IF you are a car fan of a certain age, there is every chance that your childhood bedroom wall was covered with posters of Ferrari's iconic F40.

The 1980s saw an arms race between Ferrari and Porsche, with its 959, to build the ultimate high-tech supercar.

Where the 959 was urbane and every-day usable, thanks to its 911 derived cabin, computer controlled suspension, four-wheel-drive and incredible speed, the F40 was a raw, unadulterated race car for the road.

Both cars have proved hugely influential and gone on to shape the companies that created them.

For sheer drama, however, the F40 still beats the 959 hands-down.

It has a special place in that special company's history, being built to celebrate the company's 40th birthday and the last car designed and launched with Enzo Ferrari's imprimatur.

It was a definitive car - the ultimate expression of the technology of the time, but also a throwback to Ferrari's roots when racing cars were also road vehicles.

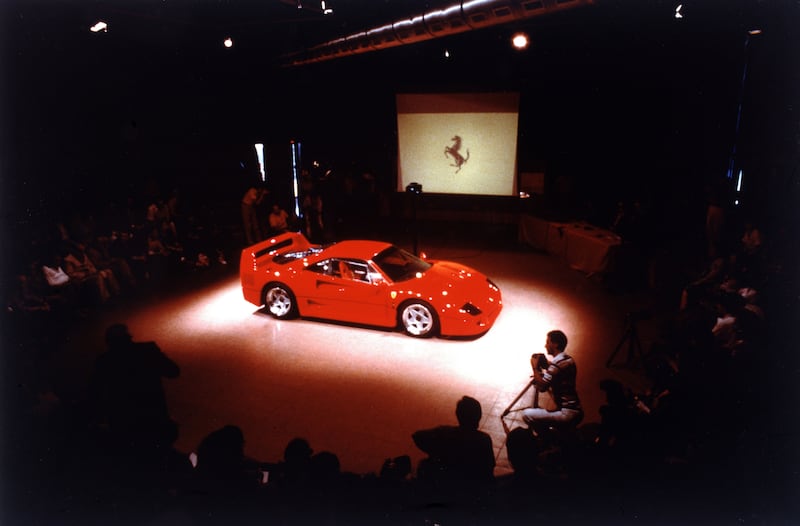

The F40 was launched on July 21 1987 at the Civic Centre in Maranello, which is now home to the Ferrari Museum.

Thirty years on from the launch of an icon of performance and style, here, in their own words, are what three men involved in the F40 project remember about its creation.

Ermanno Bonfiglioli, head of special projects: "I have never experienced a presentation like that of the F40.

"When the car was unveiled, a buzz passed through the room followed by thunderous applause. No-one, except for close associates of Enzo Ferrari, had yet seen it.

"Indeed, the company had cloaked the development and testing of that car in unusual secrecy. And the surprise at such a stylistic leap was almost shock.

"The timeframe was also unusual, within the very short arc of 13 months, the chassis and bodywork moving ahead quickly and at the same pace as the powertrain.

