WE live in uncertain times. The Covid-19 pandemic has upended every aspect of how we do things, from school and work to church, sport and anything else you care to name.

Little wonder that people have found solace in prayer and faith. For centuries, Irish people have had a unique relationship with the religious and monastic sites woven into the fabric of the land; at this moment in our history, they seem to offer reassurance and continuity with the past. They hold out the promise of better times to come.

All of which makes a new exhibition of objects linked to Glendalough in Co Wicklow something of a timely oasis of calm in these turbulent days.

'Glendalough: Power, Prayer and Pilgrimage' has opened at the National Museum of Ireland, putting 24 items on display. They span a period of 1,200 years and are all being exhibited for the first time.

Glendalough was founded by St Kevin in the 6th century. Since then it has been a place where people have retreated to seek isolation and healing - both of which strike a chord with our coronavirus world.

"So many themes in this exhibition resonate with the times we are living through - isolation, reflection, faith, and the healing qualities of the countryside," said Catherine Heaney, chair of the National Museum of Ireland.

"Collectively we can take comfort from the endurance of these objects, and of our resilience as a nation through difficult times, past and present."

At the time of St Kevin and in the centuries that followed, pilgrimage was one of the few reasons that the medieval Irish would have travelled far from home. Glendalough was among the pilgrim sites they journeyed to, seeking its healing properties.

And, as well as its religious dimension, Glendalough also became a stronghold of Gaelic Irish families and so developed a political aspect.

Collectively we can take comfort from the endurance of these objects, and of our resilience as a nation through difficult times, past and present

Many of the objects on display were discovered as part of UCD-led research and archaeological excavations undertaken at Glendalough since the 1950s; others emerged through discoveries by members of the public or by donation; collectively, they come together to tell the story of the area down through the ages.

A bronze-coated iron hand-bell, thought to date from the 8th or 9th century, features in the exhibition.

It was donated to the National Museum of Ireland by Archbishop of Dublin Diarmuid Martin on behalf of the diocese.

Ironworking evidence from Glendalough suggests that this bell may well have been made at the monastery.

"Glendalough holds a special place in Irish history and in the history of Christianity," said Dr Martin, who explained that the bell helped to "tell the story of Glendalough as a centre of spirituality for centuries".

Ireland is home to the largest number of hand-bells in the world, and while hand-bells were used to mark regular times for work and prayer, historical sources tell us they were used for banishing evil and cursing people.

A bell dating from the late 10th or early 11th century - making it the earliest in Ireland, and which was suspended for rope-ringing in a belfry at St Kevin's Church - is thought to have been imported from England or north-western Europe.

Exotic objects from distant places reveal the lure of Glendalough. A tiny cross, discovered in 2017 and made of jet originating in north-eastern England, is thought to have been worn by a pilgrim as a mark of private devotion - a rare find in an Irish medieval context.

A fragment of a porphyry tile, quarried from stone in the eastern Mediterranean, is another example of Glendalough's influence.

It was recovered during the excavation of one of the most remote sites in the Glendalough valley in 1958 and is thought to have been taken from a building in Rome or from a Roman building in Europe and carried back to Glendalough by a cleric and used as a mark of authority.

Lynn Scarf, the museum's director, said Glendalough: Power, Prayer and Pilgrimage showed "the connections between our material, natural and cultural heritage and how all these elements are intertwined".

The exhibition also features items such as a shoe from the 10th century which belonged to a pilgrim and which was lost in a bog until it was found by a passer-by and reported to the National Museum of Ireland over a thousand years later; silver coins found as part of a hoard in the 1980s; and decorated cloak pins and pottery.

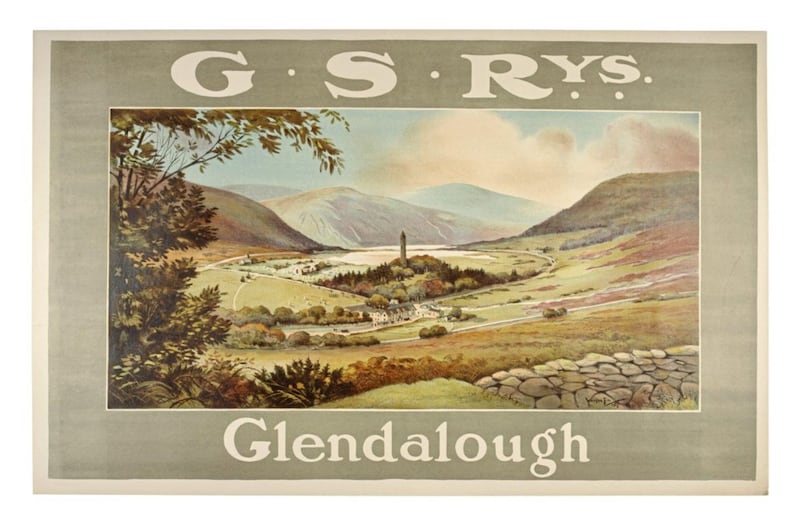

Railway travel posters and souvenir ceramics illustrate how Glendalough also became an important tourism destination.

Glendalough: Power, Prayer and Pilgrimage is at the National Museum of Ireland - Archaeology in Kildare Street, Dublin. Admission is free.