WITH the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in December 1921, Lord Edward Carson of Duncairn gave his maiden speech to the House of Lords, having being elevated there the previous May, claiming, "What a fool I was. I was only a puppet, and so was Ulster, and so was Ireland, in the political game that was to get the Conservative Party into power."

Many cite this quotation as evidence that Carson was opposed to partition and only realised, when it was too late, that he had been deceived all along by the Tories in dividing Ireland. By reading his entire speech that day, it is clear he was not criticising the Tories for partitioning Ireland, he was criticising them for "surrendering" to Sinn Féin, by conceding too much to republicans in offering dominion status.

He also deplored "the pressure being put on Ulster to join with the south", referencing the attempts made by the British government during the Treaty negotiations to squeeze the already established northern parliament to become autonomous within an all-Ireland parliament from Dublin instead of from Westminster.

Partition was, for Carson, a southern unionist from Dublin, a complex issue and one he struggled with throughout his political career. The ‘guiding star’ of his political life was to keep Ireland united within the British Empire and yet he was arguably the person most responsible for Ireland’s division.

It is important not to read too much into many of Carson’s utterances, as he admitted himself to a Tory backbencher in 1913, a lot of it was "play acting". Using his considerable skills in cross-examination and make-believe that had earned him such a fearsome reputation in the courthouses of Ireland and England, Carson adopted highly theatrical performances in his political campaign to oppose Home Rule.

His stance on the partition of some or all of Ulster, as was the case with many Ulster unionists, evolved during the Home Rule Crisis of 1912-14 from a tactic to a compromise. Partition was no longer the means but the actual end in itself.

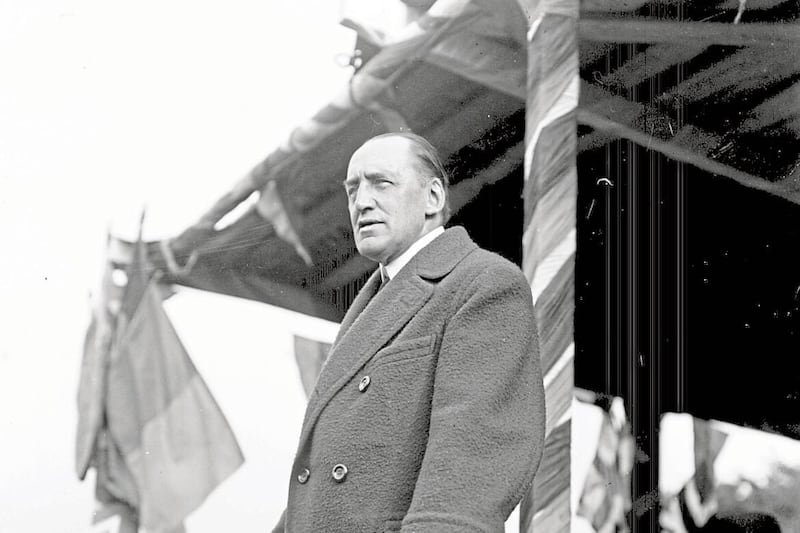

When Carson became the de facto leader of Irish unionism in February 1910, he had very little personal or professional experience of Ulster. Educated in Dublin and Laois, initially practising as a lawyer in Dublin, he had spent the previous 20 years living and working in England. He spent the following 11 years, though, as Ulster’s main champion in opposing Home Rule and has since been hailed as ‘King Carson’, the patriarch of Northern Ireland, with an imposing statue of him at the front of the Stormont Buildings, a clear manifestation of his reverence within Ulster unionism.

While Carson often made contradictory remarks in private on partition, his public stance and ultimately his actions demonstrated that he supported the permanent exclusion of six counties of Ulster from at least 1913. This change in stance was in many ways borne by Carson’s frustration with southern unionists who he felt were not mobilising in opposition to Home Rule in the same way they had during the Home Rule Bills of 1886 and 1893. He bemoaned their unwillingness to take risks, even financial ones, and believed they had become reconciled to the idea of Home Rule.

As Ireland spiralled towards civil war, with Carson leading Ulster unionism’s efforts to militarise, Herbert Asquith’s Liberal government negotiated with Carson and the leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party John Redmond to compromise on Ulster.

Carson rejected Redmond’s suggestion of Ulster being granted Home Rule within an Irish Home Rule parliament. He scorned Lloyd George’s scheme for Ulster counties being allowed to opt out temporarily from Home Rule, famously saying he "did not want a sentence of death with a stay of execution for six years".

Although "in pain and depressed" by his abandonment of unionists in the Ulster counties of Cavan, Donegal and Monaghan, he was unyielding in insisting that six, and not the nine, counties of Ulster be permanently excluded from Home Rule.

