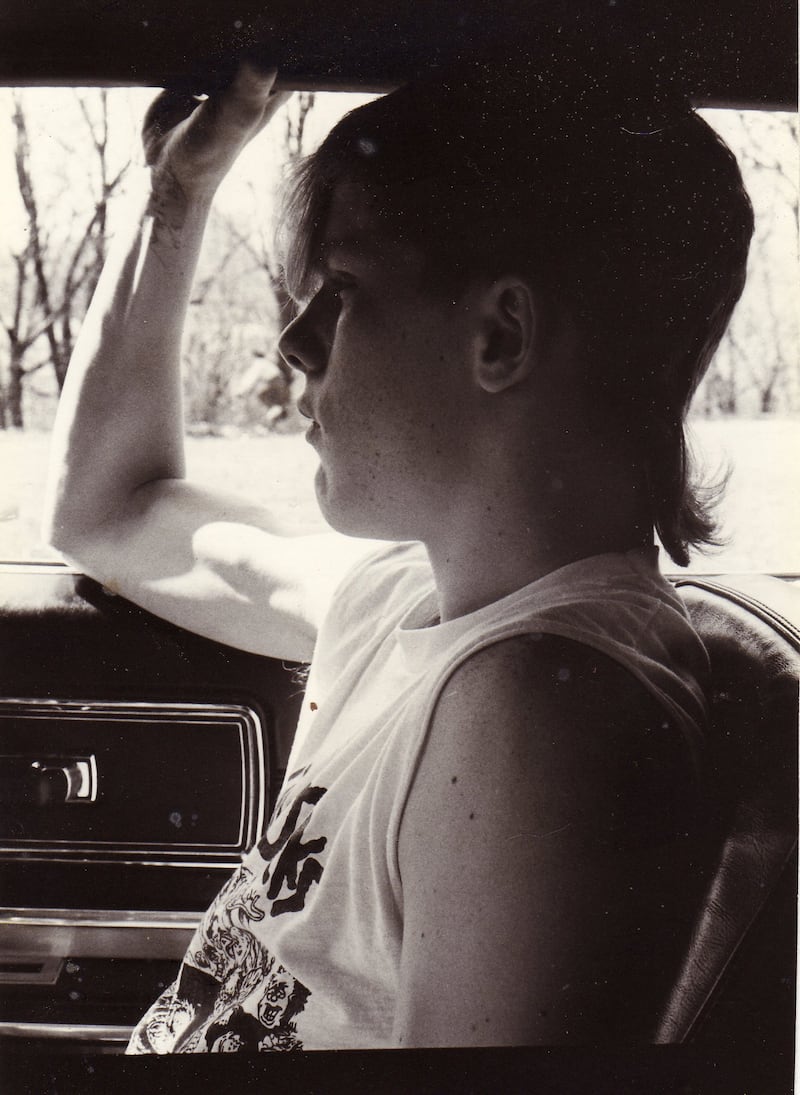

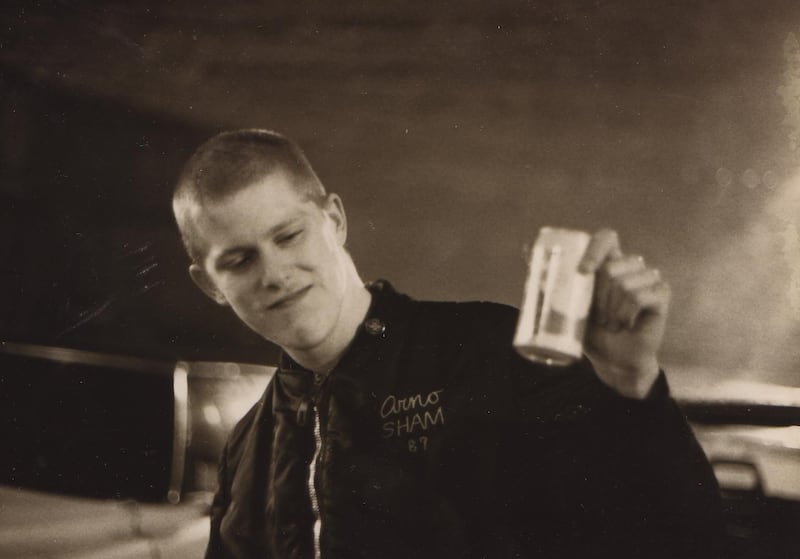

Arno Michaelis was 16 when he became a white power skinhead.

