Once Upon a Time in Northern Ireland, BBC 2, Monday and iPlayer

It’s difficult to judge a programme that wasn’t made with you as the intended audience.

Once Upon a Time in Northern Ireland is really an attempt to explain to the British what happened during the Troubles.

"It’s definitely made for an English audience that might have fatigue and a wilful apathy about the Troubles, which is shameful," director James Bluemel told The Irish News.

Speaking elsewhere, Bluemel said that for the English, the Troubles may have been “too complicated … (in that) we don’t really understand it and it has nothing to do with us”.

“But this was not a sectarian civil war, it was a three-sided triangle with the UK government on one of the sides so there should be an interest. I hope this series is accessible enough to create that or at least shed a bit of understanding and light on it,” he added.

The director of similar programmes on Iraq and Syria is also targeting a US audience, with the show going out on PBS simultaneously.

To keep it accessible, and in his style, Bluemel focuses on the individual stories from all sides of the conflict.

We get interviews with republicans, loyalists, soldiers, civilians, victims’ families and artists, but pointedly, no politicians.

The viewer gets very little context as the participants explain their personal experiences.

The five-part series runs chronologically with the interviews continuing across the episodes and through the years.

In an unusual device, Bluemel decides to only introduce the characters gradually and therefore the viewer is left to work out the background of each interviewee.

We begin in Derry with the civil rights protests and the excitement of teenage boys at early rioting. Things get very serious quickly as we jump forward to the horror of Bloody Sunday.

Northern viewers will recognise many of the interviewees.

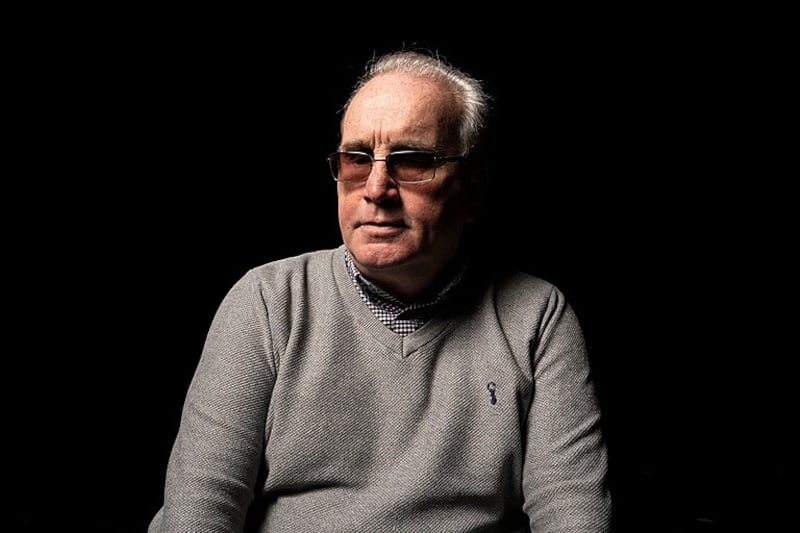

Richard Moore, who lost his sight to a British army plastic bullet in Derry; Kate Nash whose brother was murdered on Bloody Sunday; IRA man and press officer for the 1981 hunger strikers Ricky O’Rawe; and Michael McConville, son of Disappeared victim Jean McConville.

But there are many others with important accounts of the conflict.

Tom, a British army soldier, who was seriously wounded by a bomb planted in a low wall.

He’s embarrassed now as a video of him at the time is played.

Asked how he felt about Catholics by a TV crew in the early 1970s, he says: “I am a Catholic but I don’t like the Irish Catholics over here.”

He explains: “You go into a Protestant area, they give you tea and cake, they’re friendly. You go into a Catholic area, they throw… stones and they shoot at you. So, it’s only natural that you’re going to be biased.”

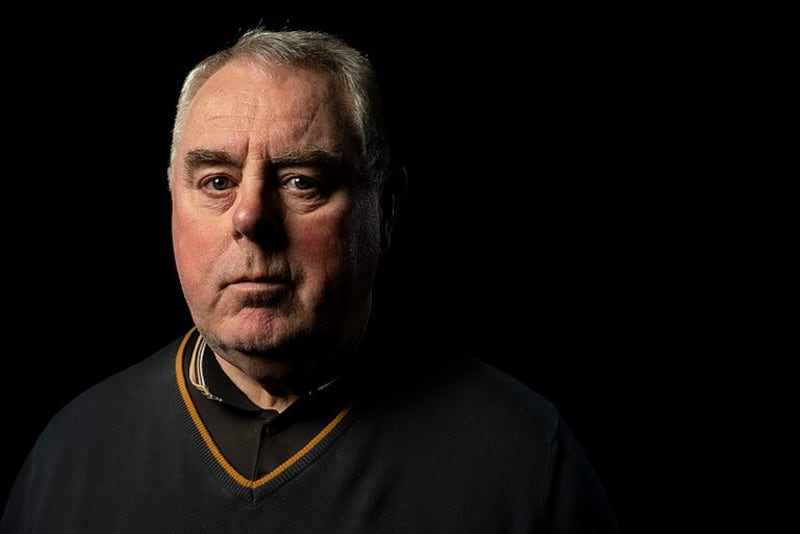

James, a former UDA member who regrets his actions, tells the familiar tale of how he was radicalised by Ian Paisley’s speech-making.

“He (Paisley) might have had a grain of truth and then a shovel full of s*** along with it. He was sowing fear.”

Episode one ends with a tense section as O’Rawe gives a sense of the IRA’s response in Belfast to events in Derry.

“It was snowing and there was four or five of us in a house when we heard about Bloody Sunday (pauses)… I’m going to leave it at that,” he says.

Asked why, he says, “Because… I don’t really want to talk about it. We were very, very angry… I’ve very vivid memories of it… it wasn’t too hard to say to yourselves, ‘you know what, I’m ready boys, let’s have it’.”