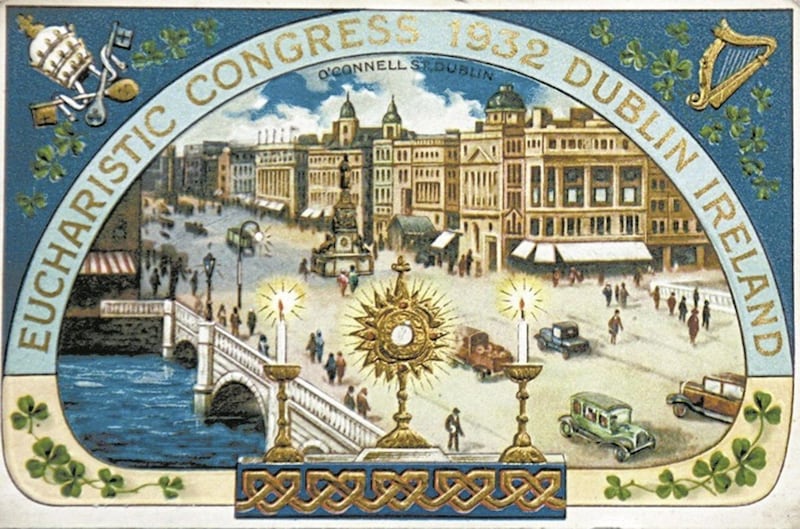

NINETY years ago, in late June 1932, Dublin was chosen to host the 31st International Eucharistic Congress. A defining moment in the Irish state, it was viewed by many as both a culmination of history and a reward for Irish people's suffering for the faith.

While a mere five days in the nation's history, it would have a profound impact upon the direction of Irish life in the following decades. Although largely examined from a 26 county perspective, the congress was also of immense significance to the fledgling northern state.

The involvement of tens of thousands of Catholics who made their way to celebrate with their co-religionists south of the border made the congress an all-Ireland affair. And for those who could not make the journey, an open-air congress Mass in Belfast's Corrigan Park was staged, attracting an estimated 80,000 people who heard open-air broadcasts of the Dublin proceedings.

The Belfast congress Mass was a significant event in its own right. While no restrictions were placed upon northern Catholics in the practice of their religion, the state had, in its decade of existence, already garnered a reputation for religious intolerance.

Therefore, celebrating in this culturally Catholic gathering in such numbers was something of a novelty. However, any novelty value which the event brought was quickly offset by more familiar problems, as the wider congress became the catalyst for sectarian flare-ups across much of the north.

It is unclear if the potential for conflict in the north was anticipated as preparations got underway in Dublin. It was certainly known that thousands would make the cross-border journey to the gathering. And keen to help bridge the longstanding divides, congress organisers sent invitations to attend across the board, including to political unionist representatives in the north.

These invites, sent to Minister for Home Affairs, Dawson Bates, on March 6 1932, were met with mild confusion, and showed that a 300-mile porous border might as well have been a 50-foot-high wall.

Unsure of how to even construct a reply, it was ultimately decided that ignoring the invite was the best course of action. While a veil of silence was deemed wise in government buildings, the approach was not replicated on the municipal level.

Members of Belfast Corporation had also been extended invitations to attend and were, unsurprisingly, accepted by the Catholic members of the council. Nevertheless, their indication that they would attend in their official robes of office proved contentious and elicited a swift response from Protestant pressure groups in the city.

A perceived act of disloyalty to the state, the Corporation's decision led to a hastily arranged meeting of the Belfast County Grand Orange Lodge on May 26 1932. Discussing what was seen as an unsavoury development, the following resolution was passed: "As a Protestant Organisation we feel compelled to register an emphatic protest at the action of the Belfast Corporation in giving permission to Aldermen and Councillors to wear their Robes at the forthcoming Eucharistic Congress in Dublin and thus representing in an official capacity the Belfast Corporation.