From schoolyard bully to white supremacist, Arno had long lived in the shadow of his inner rage, and already had little patience for fitting in.

“My entire life I’d been contrarian,” he said. “Whatever I saw in the status quo, I didn’t want to conform.”

To the teenage Arno, escaping the norm in 1980s Wisconsin meant rejecting multiculturalism, even where it clearly worked against his own interests.

Early on, he was listening to hip hop artists like Run DMC and Grandmaster Flash, attending concerts as one of a handful of local white kids interested in the burgeoning art form, and even formed a small break-dancing troupe with some friends.

But as the predominantly black artists gradually made their way into the cultural mainstream, he found freedom, instead, in the raucous chaos of punk.

Above all, punk was a refuge. His dad was an alcoholic, and his parents fought bitterly – so much so that the constant strain of having to find outlets away from family home became traumatic and lonely.

In spite of this, he views his childhood as largely “idyllic” – full of love, and cushioned from the excesses of city life in the quiet western edge of Lake Michigan.

“My family loved me very much,” he said. “More than they loved each other – but a lot of that stemmed from my dad’s alcoholism.

“Them fighting was really the only trauma I experienced as a child.”

Outside observers might not have picked him out for a future extremist: Arno’s family were neither poor nor rich; the violence he witnessed at home was emotional, rather than physical.

And yet it is this emotional trauma that Arno credits as the predominant reason he first entered the skinhead movement.

“To me punk was about smashing stuff, and that combination with the trauma I’d been through was how I interpreted punk and how I was empowered to be a white power skinhead,” he said.

“Trauma is a relative thing and when you’ve been through something that is traumatic, it’s not necessarily apparent to you.

“I was riding this thing about being a power for my people.”

His parents eventually split up when he was 18 (“18 years too late”, as Arno puts it), and his relationship with them both instantly started to improve.

