SAINT Paul's letter to the Ephesians touches on the issue of living in a world where there are many differences between people.

St Paul was a Jew, but he was writing this letter to a gentile, non-Jewish, audience. He was trying to teach the Church in Ephesus that in Christ, God had broken down the walls and barriers between people and has given us the means to overcome the hostility that can be present because of differing beliefs.

The letter acknowledges that living with difference is not easy, it requires great effort, humility, gentleness, and patience.

God adopts not a single group with one ethnic or religious identity, but he chooses and adopts a diverse group of people; unity and equality will eventually be found under Christ.

It is a very appropriate message to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the truce that brought to an end the War of Independence in Ireland on July 11 1921.

This had been a two-year conflict that, like many wars, was notable for its acts of brutality.

It is also important for us to acknowledge the role that devotion to St Oliver Plunkett made to bring about peace and the beginning of a process that brought a long sought-after Irish freedom.

The months leading up to July 11 in 1921 were amongst the bloodiest in the War of Independence.

The IRA killed many civilians who they claimed were collaborators and traitors. On the other side, the Black and Tans and the Auxiliaries sought revenge for IRA attacks, doing so in a very harsh and bloody way.

These reprisals, and the general cruelty of these rogue British units, began to turn public opinion around the world in favour of Irish independence.

There were many attempts at peace initiatives undertaken during the first six months of 1921 and some of the most notable ones were undertaken by Church personnel such as Cardinal Logue of Armagh, Bishop Fogarty of Killaloe, and Archbishop Patrick Clune of Perth in Australia.

During 1921 many government buildings were destroyed around the country, including numerous RIC barracks, courthouses, tax offices and other local government offices.

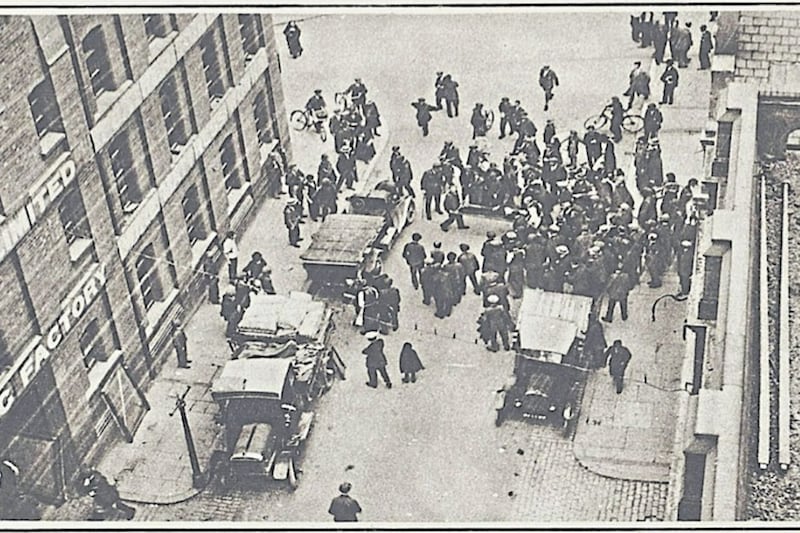

The Customs House was destroyed on the May 25. This was a devastating blow to the administration of Ireland as most of the tax records and local government records were kept there.

This, along with other smaller incidents, made Ireland ungovernable and the war almost unwinnable for the British.

By July 1921 things were descending rapidly into chaos and there was a real risk of a blood bath. Over 1,000 deaths alone were recorded from the beginning of the year and many people were beginning to suffer severe hardship.

Throughout the whole conflict, the Church maintained a strong stance in opposition to the violence perpetrated by all sides, but also used its voice to put increased pressure on the British government to find a solution.

Time and again Catholic bishops, both individually and collectively, asked for prayer and there was a huge response both at home and abroad to their request.

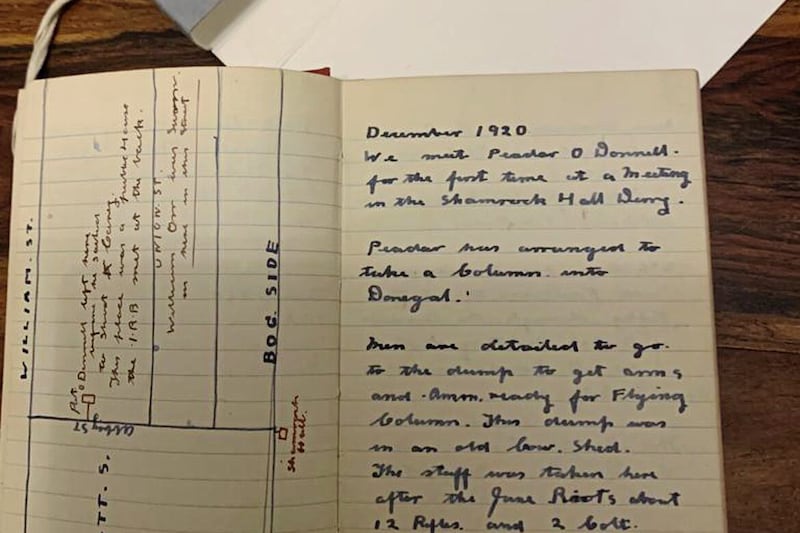

In 1920, Oliver Plunkett had been beatified, the final step before becoming a saint. His beatification was a big occasion for the Irish and many people began praying to him for a cessation of violence and a renewal of peace.

Their prayers finally and remarkably came to fruition with the coming into effect of a truce between the British and the IRA on July 11 - the very first day that the feast of Blessed Oliver Plunkett was celebrated.

Many people came to realise that this was more than a coincidence and that we had gained a powerful intercessor for peace in this land.

St Oliver's feast day changed to July 1 after his canonisation in 1975 and it is to be noted with joy that the first meeting of the new Northern Ireland Assembly, an essential element of the Good Friday Agreement, was held on July 1 1998.

The sharing of power, symbolised by that event, has led to a greater level of cooperation between nationalists and loyalists in Northern Ireland and subsequently to a more stable peace.

As we celebrate the anniversary of the truce and give thanks for all the progress that has been made over the past 23 years in particular, we have to be mindful that the peace in this island is still fragile.

The truce, unfortunately, didn't bring the hostilities to an end. A horrific civil war blew up within months and tensions in the years since have at times led to conflict, terrorism and murder, most notably between 1969 and 1997.

The reluctance over the years by all sides to accept a peaceful solution to the problem of finding a shared identity and purpose have led to many innocent deaths and many shattered lives.

Violence achieves nothing. It is destructive and holds back genuine progress. The violence perpetrated from 1969 onwards held back the progress on civil rights that was being made in the late 1960s.

We pray to St Oliver Plunkett today that those who still advocate violence or who excuse past atrocities will have a change of heart so that we can overcome our differences and know, as St Paul reminds the Ephesians, the freedom that comes from such a change of heart and attitude.

Recent events have shown us that there is a long way to go if all the people of this island are to respect each other and live together without division or violence.

All of us must strive to create a place that will be inclusive and welcoming. A united Ireland, if that is to become a reality, will have to be a place where religious and cultural differences are recognised and protected, not dismissed or ignored.

All of us who want to achieve peace and true freedom will need to be very vigilant and work hard to achieve God's plan for us.

The road to genuine peace, which can only be achieved through the power of Christ and under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, will continue to be a difficult one - but we must never give up.