I'M WRITING this while sitting at a very small desk in a budget hotel in London. I've never understood why people pay over the odds for a hotel which they'll only use as a bag drop and somewhere to sleep.

I'm over with my family for the children's half-term school break. As happened on our last visit, we split up to see different shows: my wife and daughter went again to see the musical Hamilton while I took my son to see a production of To Kill a Mockingbird starring Hollywood actor Matthew Modine.

The suggestion was floated that we all go to see Hamilton but my wife explained to my children my detestation of musicals. She told them how I'd once walked out on her only 20 minutes into a performance of Miss Saigon. She was, of course, being a tad dramatic: while admittedly I did leave the room in which the performance was happening, I didn't leave the actual theatre – instead, I patiently sat in the foyer, reading a newspaper, until the show ended.

To Kill a Mockingbird proved a much better choice for me. While Matthew Modine was passable as Atticus Finch, the late Gregory Peck made that role his own, winning an Oscar for his performance in the 1962 film version. Hollywood glitterati such as Modine find London's West End impossible to resist, but the real draw for me was Aaron Sorkin, who'd adapted the novel for the stage. Sorkin is one my favourite writers with a back catalogue including The West Wing, The Newsroom and A Few Good Men.

Lasting over two hours, the play proved to be 30 minutes too long for my damaged spine: I twitched in my seat like a heroin addict in withdrawal as I vainly tried to find a position to ease the sciatic pain slowly creeping down my left leg.

To add to my discomfort, we were sat in front of a group of Americans who voiced their annoyance at actors they deemed to have less than authentic accents. Normally, I'd ignore such rudeness, but having already reached my pain threshold, I slowly twisted my head around – like the girl in The Exorcist – immediately ending their running commentary.

Harper Lee's 1960 book To Kill a Mockingbird on which the play is based was a searing commentary on both America's overt racism and its love of capital punishment. On the walk back to our hotel, I explained to my 15-year-old son the similarities between the racism of 1960s America and the sectarianism of 1960s Northern Ireland. Even the songs of the protestors were the same with We Shall Overcome ringing out on both the streets of Selma, Alabama and Derry.

Maybe overly-sensitised by having attended the play, I found it jarring the very next day to read a comment from Tory party deputy chairman Lee Anderson, who stated his support for the return of the death penalty, explaining, "nobody has ever committed a crime after being executed".

Anderson's quote is, of course, idiotic. He strikes me as someone who revels in his own ignorance, attempting to cover up his intellectual inadequacy by masquerading as a 'man of the people'.

In truth, he's more a man of the minority of people who view everything English as superior and everything non-English as inferior.

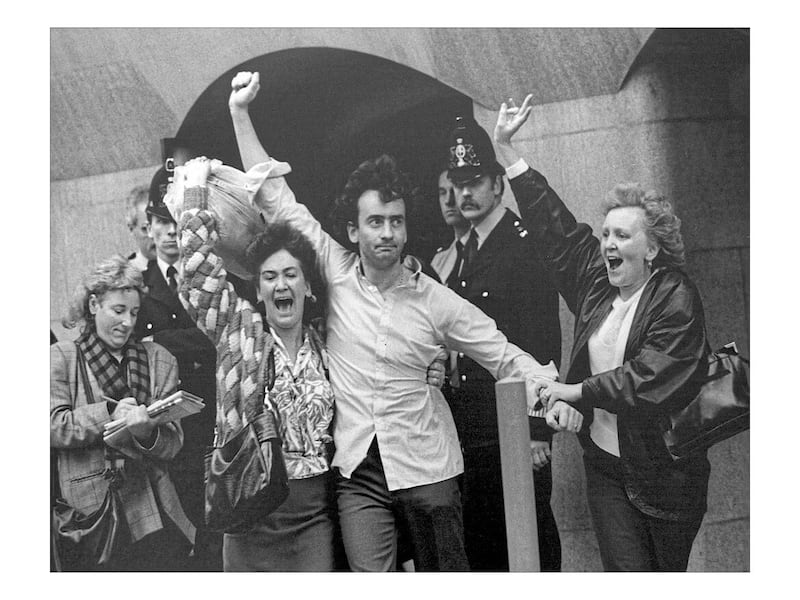

Most residents on this island will have a different opinion on the issue of capital punishment. Those my age will remember the words of Lord John Donaldson who, when passing sentence as presiding judge at the trial of the Guilford Four, said, "if hanging were still an option, you would have been executed".

Thankfully, Donaldson didn't have that option, as 15 years later all four men were proved completely innocent of all charges, as were the Birmingham Six and Maguire Seven.

In total, 17 completely innocent men and women would have lost their lives if the likes of Lord Donaldson and Lee Anderson had their way.

In the USA, 190 people convicted of murder have been exonerated since 1973, and it is estimated that 4 per cent of those on death row today may also be innocent. The perverse logic of governments which continue the practice of capital punishment is that, by murdering people, they will deter others from murdering people.

Capital punishment has never, and will never, act as a deterrent: rather, it reduces the state concerned to a moral equivalence with those who murder.