Almost two centuries ago, a group of Church of Ireland evangelicals came to west Kerry intent on bringing the Bible to the people in Irish.

But within two decades, the evangelical campaign had led to the Kerry Examiner branding the preachers “hypocrites” and “diabolical liars”.

A bitter 1845 libel action against the newspaper, which Anglican clergyman Rev Charles Gayer won, exposed a deep divide between the evangelicals and the Catholic Church.

With the case as his starting point, author Bryan MacMahon said he wanted to trace back to the origins of the evangelical campaign.

The Co Kerry-born retired history teacher, who lives in Dublin, said he was intrigued by the impact of the Anglican missionaries, whose work in the county was seen as taboo and rarely discussed for many decades.

In 1825, only around one percent of people in Kerry were Anglican.

Mr MacMahon said the Church of Ireland - then the established church on the island and inextricably linked with the landlord class - was not “actively seeking” new members until evangelicals got involved.

“It was the age of the second Reformation, great fervour, great enthusiasm, and so these evangelicals came into the Dingle area with a lot of energy,” he said.

“They also brought with them… the Bible in the Irish language. That was the key to their success and the key to their progress over the next 20 years.”

Mr MacMahon said the evangelicals tapped into Irish story-telling culture and visited workers' cottages to read them Bible stories in the Irish language.

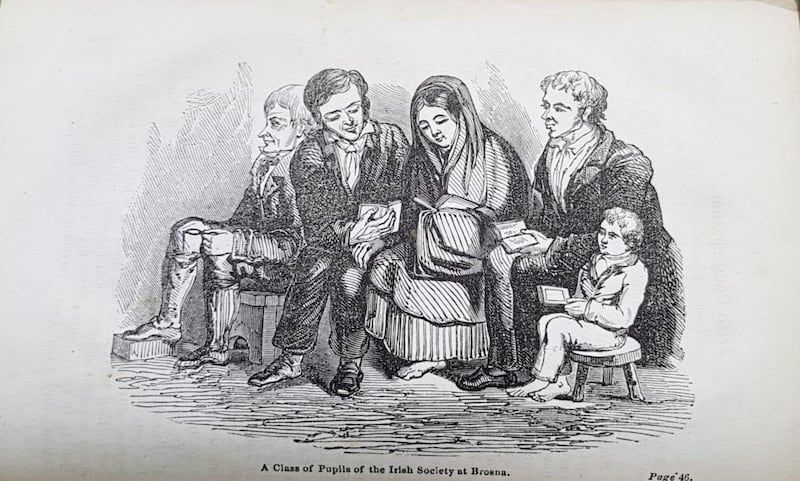

“From hearing the stories… they went on to teaching the people to read the Bible for themselves in Irish,” he said.

“This was very liberating. There were no books in Irish in west Kerry at that time.”

He said the evangelicals were proud of hosting services in Irish had a following “straight-away”.

“They touched people’s hearts at this very innocent, early stage,” he said.

“The teachers were very charismatic people and were able to draw people towards them… I think novelty and curiosity were a big part because for the first time there was an alternative to the existing order.”

He added: “The offering from the evangelicals was very simple. It was read the Bible and make up your own mind.”

Although there was a degree of tension between the more radical evangelicals and the established Church of Ireland, the Anglican missionaries were supported by the Bishop of Limerick, Dr Edmond Knox, and the local landlord, Lord Ventry.

Oppressed by several centuries of penal laws, Mr MacMahon said the Catholic Church was then “emerging from a relatively weak position” and suffered from a lack of priests, most of whom were poorly paid.

“The rituals of the Catholic Church didn’t touch the lives of people as much as it did later in the century or in the 20th century. Weekly attendance at Mass was in some cases as low as 30%,” he said.

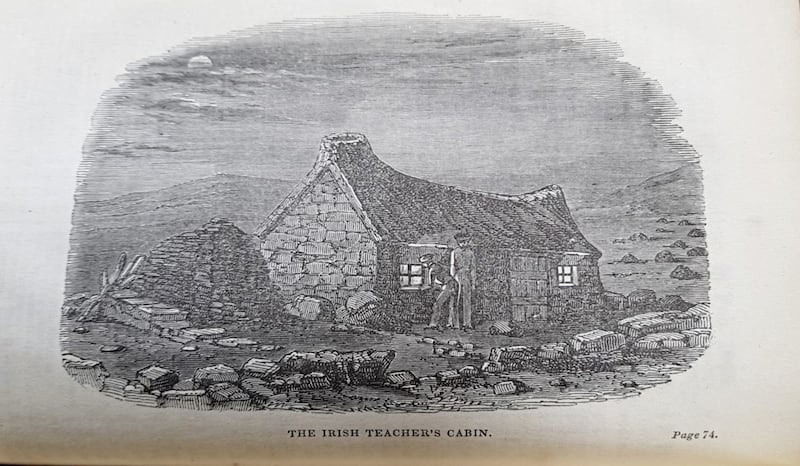

“In a place like the Blasket Islands the priest only visited once or twice a year… When an evangelical teacher came to live among the people he was much more effective.”