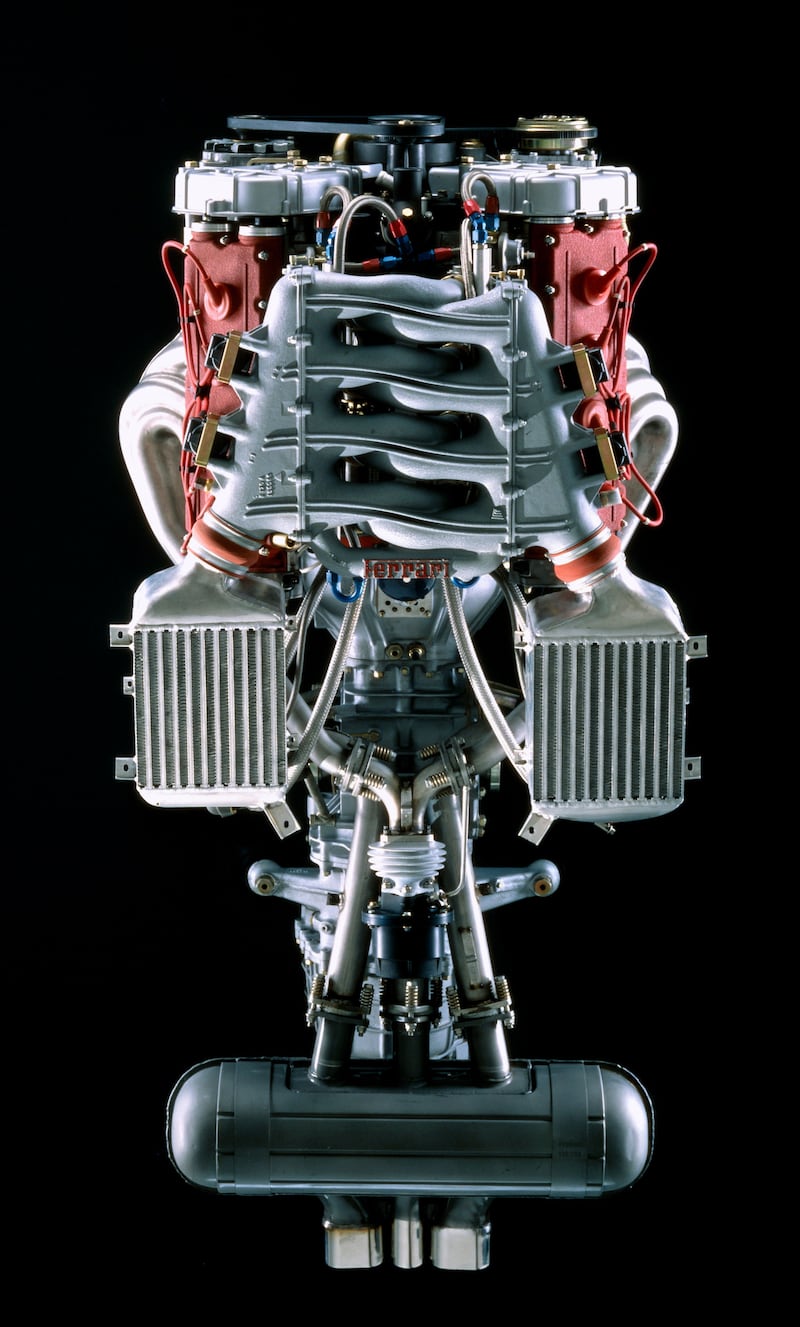

"It was June 1986 when we began designing the engine of the project F 120 A. The 8-cylinder 478hp twin-turbo was a derivative of the 288 GTO Evoluzione’s, but a number of innovative contents enabled the F40 to become the first production Ferrari to exceed 200mph.

"We paid maximum attention to the weight of the engine, thanks also to the extensive use of magnesium, such as oil sump, cylinder-head covers, intake manifolds, and gearbox bell-housing were in this material that cost five times as much as aluminium alloy and that was never used in such quantities in subsequent production cars. This is just a small example of this car's 'difference'."

Leonardo Fioravanti, a designer at Pininfarina: "When il Commendatore asked for my opinion on this experimental prototype [the 288 GTO Evoluzione], which due to regulatory issues never went into production, I didn't hide my enthusiasm as an amateur driver for the incredible acceleration of its 650hp.

"It was then that he first talked to me of his desire to produce a 'true Ferrari'.

"We knew, as he knew, that it would be his last car. We threw ourselves headlong into the work.

"Extensive research at the wind tunnel went into aerodynamic optimisation, to achieve coefficients appropriate for the most powerful Ferrari road car ever.

"Its style matches its performance: the low bonnet with a very tiny overhang, the NACA air vents and the rear spoiler, which my colleague Aldo Brovarone placed at right angles, made it famous.

"If I had to point out one overriding reason for the success of the F40, I would say that its line succeeded in instantly transmitting the exceptionality of its technical content: speed, lightness, and performance."

Dario Benuzzi, Ferrari's long-term test driver: "The handling of the first prototypes was poor.

"To tame the power of the engine and make it compatible with a road model, we needed to subject every aspect of the car to countless tests: from the turbochargers to the braking system, from the shock absorbers to the tyres.

"The result was an excellent aerodynamic load and high stability even at high speed.

"Another important aspect was the tubular steel frame with kevlar reinforcement panels, which provides three times more torsional rigidity than that of other cars of the period, and a bodywork made mainly of composite materials that reduced weight to just 1,100kg.

"We obtained precisely the car we wanted, with few comforts and no compromises.

"With no power steering, power brakes or electronic devices, it demands the skill and commitment of the driver but generously repays it with a unique driving experience.

"Steering precision, road holding, braking power and intensity of acceleration reached unmatched levels for a road car."