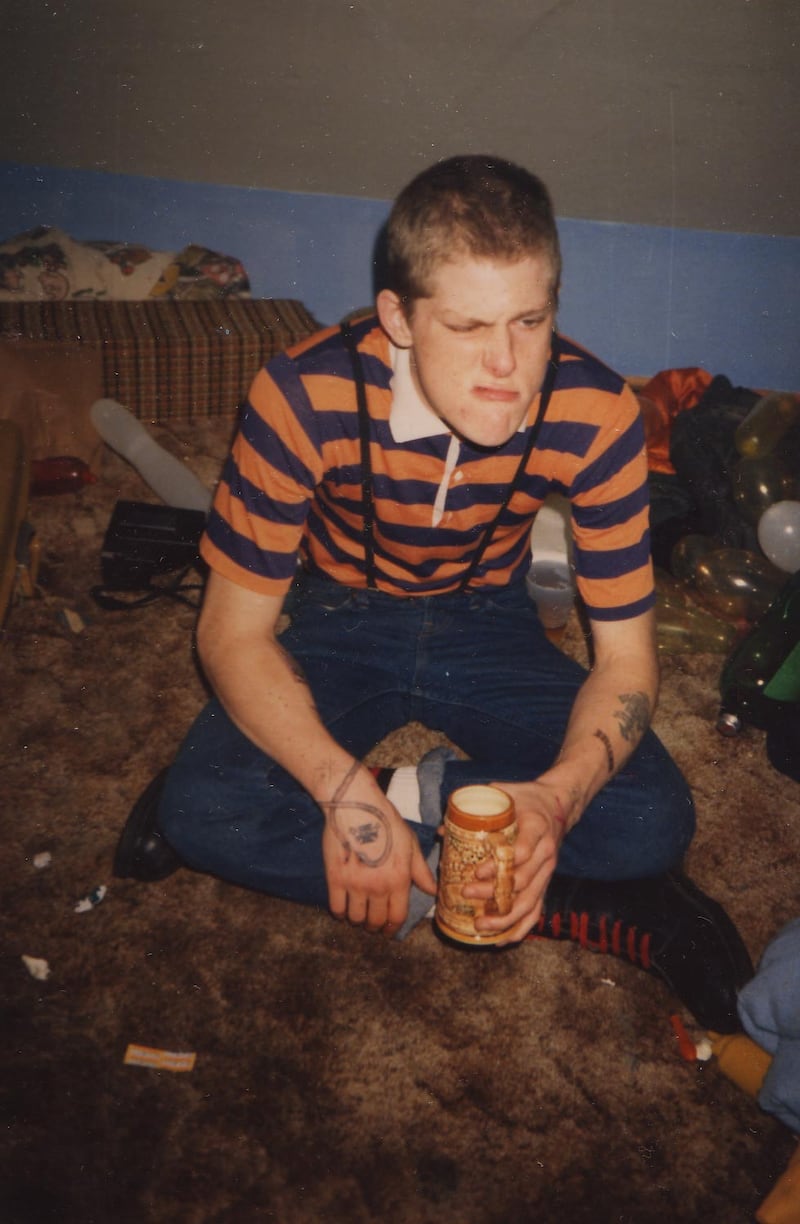

By that time, though, Arno’s interest in racially-driven music had already plunged him into a life of violence and petty crime.

“I just kind of became this ball of hate and violence, and the white power thing gave me a context for it,” he recalled.

“It said the reason why I’m angry, the reason why I’m irate, the reason why I’m violent is because of oppression.”

For Arno, being part of an oppressed white race explained his inner turmoil in a way that other outlets had not.

There were African American societies in college: Why not white societies? Black people had their own Black History Month: What about white history?

“You have to be really ignorant of history to feel that way,” he said, looking back.

“Questioning things like that ignores the fact we’ve had a white-dominant culture for the past 500 years.”

He was now at the heart of a white power organisation he co-founded with acquaintances in the local punk scene, and the lead singer of a white power metal band, Centurion.

He spent his evenings drinking and attacking black and ethnic minority citizens for sport – often beating them so badly he later asked the police to investigate if he’d killed anyone.

And yet Arno wasn’t blind to the many paradoxes that would later hasten his move away from his extreme views.

An avid football fan, Arno ignored the irony of week in, week out watching his team, the Green Bay Packers, whose black and white players fought alongside each other.

And he hid a passion for the hit NBC sitcom, Seinfeld, whose central character, Jerry Seinfeld, was one of America’s best-known and much-loved Jewish comic actors.

“Looking back,” Arno said, “I did have a deep inner knowledge that what I was doing was wrong but there are a lot of similarities between extreme ideologies and addiction.

“When you’re addicted to heroin you know it’s not a good thing, but all you can think of is getting high again.”

The feeling wasn’t alien to him. At 14, seven years before he was legally allowed to buy a beer, Arno, like his father, had found solace in drink.

He remained drunk for the next 20 years.

“I finally quit in 2004,” he said, “but up until then I was constantly drinking – and I’m sure that helped to maintain that ideology.”

His exact reasons for getting clean, however, were as complex as his reasons for turning to white supremacy in the first place.

One particularly sobering moment clattered onto his doorstep one evening when a younger member of the group turned up at his house chuckling, and carrying a 12 pack of beer.

The youngster, as Arno recalls, looked up to him as an older brother figure in the group, even imitating the way he spoke and looked.

“He had this big grin on his face and he started really laughing,” he said.

“I asked him what was so funny and he told me gleefully how he had seen a Mexican kid in an alley on his way over to me and he had kicked the kid in the stomach and left him writhing on the ground.

“I couldn’t really get past the fact that was a kid, but when I asked him about it, he just said, ‘yeah, but he’ll be an adult some day’.

