THE year is 1858, it is a cold autumn night, with a bitter wind whistling up High Street where the River Farset flows into Belfast Lough. Narrow alleyways branching from High Street are home to the bars, brothels and boarding houses catering to sailors and travellers from around the world.

The next morning, a ship will depart for the United States. Those sailors lucky enough to have been given shore-leave drunkenly stumble back towards their hammocks; they’re joined by passengers, excited at the prospect of setting off for a new life in a new land.

Among the throng of bodies and noise stands a small, immaculately-dressed 89-year-old lady. To ward off the cold, her white satin bonnet is tied tight and her shawl gathered so close around her head that only her nose and round spectacles can be seen, glinting in the gaslight.

As sailors and passengers pass, she quietly presses a pamphlet into their hand. A sailor, thinking it a Bible tract denouncing alcohol, throws it on the ground with a curse.

Undeterred, she slowly bends and picks up the discarded piece of paper, wipes it clean and hands it to the next person who passes. The lady’s name is Mary Ann McCracken and the pamphlets she is distributing denounce not alcohol, but slavery.

While Britain’s ignominious history of slavery ended in 1834, the trade continued around the world. Mary Ann knew many of the sailors she petitioned would be involved in that trade, transporting products from, or slaves to, the plantations of the United States or the West Indies.

So devoted was she to the cause of anti-slavery that she refused to eat sugar as it was a product of West Indies’ plantations. She also knew passengers travelling to the US would become citizens of a slave-owning nation. Mary Ann’s efforts weren’t in vain; she lived to see the end of slavery in the US in 1865, dying in 1866 at the age of 96.

During her eventful life, Mary Ann lived through momentous times and personal tragedy. At the age of 28, she had the trauma of accompanying her beloved brother Henry Joy to a scaffold erected in Corn Market in Belfast, where he was executed for leading the United Irishmen rebellion of 1798. After his death, Mary disappeared from history, for history was then written exclusively by and for men.

We now reclaim a remarkable woman whose views were a century ahead of her time. Going against all societal norms, Mary Ann took in her dead brother’s illegitimate daughter, Maria, raising the child as her own. She became a successful businesswoman, setting up a muslin factory with her sister.

Once again, she stood apart by refusing to sack staff to save costs, saying, “I would not think of dismissing our workers, as nobody else would employ them”. She also campaigned tirelessly on issues such as child welfare, prison reform and the abolition of slavery.

The Belfast Charitable Society recently launched The Mary Ann McCracken Foundation in recognition of her work as a social campaigner. Speaking at it’s launch, historian and broadcaster Prof David Olusoga commented on society’s “…inaction and moral passivity”, believing this “…would surprise and disappoint women like Mary Ann”.

Yet all is not lost; I’ve been encouraged recently by the Black Lives Matter movement and campaigns to address man-made climate change, inspired and led by young people. If Mary Ann’s spirit lives on, it is in them, and with them resides any hope for real change.

Mary Ann is but one of many women almost erased from history, their misfortune to be born the wrong gender.

When I sat down to write this column, I considered condemning the twisted logic of Gregory Campbell, but realised nothing I’d write would be as damning as his own utterances. Instead, I chose to write about a local woman whose long life was spent campaigning against such idiocy and intolerance.

We must not forget those who fought against slavery in the past, and those who fight racism in the present. That she is being lauded not in the News Letter – the paper founded by her father in 1737 – but in the upstart Irish News which opened in 1891 would, I feel, appeal to her rebellious nature.

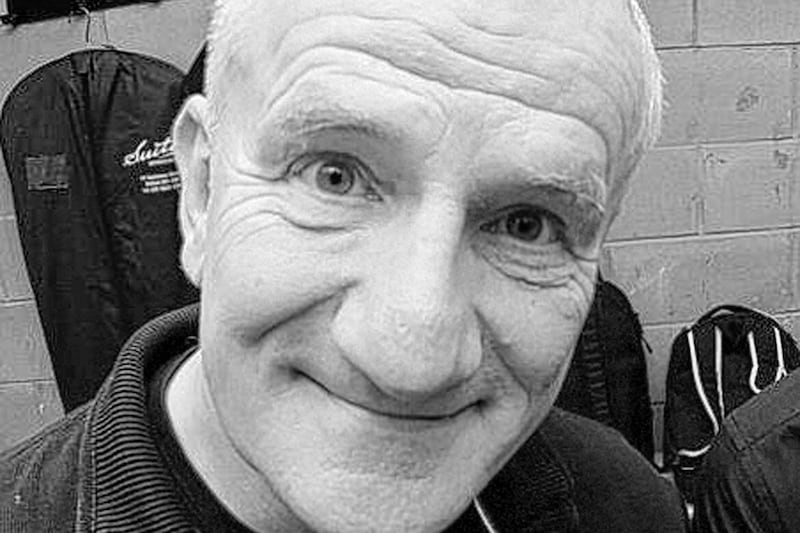

The Mary Ann McCracken staring out from her photograph looks like an innocuous old lady; her eyes, however, shine with the steely resolve of a harbinger not only of feminism, but also socialism, children’s rights, prison reform and the end of slavery.