"We feel that the presence of these Aldermen and Councillors' robes will be taken as an indication that Protestant Belfast is weakening in its attitude to the idolatrous practices and beliefs of Rome."

Mustering support for the loyal orders' position, Ulster Protestant League posters appeared in various locations across the city. Addressed to the 'Protestant People of Belfast', the posters asked: "Why be represented at the Dublin Eucharistic Congress by Roman Catholic members of the Belfast Corporation who have obtained permission to wear the official robes in a country hostile to the King, Commonwealth and Protestantism?"

Pressure began to be applied to the Lord Mayor of Belfast, Sir Crawford McCullagh, to reverse the decision. A letter from the Ulster Protestant League's Mr H Niblock informed that a resolution was passed in a crowded Ulster Hall on May 29 condemning the Corporation's decision. Demanding that it be quickly rescinded, Niblock promised "your reply and the resolution will appear in the press".

Unbowed, McCullagh did not stand in the way of Belfast Corporation members attending the Dublin event. Nevertheless, similar issues arose in the Derry Corporation where Catholic members were prevented from joining their robed Belfast colleagues.

A motion on the issue was defeated by 10 votes to nine, with unionist members citing the refusal of nationalist members to attend the previous year's armistice commemoration in their official robes as justification of their actions.

The decision was enough to prompt a walkout by nationalist members of the Corporation, and for local newspapers to decry 'Religious Bigotry in Derry'.

In echoes of more recent times, political theatrics played a strong hand in raising the temperature, leading to the inevitability of confrontation on the streets.

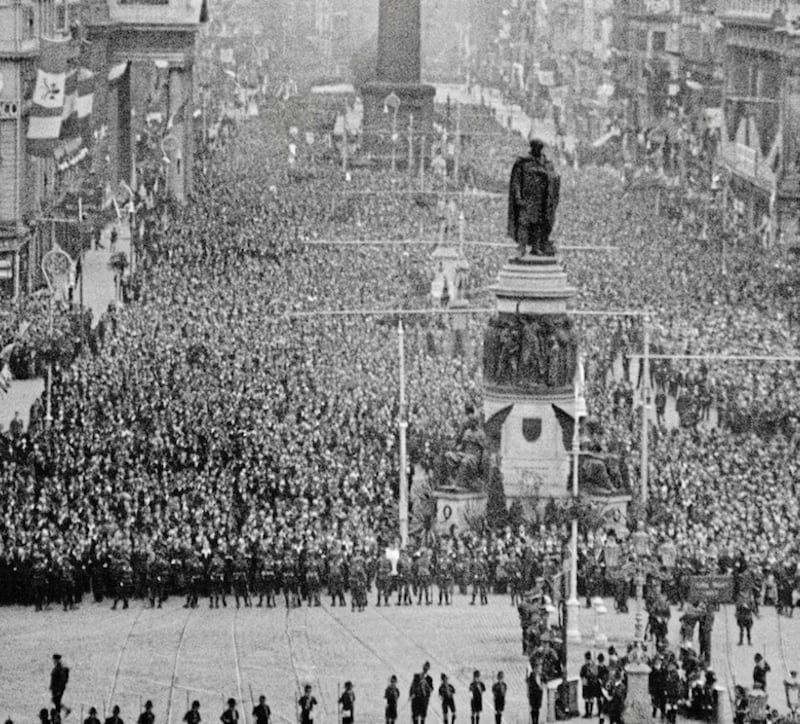

With an estimated 100,000 pilgrims making the cross-border journey to the temporary centre of world Catholicism, it was perhaps inevitable that there would be some incidents of confrontation. Long-planned journeys were made throughout Congress week.

However, it was the finale celebrations on June 26, an open-air Mass in Dublin's Phoenix Park, which witnessed the largest numbers of northern pilgrims departing from across the six counties.

What was a highly anticipated pilgrimage quickly descended into chaos, as groups of early morning travellers came under attack from loyalists who had gathered in numbers at several key departure points.

