Fr Chris Hayden: To start with the relationship between Church and State here in Ireland: it's often said that we're growing up as a nation, but I sometimes think we're moving from an infantile deference to the Church, to an adolescent rebellion against it. Is the relationship actually maturing?

John Bruton: There will never be a fixed relationship between Church and State. If you take a long, historical perspective, for the earliest centuries the Church was persecuted, then Christianity became the established religion in the Roman Empire.

In the Middle Ages, the Church was the only body that could do some of the things that are requirements of civilised life.

The monasteries were the nearest thing to a system of social welfare, and they were Church-run.

The state made war, and that was about all it did. This was the case right up until the Reformation.

In Ireland, it's fair to say that after the Act of Union, the Church was the only native-run institution in the country for a hundred years or more, at least until local authorities were set up in the 1890s.

It was the only native institution that provided both material and moral support in the wake of the famine.

The Church became very much identified with the Irish people and the Irish people identified very much with it, and perhaps in some ways that relationship became too close, so that when we gained our independence as a result of the struggles of the 1916-1923 period, the Church endeavoured to make the State almost an instrument of its work.

That was a mistake; it wasn't wise in the longer term. In the short term, it achieved a lot of external compliance with Church teaching, but people didn't internalise why they were doing things, in the way that the Church would have liked them to internalise, and in effect the Church became a vehicle for social conformism.

That wasn't healthy, and what's happening now is that that overweening influence of the Church on public policy is in retreat.

The Church's influence has been in retreat since the 1970s with, first of all, the removal of the ban on the sale of contraceptives, then all that came after that.

I think that what we're seeing is a reaction in public opinion against the past. And it's easy, of course, for people to proclaim themselves shocked by what went on in the past and to have a pleasant feeling of superiority, but the fact is that people today didn't live at that time.

If they had, they might have taken a different view; indeed, we're at risk of replacing one form of conformism with another, equally objectionable, form.

I think it was a famous sports journalist who referred to the Irish people as being like starlings: they're all going in one direction at one time, then suddenly they're all going in another direction.

So yes, I agree with the concern underlying your question.

CH: If you were to sketch the contours of the ideal Church-State relationship, how might it look?

JB: I think that mutual respect is essential. The State should respect religious faith and religious faiths, but they in turn should respect the space that has to be occupied by the State.

The boundary between what is a State responsibility and what is a Church responsibility will shift over time, depending on the resources available to one or the other.

In the early years of this State, the only body that had responsibility for the social services that were provided was the Church and Church-supported institutions.

That is no longer the case, but the situation may change.

The State's capacity to provide services depends entirely on its ability to raise taxation.

Taxation is a coercive activity, but there are limits to it; the State's taxing power may be pushed to its limits over the next 30 or 40 years, by the cost of our ageing society.

It has been calculated that in most European countries, if they continue with the present level of spending and social commitment and the existing potential for tax, instead of having a debt-to-GDP ratio of 80 per cent, we could, by 2050, have a ratio of 500 per cent.

When we gained our independence as a result of the struggles of the 1916-1923 period, the Church endeavoured to make the State almost an instrument of its work. That was a mistake

That's the trajectory on which most European states are actually set at the moment - it's not discussed very much.

If that's the case, one can imagine - just as in the 19th century - private institutions having to take back on some of these responsibilities, because the State will not be able to do it on its own.

In Ireland, there is a very strong tradition of voluntary service, and I think that that emanates either from religious faith or from the residue of religious faith, where people believe they have a responsibility to a world greater than themselves and their own family.

Voluntarism and voluntary service have always been a big part of Irish life, and they may have to take on more responsibility in the future than at the present time.

This is going to be an ebb and flow of responsibilities over generations to come.

CH: Perhaps a part of that ebb and flow is that faith generates something beyond the pragmatic, beyond what can be coerced - that it generates goodwill?

JB: Faith is about eternity; it's about what happens after we die; it's about what makes us human, what distinguishes us from other forms of life; it's about the relationship we have with God.

By any reckoning, these are more important things than the day-to-day business of government, however important that may be.

The day-to-day business is just that: day-to-day. When it's done, it's done - move on to some other problem.

Whereas the Church is dealing with matters of profoundly greater moment. I think a majority of people in Ireland, even though they may practice their religion very little, believe that there is life after death.

