Many reptiles such as skinks, spiny iguanas and different types of geckos detach their tails to escape the grasp of their predators.

The detached tail continues to wriggle, creating a false sense of struggle while distracting the predator at the same time.

Scientists have found this self-defence ability, known as autotomy or self-amputation, goes all the way back to lizard ancestors – a group of ancient reptiles who lived 289 million years ago.

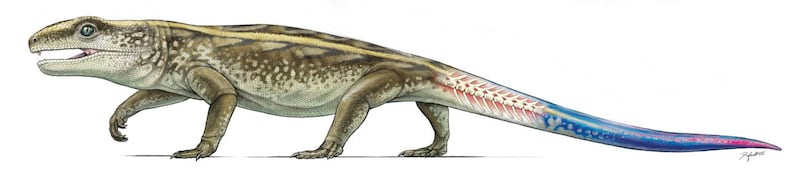

Much like the modern-day lizards, these reptiles, called captorhinus, avoided being preyed upon by larger meat-eating amphibians by getting rid of their tails.

Co-author Aaron LeBlanc, of the University of Toronto Mississauga, said: “One of the ways captorhinids could do this was by having breakable tail vertebrae.”

Professor Robert Reisz, also of the University of Toronto Mississauga, added: “If a predator grabbed hold of one of these reptiles, the vertebra would break at the crack and the tail would drop off, allowing the captorhinid to escape relatively unharmed.”

The team says that the mechanism works because there are “cracks” in the tail vertebrae of the lizards that act like perforated lines, allowing vertebrae to break in half along the planes of weakness.

Analysing more than 70 captorhinid skeletons, the team found that these so-called cracks are well-formed in younger species but tended to fuse up in some adults.

This makes sense, since predation is much greater on young individuals and they need this ability to defend themselves, the researchers said.

The study authors believe this escape strategy may have been key to their success as the captorhinus were the most common reptiles of their time.

According to the team, this trait disappeared when the species died out but re-evolved in lizards some 70 million years ago.

The study is published in the journal Scientific Reports.