In Larne, a large group of travelling pilgrims who had chartered a steamboat to take them along the east coast came under a ferocious and sustained attack from a crowd of 150 loyalists. According to two local priests, Fr Bernard MacLaverty CC and Fr Peter Kelly CC, police permitted the loyalist crowd to assemble in the immediate area of departure, where they proceeded to attack the Catholic travellers. The attack, MacLaverty and Kelly claimed, went unchallenged by local police.

Writing to their superior at Larne Parochial House on June 29 1932, the priests stated: "At the scene of attack police were observed standing inactive while showers of stones rained past them upon the pilgrims.

"At the quayside members of the mob advanced even to the ship's side and insulted the pilgrims going on board, while the police, even when requested by one of the priests in charge, did not remove them."

Similar incidents right across the north were reported that evening, and quickly hit the headlines in both the Irish and British press. Locally, the News Letter noted a sustained attack on pilgrims who were making their way to the Great Northern Railway Station. According to the paper, a loyalist crowd from Sandy Row attempted "to surge into Roman Catholic quarters" but were repelled by police.

According to the Irish Examiner, reporting on the same incident, upon forcing the crowd back, police were jostled and called "traitors". Further along the same stretch of road, it was reported that a crowd of approximately 200 youths with Union Flags and a Lambeg drum blocked the path of departing pilgrims who were about to board the train.

In Ballymena, a 500-strong crowd of loyalists physically attacked the assembled Catholics with such ferocity that it was estimated that 200 people were prevented from making the journey to Dublin.

Further attacks in Claudy and Coleraine made the headlines, while a sensational attempt to derail a train carrying pilgrims near Armoy was reported with horror by the Offaly Independent.

British press coverage painted a picture of widespread disorder across the north. In Scotland, the Dundee Courier and Advertiser reported numerous attacks by hostile gangs in Belfast, Lisburn and Portadown who "lined the railway banks, sang party songs and hurled missiles at the trains".

The paper also reported incidents of hand-to-hand combat between Orangemen and Catholics who clashed over objections to the erection of Eucharistic Flags in Co Tyrone. Those who made it to Dublin fared little better on the return leg, as the Irish Independent noted that practically all the trains returning to Belfast "were subjected to stoning when passing Portadown, Seagoe and Lisburn".

THE SENSE of outrage that people travelling to a religious gathering could be viciously attacked with little protection from police was relayed in the nationalist press.

The Irish News lambasted those engaged in the attacks, stating that "while one section of the people - drawn from all parts of the world - were united in Dublin seeking divine graces" those of "the Anti-God forces" in "various parts of the Six Counties have chosen to tell the world that they, at any rate, have no use for Religion".

In what was a weak damage limitation exercise, the Ulster government denounced those responsible. A government press release "condemned these cowardly outrages in the strongest possible manner", while the Orange Order also produced a statement, indicating that it was "deeply concerned to learn of the disgraceful attacks". Unsurprisingly, the denunciations were met with scepticism.

The Irish News laid the blame squarely at the political elites of unionism and the Orange Order, claiming that those engaged in violence were the "ignorant puppets" of "their better-educated leaders" who had "never missed an opportunity for inflaming sectarian passions whenever an opportunity arises".

Pressure mounted quickly on the northern government. No arrests had yet been made, while allegations were rife that police had been forewarned attacks were planned yet failed to act.

The Bishop of Down and Conor, Daniel Mageean, wrote to Dawson Bates detailing his concerns at the events and the alleged inaction of the police. Clearly angry, Bishop Mageean's letter claimed that despite possessing a list of names of the perpetrators, police had decided not to act. This, he insisted needed to be rectified and that he would go to the press with the names if no further action was taken.