Perhaps a prisoner of the "more extreme followers" within Ulster unionism who were "apparently afraid that a big entire Ulster would gravitate towards a United Ireland", Carson still was the unionist who pushed for a six-county solution more than anyone.

Much of Carson’s bellicose rhetoric may have been ‘play acting’ to him but his words often led to more deadly consequences. His confrontational language and his threat of the use of force by Ulster unionism to oppose Home Rule brought Ireland to the very brink of civil war.

After the First World War, his speeches still inflamed tensions and offered little in the way of compromise to try and bring the two main communities together. He, of course, cannot be solely blamed for such division. Post-First World War Ireland was no place for nuance.

His 1920 Twelfth of July speech to 25,000 Orangemen at a field in Finaghy stands out as being particularly incendiary, where in talking about the "invasion of Sinn Féin" to Ulster, Carson stated, "We must proclaim today clearly that come what will and be the consequences what they may, we in Ulster will tolerate no Sinn Féin – no Sinn Féin organisation, no Sinn Féin methods… And these are not mere words. I hate words without action".

Days later the sectarian violence which defined the birth of Northern Ireland started in Belfast, lasting for two years, with the loss of just under 500 lives in the city. Carson’s thinly veiled threat to use arms has to be considered a contributory factor to the outbreak of that violence. The London Times blamed Carson for "having sown the dragon’s teeth in Ireland".

With the introduction of the Government of Ireland Bill which offered a devolved parliament for the new entity of Northern Ireland, Carson complained bitterly to the British government that, where Ulster unionists "wanted to stay with you, and where you had no cause of complaint against them, you still want to kick them out as if they were of no use, to please somebody else".

He still conceded an Ulster parliament had attractions, "Once it is granted…[it] cannot be interfered with. You cannot knock Parliaments up and down as you do a ball, and once you have planted them there, you cannot get rid of them’. He did not oppose the passage of the bill through the Houses of Commons and Lords which paved the way for the partition of Ireland.

Much has been made of Carson’s decision to stand down as Ulster Unionist leader in February 1921 resulting in him not becoming the first prime minster of Northern Ireland, and of his absence at the state opening of the northern parliament by King George V in June 1921, with his wife representing him there instead, as signs of his opposition to partition.

However, in resigning as leader he claimed the only reason he was doing so was because of his age and energy and that he would not be able to "work from morning till night, all day and every day" which was required of the new prime minster. Carson stood down as leader only when a northern parliament was secured.

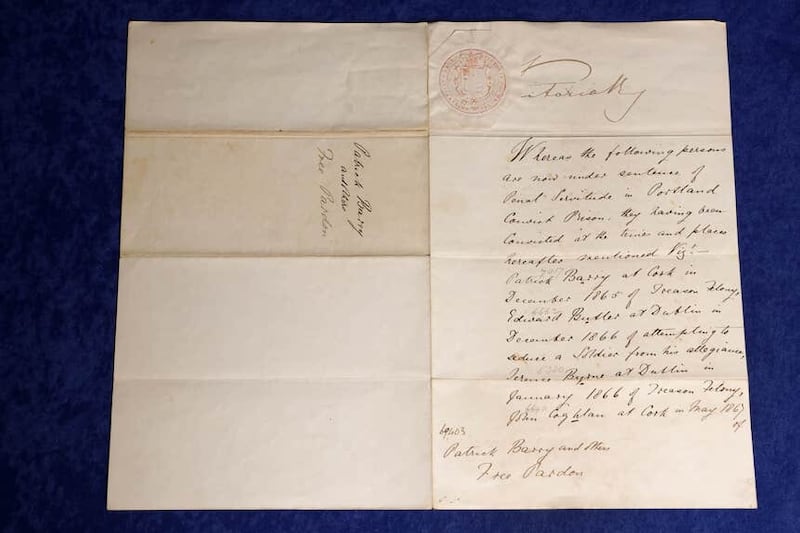

In later years Carson confided to his friend FS Oliver that "[I] feel I am a citizen without nationality or anything to be loyal to". He still asked Northern Ireland Prime Minsiter Sir James Craig that he would like to be laid to rest in Ulster. When he died in 1935 he was given a state funeral and buried in St Anne’s Cathedral in Belfast. As his coffin was lowered into the tomb, soil from each of the six counties was scattered on it. It is clear that Carson desired for all of Ireland to remain within the union, but when this was no longer a realistic option he committed himself wholeheartedly to the exclusion of the north-east from Home Rule.

By cutting through his bombastic rhetoric and his many contradictory and ambiguous remarks, and by looking at his actions as the leader of Ulster unionism when Ireland was divided, Sir Edward Carson has to be considered as the architect of the partition of Ireland.

Cormac Moore is author of Birth of the Border: The Impact of Partition in Ireland (Merrion Press).