AFTER watching Black Lives Matter protestors in Bristol pull the statue of slave trader Edward Colston from its plinth and deposit it in the harbour, I tweeted: "If the English are going to tear down all the statues of people of questionable character, very few will remain."

This proved prophetic, as a list of similarly disreputable statues now face removal, none more famous than that of the imperialist Cecil Rhodes, which adorns the front of Oriel College, Oxford.

The issue of contentious statues resonates with me for a number of reasons, the first dating back to an experience I had 50 years ago when, as a nine-year-old boy, I attended Pim Street Primary School adjacent to Carlisle Circus.

One morning in 1970 my classmates were proudly comparing our latest haul of war trinkets. My rubber bullet was quickly trumped by a boy with spent bullet casings, whose find was immediately bettered when a boy opened his school bag to reveal four metal toes. Those toes had belonged to the statue of ‘Roaring’ Hugh Hanna, which had stood atop a plinth on Carlisle Circus until a bomb the previous night toppled him.

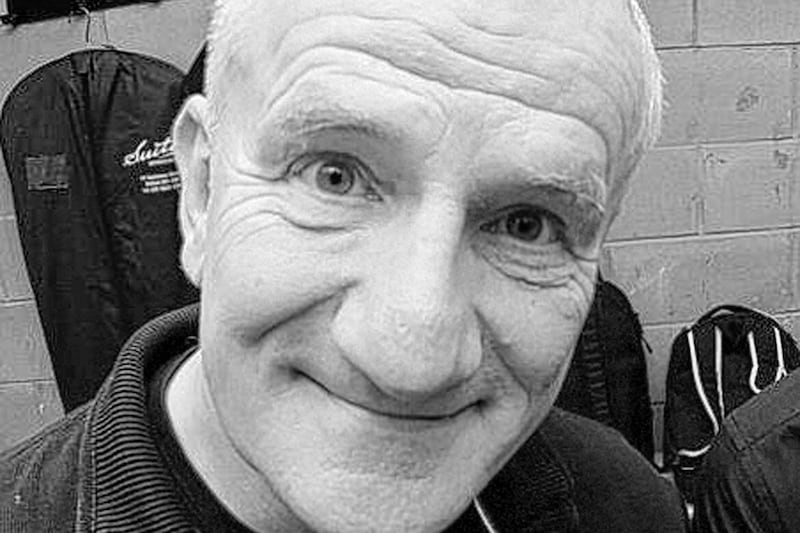

My second connection to controversial statues involves my late father who served as a Belfast city councillor for what was then known as Dock ward in the 1960s. Possessing a wicked sense of humour and no respecter of the pomp and ceremony which surrounded council proceedings, my dad had a regular habit of getting himself thrown out of council debates.

In the early 1960s car ownership had dramatically increased and Belfast faced problems with parking. At a debate on the issue, my father proposed his solution: he suggested the council remove the multitude of, what he termed "useless statues" surrounding Belfast City Hall, allowing the creation of a much-needed car park.

While I can only imagine the uproar which ensued, I do know that, not for the first time, nor the last, my father was ordered to withdraw from proceedings.

I can’t agree with my father about Belfast’s statues. I’m neither in favour of pulling them down nor blowing them up; we shouldn’t let statues join the long list of contentious issues dividing us. Counterintuitively, I suggest we erect more statues, but not of politicians – we’ve enough of them. Instead, let’s erect statues of individuals who’ve excelled in other fields, especially if they originate from minorities seldom memorialised, such as women.

Leaving aside female statues of royalty, the only local statue I can think depicting a woman is the ‘Monument to the Unknown Woman Worker’ erected in 1992 on Great Victoria Street. While commendable, I feel the time has come to recognise an actual local woman, and I believe I have a strong candidate.

In 1967 Dame Susan Jocelyn Bell Burnell, while working as a postgraduate student, made one of the most significant scientific discoveries of the 20th century when she discovered the first radio pulsar.

Born in Lurgan in 1943, Jocelyn Bell faced an uphill battle to progress in her chosen field of astrophysics, which was almost exclusively the domain of men. Having helped construct a massive radio telescope while studying in Cambridge, her thesis advisor, Antony Hewish, tasked the young Bell with the arduous job of analysing the miles of data it produced.

Undeterred with her task of finding a needle in a haystack, the 24-year-old’s tenacious perseverance paid off when she isolated an anomaly in the data, later identified as the first recorded example of a radio pulsar.

So important was this discovery in 1974 that the two professors in charge of the experiment – Antony Hewish and Martin Ryle – were awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics. Despite being the first one to observe the pulsar, there was no official recognition for Bell, a disgraceful omission criticised by many at the time and since.

Refusing to be embittered by the snub, Bell went on to have a glittering career as a physicist, becoming the first female president of both the Institute of Physics and the Royal Society of Edinburgh. In 2018 she received the £2.3 million Special Breakthrough prize for her work on pulsars and a lifetime spent inspiring leadership in the scientific community. Selflessly, she donated all her winnings to help fund studentships for women, under-represented ethnic minorities and refugee students to become physics researchers.

This, I argue, is a woman we can all be proud of and a scientist deserving of a statue, a statue which would elicit inspiration rather than conflict for generations to come.