“You can’t really keep making exceptions – you can’t say, this is the way it is, oh, unless it’s a little kid. So I doubled down on those beliefs, cracked a beer and we listened to white power music together.

“I felt sick by that, but we still went out and attacked people that night.”

This episode, like the small, but insidious embarrassments that came of secretly enjoying mainstream, integrated culture, was to form the basis of a crossroads for Arno’s association with the white power movement.

“For all the time that I was involved, I had this growing sense of exhaustion in trying to keep those beliefs,” Arno said.

“But what was most exhausting, what was more wearing than anything, was that people who I claimed to hate treated me with kindness: treated me as a human being, even when I was hostile to them.

“I would often run away from them – literally run to try to distance myself from them.”

Whether it was his kindly boss, who was Jewish, or his black and Hispanic colleagues, he simply couldn’t find a way to distance himself with any sincerity.

“They’d say things like: ‘yeah, yeah, we get it. You’re racist. Would you like a sandwich?’ and I’d have spent all my money drinking the night before, so I’d take it and walk to another part of the room.

“I was very good at masking it at the time and acting like it didn’t affect me, but as hard as I tried, it just made me all the more exhausted.”

Being open with his beliefs brought risks.

In a moment of spite, Arno decided to get a tattoo of a swastika on his middle finger – ideally placed for flipping off ethnic minorities in the street.

The symbol didn’t play so well with a grandmotherly woman of colour serving him in McDonald’s, with whom he had built a rapport over his payday lunch ritual: he desperately tried, and failed, to hide his hands as he paid for the food.

But the major catalysts for change were yet to come.

In 1990, a white teenager Arno helped indoctrinate in the movement was murdered in a street fight after turning to the group for protection against bullies in his predominantly black school.

Four years later, in 1994, a second friend was killed after attending a concert by Arno’s band.

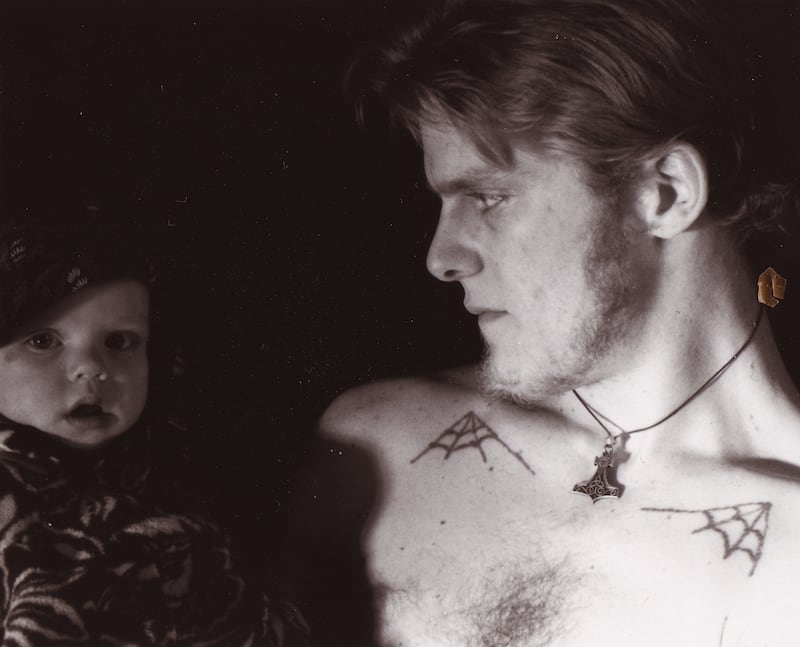

That was also the year he became a single parent for his two-year-old daughter, after her mother left town for Florida.

Arno was broken, lost and exhausted. He was 24 years old.

Two people who had kept their faith in him, however, were his parents.

“They refused to ever give up on me,” he said.

“They were both mortified by what I was doing, but they never said ‘that’s it’.”

They would go on to help him fight for custody of his daughter, hiring lawyers and ensuring their son didn’t lose the most stable – and most important – part of his life from the last few years.