While Catholic priests saw the clergymen as proselytisers, the two churches did not come into open conflict until around 1835 when the evangelicals began to build a small number of schools and rectories, including on Great Blasket off the Co Kerry coast.

“The children of local families began to attend these schools and were exposed to evangelical doctrines and were converted,” Mr MacMahon said.

“It moved from a lay movement of teachers and scriptures to a clerical movement.”

He said those who converted were denounced from Catholic pulpits, subjected to boycotts and branded traitors to their forefathers.

“On one dramatic occasion a mother was excommunicated simply because she had sent her child to the evangelical school in Dingle,” he said.

The schools filled an educational vacuum in the area.

Even though the National School system began in Ireland in1831, it took around a decade for it to be established.

“The evangelicals would stand up and say ‘all we want is freedom of conscience’,” Mr MacMahon said.

“They said they were just encouraging a spirit of enquiry… They were very much anti-Roman. When they spoke of Catholics it was the Roman aspect they objected to.”

Mr MacMahon said converts to Anglicanism did benefit financially and were given housing and occasionally work.

“The ministers set up little clusters of converts so they could live in safety and security together… Still today in Dingle and Bantry there are rows of houses called colonies,” he said.

“Compared to the simple housing of people west of Dingle this was an improvement.”

He said the evangelicals were “acutely aware” of accusations they bribed people to convert from Catholicism.

“One of them even said on one occasion ‘yes we do bribe people but our only bribe is Jesus Christ’,” he said.

He added: “It was a case of ‘great hatred, little room’. It was a time of absolutes when there was no room for nuance or any kind of grey. It was ‘we are right and the other side is wrong’. Unfortunately that absolutism led to the conflict.”

Although the book ends before the Great Famine of 1845 to 1852, Mr MacMahon’s work does touch on accusations that those who converted were ‘soupers’ who did so for financial gain or to obtain food.

“Soupers isn’t used much today and it doesn’t carry as much weight now but in the 20th century it did carry that negative (connotation)… One writer said it’s a cold wind that still blows from those days,” he said.

Mr MacMahon said he felt the “great majority” of converts did so “for reasons of faith”.

“The book brings these voices to the fore,” he said. “One was a clerk to the parish priest… and he was converted.

"The way he put it was ‘I couldn’t be easy going to Mass and I couldn’t be easy coming away from Mass. The Lord chased me and there was no escaping the Lord.”

Mr MacMahon said the evangelical mission, although relatively successful, never managed to convert more than 10% of the community and did not represent a real threat to the Catholic Church.

However, one high-profile conversion in 1844, that of Fr Denis Leyne Brasbie, a curate in Kilmalkedar, contributed to a toxic atmosphere between the churches.

“One of the most shocking things is that the (Catholic) bishop sent a young curate to be pro-active in countering the work of the evangelicals,” Mr MacMahon said.

“He sent him to Ballyferriter west of Dingle and within eight weeks the young curate himself converted.”

The curate later went on to become an Anglican minister.

Mr MacMahon said the period “left a legacy” and for many decades people were reluctant to talk about it, such was the impact.

“Back then some of the priests issued a curse on that anyone that had dealings with the converts,” he said.

“The curse was to last seven generations. If you take seven generations (of 25 years each) from 1845 it would bring you to 2020.

“A curse back then was solemn.”

Evangelism was not a nationwide movement, but operated in several pockets, including on Achill Island and Kingscourt in Co Cavan.

“West Kerry was very remote. While all this was happening in the Dingle area there was nothing in Tralee,” he said.

He added: “It happened in a little bubble in a way. But against that it did draw international attention because the evangelicals were great publishers and writers and speakers. They went on tours, including to Belfast, to raise money for the cause.”

?Mr MacMahon said he wanted to shed light on a “hidden part of history”.

“I was very pleased to find named individuals on both sides and to bring them back to life,” he said.

- Faith and Fury is available to order via www.wordwellbooks.com