But mum, it’s not my fault – biology made me do it.

The terrible teens are not just a human phenomenon, and are not necessarily a bad thing, scientists say.

Researchers say impulsiveness in adolescence is not just a phase, with human brains and the brains of other primates going through very similar changes, particularly in the areas that affect self-control.

Co-author Christos Constantinidis of Wake Forest School of Medicine, said: “The monkey is really the most powerful animal model that comes closest to the human condition.

“They have a developed prefrontal cortex and follow a similar trajectory with the same patterns of maturation between adolescence and adulthood.”

Structural, functional, and neurophysiological comparisons between humans and macaque monkeys show the difficulty in stopping reactive responses is similar in our primate counterparts.

The monkeys also showed limitations in tests where they have to stop a reactive response during puberty.

Co-author of the study, Beatriz Luna of the University of Pittsburgh, said: “As is widely known, adolescence is a time of heightened impulsivity and sensation seeking, leading to questionable choices.

“However, this behavioural tendency is based on an adaptive neurobiological process that is crucial for moulding the brain based on gaining new experiences.”

Scientists say that taking risks and having thrilling adventures has its benefits.

Prof Luna added: “You don’t have this perfect inhibitory control system in adolescence, but that’s happening for a reason.

“It has survived evolution because it’s actually allowing for new experiences to provide information about the environment that is critical for optimal specialisation of the brain to occur.

“Understanding the neural mechanisms that underlie this transitional period in our primate counterparts is critical to informing us about this period of brain and cognitive maturation.”

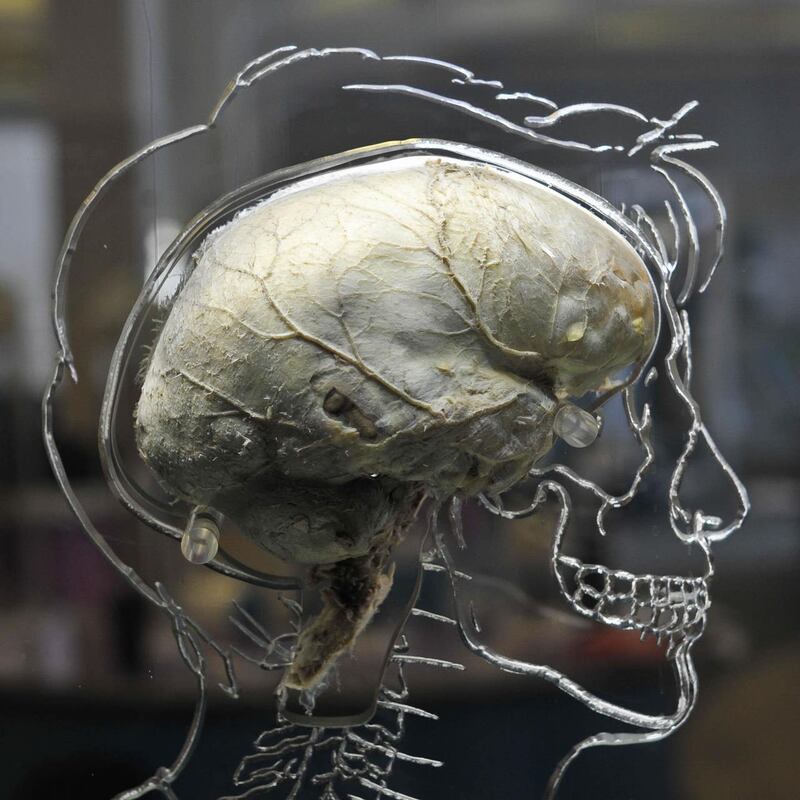

During adolescence human neurological development is characterised by changes in structural anatomy.

Specifically, by this time all foundational aspects of brain organisation are in place and during this time they undergo refinements that will enable the most optimal way to operate to deal with the demands of their specific environment.

The scientists say development of neural activity patterns that allow for the preparation of a response seems to be a key element of this phase of development, and essential to successful performance on self-control tasks.

This suggests that self-control is not just about the ability, in the moment, to inhibit a behaviour, says the study published in the Trends in Neurosciences journal.

Professor Constantinidis said: “Executive function involves not only reflexive responses but actually being prepared ahead of time to create an appropriate plan.

“This is the change between the adolescent and adult brain and it is strikingly clear both in the human data and in the animal data.

“It is important for there to be a period where the animal or the human is actively encouraged to explore because gaining these new experiences will help mould what the adult trajectories are going to be,” Prof Luna concludes.