I think we see the most notable evidence of that implicit faith when somebody dies, in how people react to that, in a way that points to something above and beyond the day-to-day.

I think that's what the Church needs to speak to; I don't think we should look at the state of the Church in terms of whether its institutional power is on the rise, or falling, or static.

That would be to use the vocabulary of politics, which is a temporary thing, to judge something that is eternal.

I think the Church must have faith in itself, and it must tell people the truth about things that last.

CH: In politics, you have the party whip, and you have conscience. There can be a conflict between them.

JB: I think the party whip is a good thing. We see in Britain how a country can get into a mess when it doesn't have a proper system of party discipline.

I'm very much a supporter of the party whip. And it's important to say that in terms of global politics, the party whip was an Irish invention - of Charles Stewart Parnell, particularly, who introduced the idea of a disciplined party system to Westminster, because as a minority they could be properly heard and defend their interests only if they stuck together and voted in accordance with majority decision.

So as a general rule, I would not be critical of the party whip, but I think there are occasions when it should not be applied, and I think that one such is when it comes to issues which transcend normal political calculation, such as the question of what it is to be human, what is a human life, when does a human life acquire human rights.

I think a majority of people in Ireland, even though they may practice their religion very little, believe that there is life after death

Those profound questions do not admit of bargaining or compromise. They arose in the context of recent episodes of legislation to do with abortion in this country, and I think the party whip ought not to have been applied in those circumstances.

CH: What are the biggest influences on your own political thinking?

JB: I come from a constitutional nationalist family, who would not have supported the use of violence at any stage in the endeavour to built a new and better Ireland.

That's an influence on me, and it's a tradition that has been downgraded in a lot of Irish historiography, which has glorified the blood-sacrifices, the ambushes, the shootings that were part of the struggle between 1916 and 1923, and the civil war that was inevitable.

Once you declare an absolute right to a 32 county republic, and you don't achieve it, and you use violence to get there, civil war becomes inevitable.

I strongly support the view that if we're ever to make progress in this country, we'll make it on the basis of peaceful cooperation with other countries and peaceful resolution of any internal differences we have ourselves, or with our neighbours.

In my view, that's the path we should have stayed on, the path of Daniel O'Connell, Parnell and John Redmond.

CH: It has often struck me that Daniel O'Connell is, even here in his own country, one of the most unsung political figures in Europe. I don't understand why we haven't made vastly more of him. We've named a few streets after him, put up his statue, but he's not in the national consciousness.

JB: That's right, and it's because he wasn't part of the physical force tradition. He said that Irish freedom wasn't worth the shedding of a single drop of blood.

He used political agitation instead - mass political agitation. He was the man who, as it were, invented mass demonstration undertaken by disenfranchised and illiterate people.

Remember that most of the people who assembled in Tara and such places could not read, and virtually none of them had the vote.

Yet they were able, simply by coming together in large numbers, to influence political outcomes, including Catholic emancipation; and they very nearly obtained the repeal of the Union.

But this was non-violent, and in order to justify violence, others had to denigrate O'Connell.

I don't think we should look at the state of the Church in terms of whether its institutional power is on the rise, or falling, or static. That would be to use the vocabulary of politics, which is a temporary thing, to judge something that is eternal

I think the same fate awaited John Redmond, in order that people could justify what happened in 1916.

Has this anything to do with religious belief? I believe it has: the fifth commandment is a political statement; it's not just about individual acts of violence - it's about collective acts of violence.

CH: Once that ethos of violence is present, it's very hard to change.

JB: What happens once you start to use violence is that it leads to retaliation, and retaliation creates victims on your own side who have to be avenged.

The memory of the dead becomes a continuing impulse towards further violence calculated to vindicate that memory.

One of the difficult things in the peace process was persuading people who had used or were prepared to use violence, and who had friends killed in the struggle, that by making peace they weren't betraying their friends who had died.

Once you start on the road to violence, it's inevitable that you'll reach that situation. And that's why you shouldn't start.

CH: With apologies for the gender exclusive term, what is 'statesmanship', and who is the greatest statesman or stateswoman you have met?

JB: I think a statesperson is somebody who looks a generation ahead, whereas a conventional politician is somebody who looks only an election ahead.

