education, which to a youngster with undiagnosed dyslexia who didn’t excel at school was a challenge.

“The great difficulty between him and me was that I couldn’t absorb anything at school. I’d just look out of the window and dream. I couldn’t spell, and he thought this was laziness, until in the 50s they discovered dyslexia.

“He would tell me how important an education is, how your only defence against poverty is having an education. He hadn’t had an education, but didn’t do too badly on no education. His education was in the streets and in music halls. I would have loved that kind of education, not sitting in the classroom.”

Charlie Chaplin was the son of music hall performers, who separated when he was a boy. He hardly knew his father, who was frequently away performing.

“He didn’t see much of his father, he never mentioned him,” Michael recalls. “He talked about his mother a lot, recalling anecdotes about her at the table while we were eating.”

As a boy, Michael was aware of his father’s success, he recalls.

“He took us to Japan, where the overwhelming crowds gathered around him. As a young boy, I went to the opening of Limelight in London. It was overwhelming, with people rushing (forward). I hadn’t seen that in America – I was six when we left – because he worked in the studios and didn’t really involve us in his work.”

He gave Michael a part in one scene in Limelight and then cast him in A King In New York a few years later.

“It was a great experience, because at last I could do something for him and not be the guy who’s last in class. It was wonderful. He gave me all his attention because he needed me. It was a wonderful moment. But it didn’t last.”

At home in Switzerland, his father was a powerful presence.

“When television arrived, he was dead against it. I think he thought television was a terrible thing. But in his old age, he spent all of his time in front of the television,” he recalls, chuckling.

What would Chaplin Snr have made of the digital world we live in today?

“I don’t think he would have got excited about it. He worked with his body, with his physicality, it was a very good language. He was probably for a while the most famous man on the planet, because he could speak every language just by mime.”

Michael gave up on traditional education and left home for London at 16 to pursue a girl he had met on holiday in Ireland, telling his mother he was going camping. The girl’s mother put him up and Michael didn’t contact his parents for some time.

To make ends meet, he did a variety of jobs, from selling fruit and vegetables to decorating parties for debutantes. For a while, he became a pot-smoking hippy living a bohemian lifestyle.

When he returned to Switzerland for Christmas two years later, he says his father refused to speak to him.

“It was my mother that forced him to accept me back. If he wanted to know something, he would tell my mother, ‘Ask him …’ He wouldn’t directly ask me.”

How did being the son of such a successful, famous father affect him?

“I’m sure it’s affected me more than I would admit to, but I try not to let that come into my relationships. Anyway, the kind of people I was moving around with in London were all slightly counterculture. We’d talk about William S Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, we wouldn’t talk about my father’s films.”

He had a brief acting and producing period, and later ran a goat farm for 14 years in rural south-west France.

When Chaplin Snr died in 1977, Michael went through a “big crisis, big depression”. He lost all ambition and entered a vacuum, he recalls.

“My wife and daughters and my son had to put up with that. I was smoking a lot of dope, drinking, doing all those things self-destructively. Luckily, my wife didn’t walk out on me and I was able to come back down on earth – and writing the book helped bring me there. It was a very difficult moment. But maybe you have to go through these moments to be stronger.”

The depression lasted until the death of his mother in 1991, who had struggled since Chaplin’s death. “She tried to have a new life. She painted and redecorated the Manoir in Switzerland, she had friends in New York and Hollywood but ended up back in Switzerland alone in the house, but she couldn’t cope. It was difficult to see.”

When she died, Michael moved back to the house in Switzerland with his brother and his family – there were children running around constantly yet, despite the hubbub, he started writing there. The house has since been turned into a museum.

Michael and his wife Patricia, to whom he has been married for more than 50 years, moved to Malaga five years ago, where they stay in winter. They also have an apartment in Lausanne, Switzerland.

“I’ve never felt belonging to a particular place,” he reflects.

A Fallen God by Michael J Chaplin is published by The Book Guild Ltd, priced £10.99. Available now.