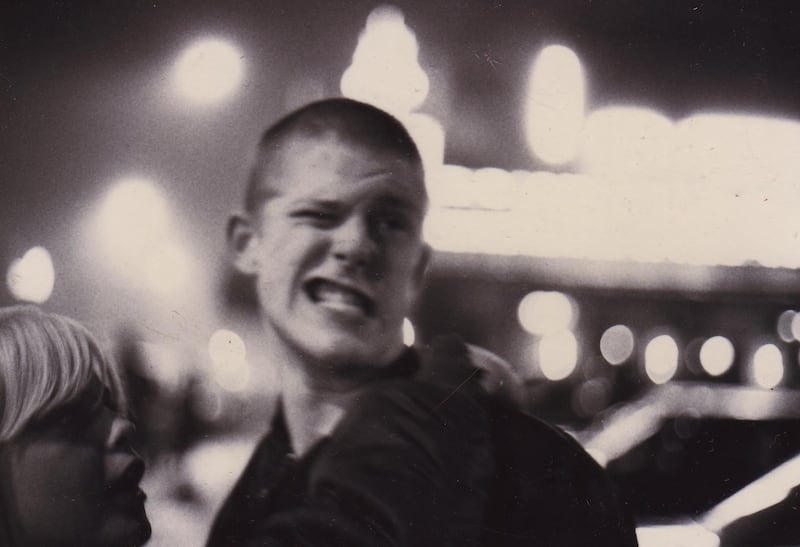

Finally, after the last Centurion gig that ended in another death, Arno knew he wanted out.

He and his bandmates, exhausted as they were, had been talking for some time about moving away from the skinhead movement to focus on creating mainstream music.

“We just wanted to be more of a regular metal band,” Arno said.

“We didn’t have aspirations to be Metallica or anything, we just wanted to play and we were doing just that, and hanging out with other metal bands – some of which had black and Latino members.

“Once we saw outside the box…”