Now there's nothing wrong with looking an election ahead. If you don't look to the next election, and prepare for it, you won't be in politics very long, and you won't be able to do much good for anyone.

So I don't denigrate political calculations that are part of conventional politics, but there's no point in entering political life - a life that is potentially very stressful and wearing - unless it is for some greater goal.

In this country, politics is comparatively clean; self-advancement is not one of the reasons for entering politics - if that were one's goal, one would get into other things.

As a politician, you need to set yourself a longer-term goal.

As for individuals I've met, it's not a consideration that was ever in my mind when meeting people. You have business to do and you get on with the business.

But one of the people who impressed me personally was Fidel Ramos, President of the Philippines. He was a military man who had made peace with Muslim rebels in the southern part of the Philippines.

I admired his interpretation, in our conversation, of what you need to do if you want to make peace: making peace involves putting yourself in the shoes of your enemy, seeing life as your enemy sees it, and trying to find a way of adapting what you are doing, to take account of his or her perspective.

I heard Ramos express that sort of thinking in a manner that was very helpful.

The people decided that a human has no rights until first they are born; pre-birth, humans have no rights. Prior to that, Ireland was one of the few countries in the world which gave a constitutional right to life to a pre-born human, and that's now been taken away

Also, I have a lot of time for Jean-Claude Juncker (European Commission president) and Michel Barnier (EU's chief Brexit negotiator), both of whom I know quite well.

Both of them have done a great deal to build a more cooperative Europe, and I think a peaceful Europe is a building-block of a peaceful world.

We can't solve all the world's problems here in Ireland, but we can make a useful contribution towards solving the problems of Europe.

We should do that, and we should support people like those two men, who have contributed usefully to that.

CH: We're a year on from the referendum on the Eighth Amendment to the Constitution. Despite - indeed, because of - the result of that referendum, the pro-life task is ongoing. The Constitution has changed, and now we have, at least in principle, quite a liberal regime. How do you see the post-referendum pro-life task?

JB: What the people did when they changed the Constitution was reduce, narrow, the scope of human rights, because without the right to life, no other human right is possible.

The people decided that a human has no rights until first they are born; pre-birth, humans have no rights.

Prior to that, Ireland was one of the few countries in the world which gave a constitutional right to life to a pre-born human, and that's now been taken away.

I think we need to keep that in mind. Rather than rely, in future, on criminal law or on the Constitution to protect the right to life, one must in future seek to rely on persuasion.

To persuade people, you have to first convince them that you're on their side; nobody is ever convinced by somebody who is hostile to them, or whom they perceive as being hostile to them or to what they feel.

So the pro-life movement has to try to win the sympathy of those who might make decisions that could involve the ending of the life of an unborn baby, and to influence the climate of opinion, so that it is sympathetic to - and helpful towards - people who decide not to do that.

CH: So the task is not just to focus on principles all of the time, but to take into account a broader human and relational reality?

JB: Yes, there's a broader human and relational reality to be taken into account, but you use that to convey fundamental truths about life prior to birth - truths that are becoming more and more obvious as science advances.

Science is on the side of the pro-life argument, so we must use that, too, as best we can, to persuade people.

In the wake of the Referendum there is probably a bit of awkwardness in people about proclaiming their pro-life opinions.

Nobody likes to be in a minority; human beings prefer to be part of the majority - and that, I think, is particularly the case in Ireland - but we should be willing to speak up, respectfully.

And I would say that in the referendum campaign, although the pro-life side lost, they did keep their dignity, and they maintained a calm demeanour, which is potentially an investment for the future.

The public were not alienated by them, in a way that perhaps pro-life people did alienate people in earlier times, when they had the majority on their side.

I think humility is the first step towards persuasion.

CH: Jean-Claude Juncker recently told Comece, the Commission of Bishops Conferences of the EU, that he had a deep admiration for the social teaching of the Catholic Church.

Even something like the principle of subsidiarity is a profoundly Catholic principle. I think its time is still to come, in a way, as it sometimes seems that regulations get handed down that don't really need to be handed down.

JB: That's true, but we need a balance. Catholic social teaching, fundamentally, is about treating people with respect - treating them justly and fairly, because of our common humanity.

A difficulty with subsidiarity is that it can be used to justify almost anything. It's been used by Eurosceptics in Britain to say that we shouldn't do certain things at European level.