The sense of anger in the north was matched south of the border, with several local councils debating a reintroduction of a northern goods boycott. In a meeting of Waterford Corporation at the end of June, Fianna Fáil Alderman James O'Donovan expressed horror at the "murderous attacks" and called on the British government to fully compensate the victims and to take the necessary steps to prevent a recurrence of "this cowardly blackguardism".

Another councillor, JJ Walsh, went much further, exclaiming that they should burn or boycott the Orangemen out of the country. In Kerry a few days later, the council, expressing solidarity with their Waterford counterparts in proposing a boycott, accused the northern government of "winking their eyes at the cowardly outrages perpetuated" on northern Catholics.

Talk of boycotts soon reached the northern premier's office. South Belfast businessman Mr EWJ Harvey, upon returning from a business trip to Louth, relayed the feelings of some of his business contacts in the south to James Craig.

In a letter dated June 29 1932, Harvey highlighted the perception that the government was doing nothing in response to the attacks. Noting "the extreme bitterness which exists" in the wake of the attacks, Harvey went on to warn that a boycott was contemplated, something which would be detrimental to small northern firms like his.

Publicly, the government did little to acknowledge any concerns over a proposed boycott, although the matter was raised internally. Their chief concern was the security of the border.

Bates, in a letter to Craig on July 2, expressed his fear that should the border be breached by "men from the south" seeking revenge, disorder could spread to the cities of Belfast and Derry.

Revealing an extreme paranoia about the neighbouring state, Bates claimed that numerous points along the border were particularly vulnerable to attack. Arguing that while nothing could prevent that happening, he had the option of deploying 'B' Specials, and, as a last resort, British troops.

AN INVESTIGATION on the disorder was ordered by the government to shake off allegations of police incompetence and collusion with the attackers. The report, published on July 8, considered the various flashpoint areas across the state.

Containing much detail on the various locations of confrontation, the report found that in Belfast matters had remained quiet until late on the June 25 when "a rowdy element" appeared on Great Victoria Street where approximately 35,000 pilgrims were leaving for Dublin.

In opposition to a multitude of other reports, the government investigation claimed that disorder only occurred after the pilgrims had departed, with windows being smashed and some looting occurring.

Regarding Larne, the site of some of the most serious disorder, the report found that while approximately 500 people took police advice to depart early for the congress, 700 more pilgrims "insisted" on parading through the town, with "the sight of this unusual procession" having "an unsettling effect" upon "an unruly element of the Protestant side".

That "unruly element", the report later demonstrated was several hundred strong. At the port of Larne "an immense crowd" also gathered and stoned the departing Catholics. The report noted that all available police pushed the crowd back, deeply conflicting with Bishop Mageean's assessment.

Other flashpoints were highlighted, including Ballymena, Lurgan, Lisburn and Portadown. Nevertheless, the report found that there was no evidence of police culpability, a conclusion which did nothing to satisfy nationalists.

On July 26, in the wake of the report, Bates again raised concerns with Craig, this time regarding sentences which were to be handed down to those arrested. Again, Bates's siege mentality was evident.

Calling for lenient sentences for those involved, the Minister for Home Affairs argued: "I do not want when the new Parliament House is opened, or when, on the other hand, we might be engaged in very violent disturbances in connection with the Free State, to have the Government handicapped by having 70 or 80 young fellows in gaol."

The much-feared attack from the Free State, of course, never materialised. Over the next years the northern government had to contend with further periods of street level violence, including the Outdoor Relief strikes, and the ferocious violence in the summer of 1935 which left several dead. This short, but bloody period of violence dwarfed that of the congress attacks and overflowed into many parts of the Free State, where reprisal attacks against innocent Protestant Irish citizens took place.

The 1932 Congress, however, was a defining moment, not only for the Free State, but right across the island. For the south, it was the solidification of an emerging Catholic identity. In the north, it exposed the surface-deep fissures which existed in society and demonstrated to the minority community their place within that society was far from secure.

Barry Sheppard is a PhD Researcher in History at Queen's University Belfast and hosts History Now on NVTV.