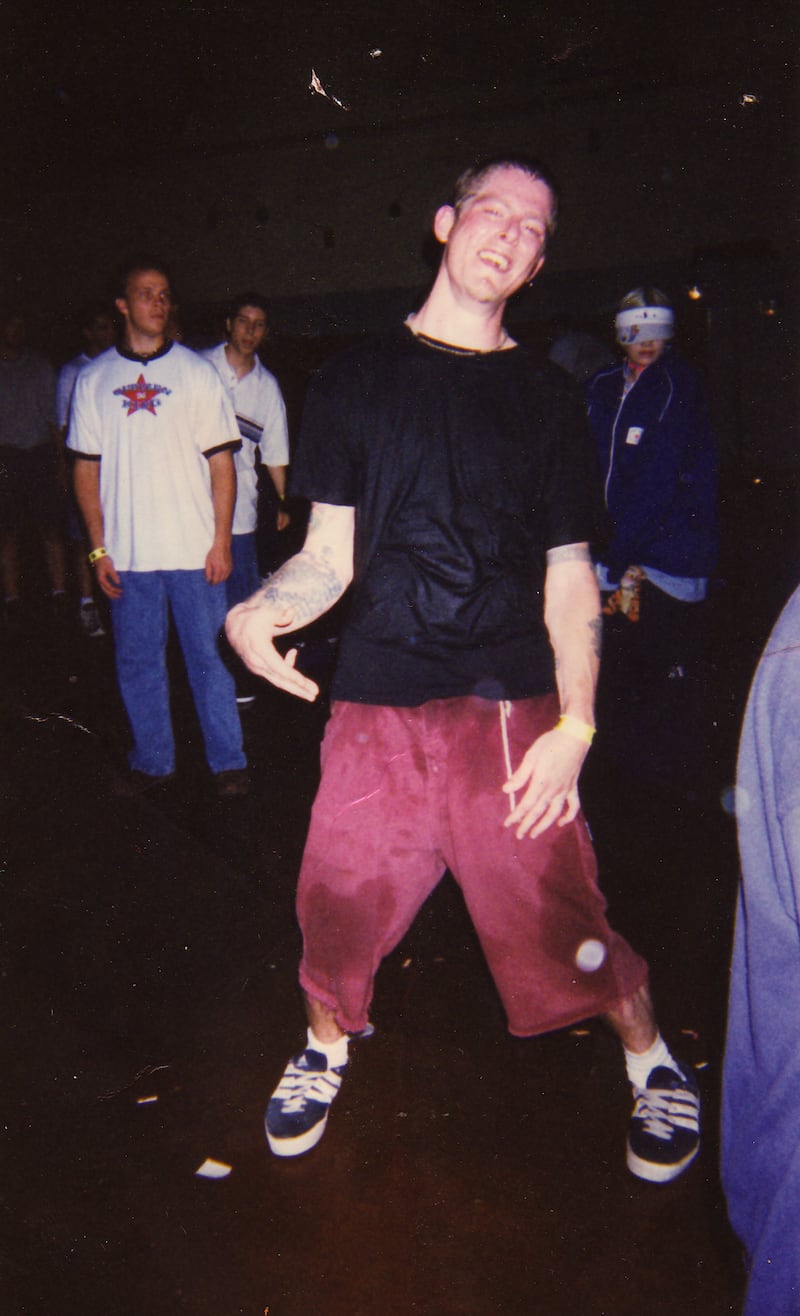

After eight years living the life of a white power skinhead, Arno Michaelis left the movement for good.

He continued to battle alcoholism for another 10 years, flinging himself into the Wisconsin rave scene with gusto.

He’d turn up at concerts, drinking heavily, with people who asked about his swastikas and foreboding white power tattoos, and proclaimed: “It doesn’t matter where you came from, what matters is who you are now.”

Eventually, the tattoos went too.

“Whenever somebody asks me how painful it was to have them done, I always tell them it’s way, way worse getting them removed,” he said, “Like someone literally burning your skin off with a laser.”

He was getting better, and yet, properly “cleaning the wound” of his past, as Arno calls it, would be more painful than anything he had experienced to that point.

In 2007, finally sober and without the numbing effects of alcohol to blunt his emotions, Arno went through another breakdown of a serious relationship.

Some time after this, he thought of writing a book about his experiences, and he eventually self-published his story: My Life After Hate.

It was 2010. And over the course of the next two years, the book pulled in a small, but influential readership in the world of humanitarian activism.

On August 5 2012, Wade Michael Page, a former US Army psychological operations specialist with a history of alcohol abuse, walked into a Sikh temple in Oak Creek, Wisconsin, and gunned down several members of the congregation, killing six and wounding four others, before turning his gun on himself.

Page was a white supremacist and had been noted as a member of several white power organisations, including holding links to the local Milwaukee skinhead and white power music scene that Arno Michaelis had been instrumental in creating. He was 40 years old, a year younger than Arno.

One of those who died in the massacre was the temple’s president, Satwant Singh Kaleka.

In the weeks that followed, amidst a raging debate on gun violence and a spike in race-related hate crime, Kaleka’s son, Pardeep, contacted Arno, whose autobiography had allowed him to secure the occasional speaking job in schools and colleges, away from his new life in IT.

Their meeting was to form a lasting friendship, and allow Arno to move full time into the world of anti-extremist activism.

Today, Pardeep and Arno are co-founders of Serve 2 Unite, an organisation centred around youth mentoring and resistance to hate, in an effort to drive vulnerable kids away from all forms of extremist ideology.

For Arno, this is one of the most important and significant outcomes of his redemption.

“The past 500 years of human existence have been shaped by white supremacy and shaped by racism, and until we as a society own up to that it can never be reconciled and we’re never going to keel over, never going to be able to move forward.

“My story and my personal work is not only about my personal reconciliation, but ours as a society as well.

“And I really believe that if you do it with compassion, and with forgiveness, and with love, they can be successfully done and we can come together as a human species and find a way to move forward.”

You can find out more about Arno’s story at mylifeafterhate.com.