Laboratory-grown “mini-placentas” created by British scientists could help prevent devastating lost pregnancies, scientists believe.

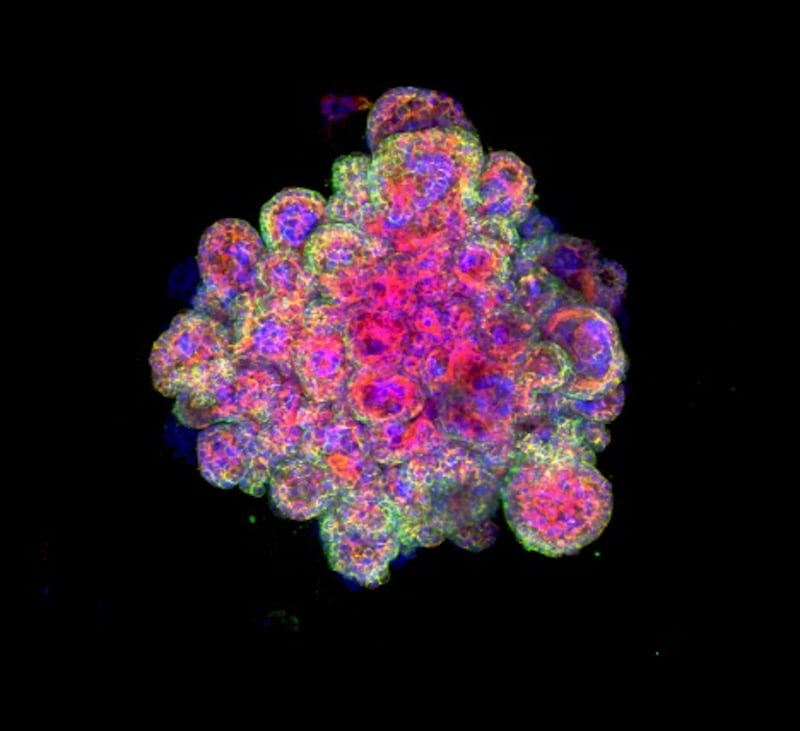

The “organoids” were developed at Cambridge University as a tool for unravelling some of the mysteries of early pregnancy.

In future they could unlock secrets that will help scientists tackle problems such as miscarriage, stillbirth and premature delivery.

The Cambridge team grew the organ models using cells from villi, tiny frond-like structures, taken from placental tissue.

In the laboratory the organoids organised themselves into multi-cellular structures capable of secreting the proteins and hormones that affect a mother’s metabolism during pregnancy.

Analysis showed they closely resembled normal placentas during the first month of pregnancy.

They were so much like the real thing they recorded a positive response when subjected to an over-the-counter pregnancy test.

Professor Graham Burton, director of Cambridge University’s Centre for Trophoblast Research, who was a member of the research team, said: “These ‘mini-placentas’ build on decades of research and we believe they will transform work in this field.

“They will play an important role in helping us investigate events that happen during the earliest stages of pregnancy and yet have profound consequences for the lifelong health of the mother and her offspring.

“The placenta supplies all the oxygen and nutrients essential for growth of the foetus, and if it fails to develop properly the pregnancy can sadly end with a low birthweight baby or even a stillbirth.”

Many pregnancies fail because the embryo does not attach itself correctly to the lining of the womb.

But little is understood about this critical early stage of pregnancy, said the scientists writing in the journal Nature.

Animals are too dissimilar to humans to provide useful models of placental development and implantation.

The new placenta model joins a range of other organoids being used in research including “mini-livers”, “mini-lungs” and even “mini-brains”.

Last year, the same team reported growing miniature functional models of the womb lining.

Lead author Dr Margherita Turco said: “The placenta is absolutely essential for supporting the baby as it grows inside the mother.

“When it doesn’t function properly, it can result in serious problems, from pre-eclampsia to miscarriage, with immediate and lifelong consequences for both mother and child. But our knowledge of this important organ is very limited because of a lack of good experimental models.”

The organoids may answer unresolved questions about relationships between the placenta, the womb and the foetus, said the scientists.

For instance, experts do not know why the placenta prevents some infections passing from mother to baby while allowing others, such as the zika virus, through.

The mini-placentas could also be used to check the safety of new drugs taken during early pregnancy, and shed light on how chromosomal abnormalities can upset a baby’s normal development.

Further in the future they may also provide stem cell therapies for failing pregnancies, the researchers said.