Obviously, Catholic social teaching evolved very much in the late 19th century, as a response to industrial capitalism and its dehumanising effects.

Those particular dehumanising phenomena have ended, but we now have other dehumanising elements, where years of mass communication have seen a lessening of respect for the dignity of the human person and of people's capacity to think for themselves.

There's also the anonymity of modern society, modern urban living, where people can live their lives interacting with other people either over the internet, or briefly in some commercial setting, such as a shop.

What the Church does is bring people together - either every morning or once a week - and that's a huge antidote to loneliness.

The Church and religious practice represent a huge part of the inherited social capital of the Irish people.

Preserving that social capital in an Ireland that has become urbanised is going to be a huge challenge, and it's not something the State is fitted to do.

The State can't create friendship networks or community networks. Institutions such as the Church can rebuild and maintain the social capital of our people.

I hope that the Church will have the resources it needs to do that in the future. And the Church in Ireland shouldn't be afraid to tell the truth as it sees it.

It shouldn't blame, but it should tell the truth - there is a distinction between blaming and telling the truth. So: not to be afraid - not to be afraid to tell the truth. As often as necessary.

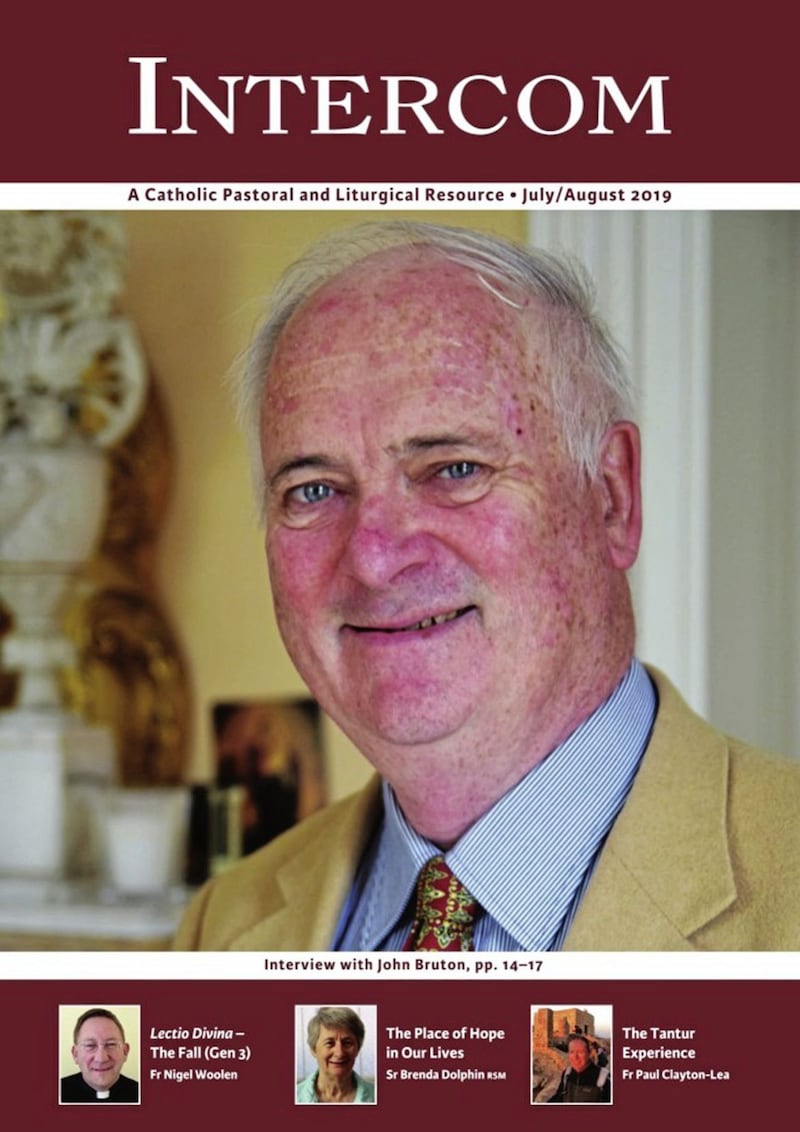

Fr Chris Hayden is editor of Intercom magazine, a pastoral and liturgical resource of the Irish Catholic Bishops' Conference. This interview was first published in the July/August issue of Intercom.